At times, state law has granted pay raises to some classes of employees after they’ve been in a job for a certain amount of time. Can the General Assembly abolish such automatic raises proactively? The answer, according to the state’s second highest court, is “yes.”

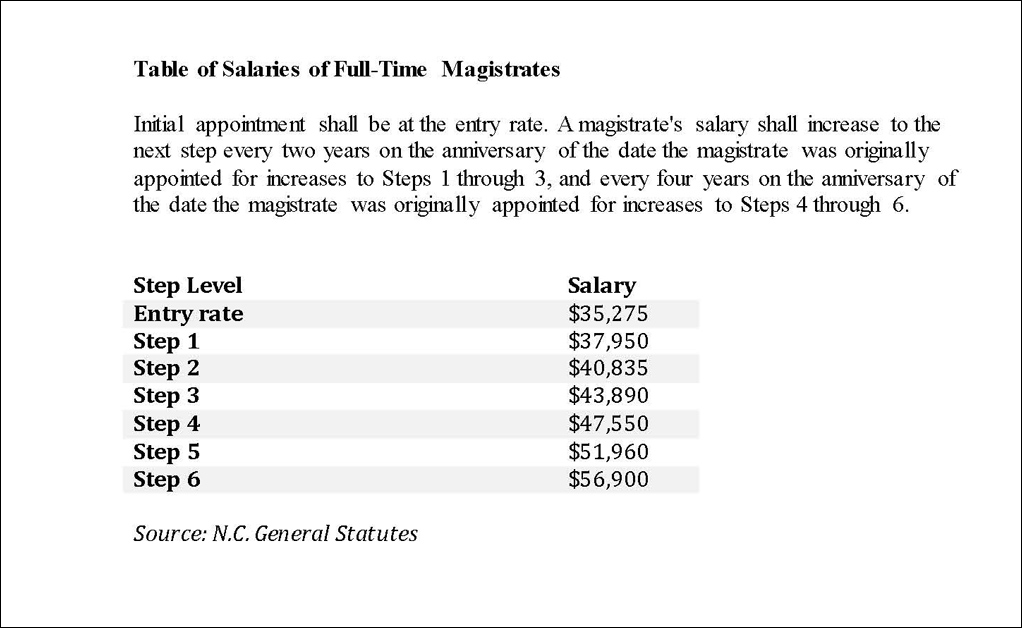

Magistrates’ pay is defined by statute. Under the compensation scheme created by the General Assembly, there’s a beginning pay grade. Beyond that are six higher pay levels — known as “steps” — which magistrates reach when they have spent a set amount of time at the previous level (see chart). In 2009, during the depths of the Great Recession, the General Assembly suspended step pay promotions; they were restarted as of July 1, 2014. Just before the step pay increases resumed, a group of magistrates filled a class-action lawsuit against the state. The magistrates claimed that the pay increase schedule in the statute amounted to a vested contractual right and that the state had breached this contract when it suspended the step pay increases.

A Superior Court held that the statute did not create any such contractual rights and dismissed the lawsuit. The magistrates then brought their claim to the Court of Appeals.

Are magistrates like teachers?

Like the lower court, the appeals court was not persuaded that magistrates had a right to automatic step pay increases.

“In the present case, we hold that plaintiffs failed to meet their burden of showing that the Salary Statute creates a binding contract right for magistrates to receive a certain salary in the future for work performed in the future,” wrote Judge Chris Dillon for the court. (Emphasis in decision.)

“Rather, the General Assembly is free to amend the Salary Statute so long as, in doing so, the General Assembly does not reduce a magistrate’s salary for work already performed.”

Before the appeals court, a key precedent was the N.C. Supreme Court’s recent holding in N.C. Ass’n. of Educators, the teacher tenure case. In that case, the high court held that:

Construing a statute to create contractual rights in the absence of an expression of unequivocal intent would be at best ill-advised, binding the hands of future sessions of the legislature and obstructing or preventing subsequent revisions and repeals. We are deeply reluctant to limit drastically the essential powers of a legislative body by finding a contract created by statute without compelling supporting evidence.

The N.C. Supreme Court rejected the legislature’s attempt to remove enhanced job protections from teachers who already had obtained career status. The high court concluded that those teachers had entered into contacts with local school districts including the promise of tenure, not because the wording of the state statute created an enforceable future contract.

The Supreme Court left undisturbed the Court of Appeals’ determination that the General Assembly could eliminate the prospect of tenure for teachers who hadn’t spent enough time on the job to achieve career status.

“The magistrates here are much like the teachers in N.C. Ass’n. of Educators who had not yet worked the requisite number of years to have a contractual right to career status,” wrote Dillon.

“Here, a magistrate could not have a contractual right to receive a higher salary in a future year simply until the magistrate completed work in that future year. The actions of the General Assembly in suspending step increases for future work did not take away any benefit already earned by plaintiffs, whereas in N.C. Ass’n of Educators, the successful plaintiffs had already worked the requisite years to earn career status.”

Court of Appeals decisions are binding interpretations of state law unless overruled by the state Supreme Court. As the decision by the three-judge panel of the appeals court was unanimous, the high court is not required to hear the case if the magistrates seek an appeal.

The case is Adams v. State of NC (15-1275).