A senior state lawmaker who heads a committee overseeing the state Medicaid program says a newly released audit outlining systemic management mistakes gives an additional reason to oppose Gov. Roy Cooper’s proposal to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act.

State Rep. Craig Horn, R-Union, co-chairs a committee that has examined Medicaid waste, fraud, and abuse. He said he was disturbed by the audit, which found that high error rates in determining Medicaid eligibility led to some applicants not receiving needed services while others who weren’t entitled to receive benefits got them.

Cooper has asked the Obama administration to expand Medicaid to as many as 650,000 people at a cost to the state of up to $6 billion over 10 years.

“We’re all sick and tired of hearing about fraud, waste, and abuse,” said Horn, whose Joint Legislative Program Evaluation Oversight Committee heard testimony in November on another troubling report released by the state Program Evaluation Division.

“Do I sense an appetite in the legislature given the PED report, given these other reports, for us to consider Medicaid expansion in any broad sense? Absolutely not,” Horn said. He did not rule out adding to the Medicaid rolls a smaller, targeted population of disabled individuals who might have slipped through eligibility cracks.

The PED report concluded that the state’s Medicaid program is not detecting or preventing waste, fraud, and abuse due to inadequate staffing, bureaucratic cooperation, and documentation. It said the Medicaid Program Integrity Section is paying outside contractors much more to root out those problems than they return in savings.

Similar findings were disclosed in another audit from the State Auditor released in April. Of 396 Medicaid cases reviewed by auditors, 13 percent contained overpayments. Projected across the entire Medicaid population, “the likely total errors are $835 million,” that audit stated.

“It’s time for us to call people out, set deadlines, and create a scenario where there must be a penalty for failure,” Horn said. “There can’t just be a reward for progress. There’s got to be a penalty for failure or else you’re going to get mediocrity, and it appears to me we’ve got mediocrity.”

This performance audit released Thursday listed results from 10 counties that were reviewed between July 1, 2015, and June 30, 2016. The Office of the State Auditor contracted with outside experts to perform tests of the county Medicaid eligibility approval systems, and those findings were verified by state auditors.

“Most of the 10 sample county departments of social services did not consistently provide adequate oversight or controls for the eligibility determination of new applications and recertifications,” the audit said. Nor did DHHS provide adequate oversight or controls for those matters.

“As a result, auditors discovered higher than expected error rates in accuracy and timeliness in several sample counties,” the audit said.

“Medicaid applicants likely received benefits for which they were not eligible,” the audit said. “Conversely, other Medicaid applicants were likely denied benefits for which they were eligible,” and might not have received medical services at the time they were needed because of delays in eligibility determination.

Medicaid is a state-administered program for 1.9 million children, poor, aged, and disabled people in North Carolina. County departments of social services determine financial eligibility for the program. Counties receive 75 percent reimbursement from the federal government for that work.

“During early phases of this audit, the department questioned its responsibility for program administration by repeatedly stressing that counties determine Medicaid eligibility, not the state, despite the state’s responsibility as specified in federal regulations and the State Medicaid Plan,” the audit said.

“The dance goes on,” Horn said of the finger-pointing. “The state is ultimately responsible. We can delegate authority, but we cannot delegate responsibility. That is a fundamental precept of all management.”

The audit suggested that the General Assembly should clarify the DHHS role “as the established authority to oversee and administer” the state’s Medicaid program, possibly by changing the state statute to say DHHS “has the ultimate responsibility for the accurate and timely determination of eligibility for participants in the Medicaid program.”

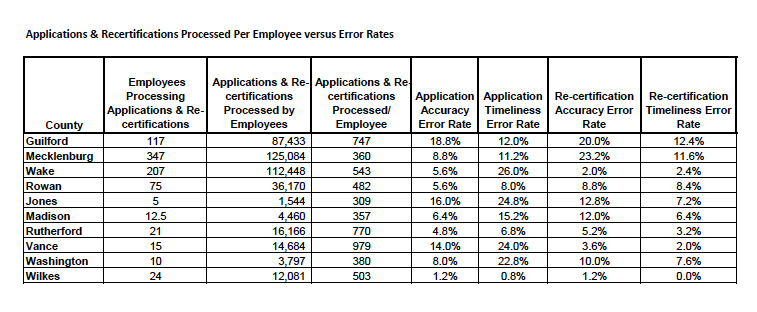

The audit included the urban counties of Guilford, Mecklenburg, and Wake; Rowan, a mid-sized, suburban county; and the small, rural counties of Jones, Madison, Rutherford, Vance, Washington, and Wilkes.

Error rates among the counties ranged from 1.2 percent in Wilkes to 18.8 percent in Guilford for accuracy of new applications; 0.8 percent in Wilkes to 26 percent in Wake for timeliness in new application determinations; 1.2 percent in Wilkes to 23.2 percent in Mecklenburg for recertification accuracy; and 0.0 percent in Wilkes to 12.4 percent in Guilford for recertification timeliness.

The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services sets the error rate threshold at 3 percent. Rates above that subject a state to potential penalties including loss of some federal Medicaid funds.

Because each county processes Medicaid applications differently, auditors could not project error rates across the other 90 counties.

The most common errors found in the audit were caused by typographical mistakes, inaccurate recording, and lack of necessary documentation in case files to verify income and assets to determine eligibility.

County social services departments consistently blamed inadequate staffing, staff turnover, lack of training on the state’s NC FAST computer system for processing Medicaid applications, and a crush of applications under Obamacare. They all said they were implementing various training and quality assurance initiatives to reduce errors.

As a partial response to the audit, in February DHHS will initiate a county-level quality control plan.