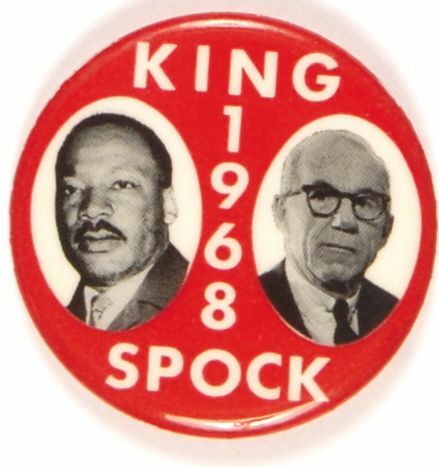

While a historic political button suggests that the late Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. once ran for president with pediatrician and author Dr. Benjamin Spock, the two never officially declared their candidacy. Anti-Vietnam War activists made the button to suggest the idea that King and Spock run in the 1968 presidential election as third party candidates to oppose military interventionism and promote democratic socialism. King reportedly considered a presidential bid.

A group of liberal activists — Yale chaplain and activist William Sloan Coffin, professor Allard Lowenstein, and socialist Norman Thomas — lobbied King and Spock to run. Thomas himself ran for president six times as a socialist and was later a co-founder of the ACLU. Lowenstein graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and from Yale University, was an anti-war activist, and taught at Stanford University and at North Carolina State University.

The three launched a campaign to promote the King/Spock ticket for the 1968 election against then-incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson. Under pressure at home over the Vietnam War, Johnson eventually withdrew his name for re-election and Democrats nominated Hubert Humphrey, who was defeated by Republican former Vice President Richard Nixon.

King and Spock had a relationship built through activism and protest during the 1960’s. Spock used his fame from his popular book, Dr. Spock’s Baby and Childcare, to oppose the Vietnam War and nuclear proliferation. King’s wife, Coretta Scott King, marched with him in Washington, D.C., in 1965. According to her book, she pressure her husband to oppose the war, arguing that “he could become the most important symbol for peace in this country, as well as for world peace.”

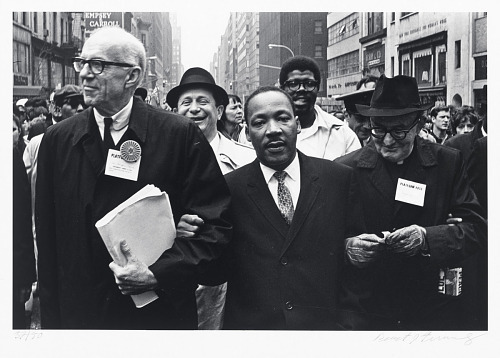

Martin Luther King marched in his first anti-war demonstration in March 1967, alongside Spock.

King later delivered a sermon against the war at Riverside Church, and used that address, “Beyond Vietnam,” to build a protest campaign with Spock and grassroots organizations across the county ahead of the 1968 presidential elections. The campaign, called “Vietnam Summer,” mobilized anti-war demonstrators who canvassed door-to-door, counseled young men on how to avoid the draft, disseminated anti-war literature, and held “teach-ins” on college campuses to attracting media attention and push policy goals among the students.

In January 1968, Spock, Coffin, and three others were indicted for conspiring to violate the draft laws. King submitted a statement of support to the court on their behalf. Spock was tried and found guilty, but the verdict was overturned on appeal.

Thomas, whom King once called “the bravest man I ever met,” died in December of 1968, just after the election. Coffin went on to spend decades in academia writing on nuclear disarmament, and died in 2006 at the age of 81. In 1980, Lowenstein was murdered in his law office by a mentally ill former student who had worked with him during the civil rights movement.

Spock continued to demonstrate for unionization and other issues. He ran for president in 1972 as a third-party candidate from “The People’s Party,” a political party formed by groups of the “peace movement” in the 1960’s. His platform included free medical care, legalized abortion, legalized marijuana, a guaranteed minimum wage, and the withdrawal of American troops from all foreign countries. Spock finished last in that race, winning 78,759 votes, or .10%, behind incumbent President Richard Nixon and Democrat nominee George McGovern.

King never sought political office. He often expressed that government intervention should be downstream from public opinion and culture, but UCLA’s 2015 release of audio archives from a 1965 King speech at the university shows his view on the role of legislation.

“It may be true that you can’t legislate integration, but you can legislate desegregation. It may be true that morality cannot be legislated, but behavior can be regulated,” said King in 1965. “It may be true that the law cannot change the heart, but it can restrain the heartless. It may be true that the law can’t make a man love me, but it can restrain him from lynching me, and I think that’s pretty important also. So while the law may not change the hearts of men, it does change the habits of men. And when you change the habits of men, pretty soon the attitudes and the hearts will be changed. And so there is a need for strong legislation constantly to grapple with the problems we face.”

King was assassinated by James Earl Ray on April 4, 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee.