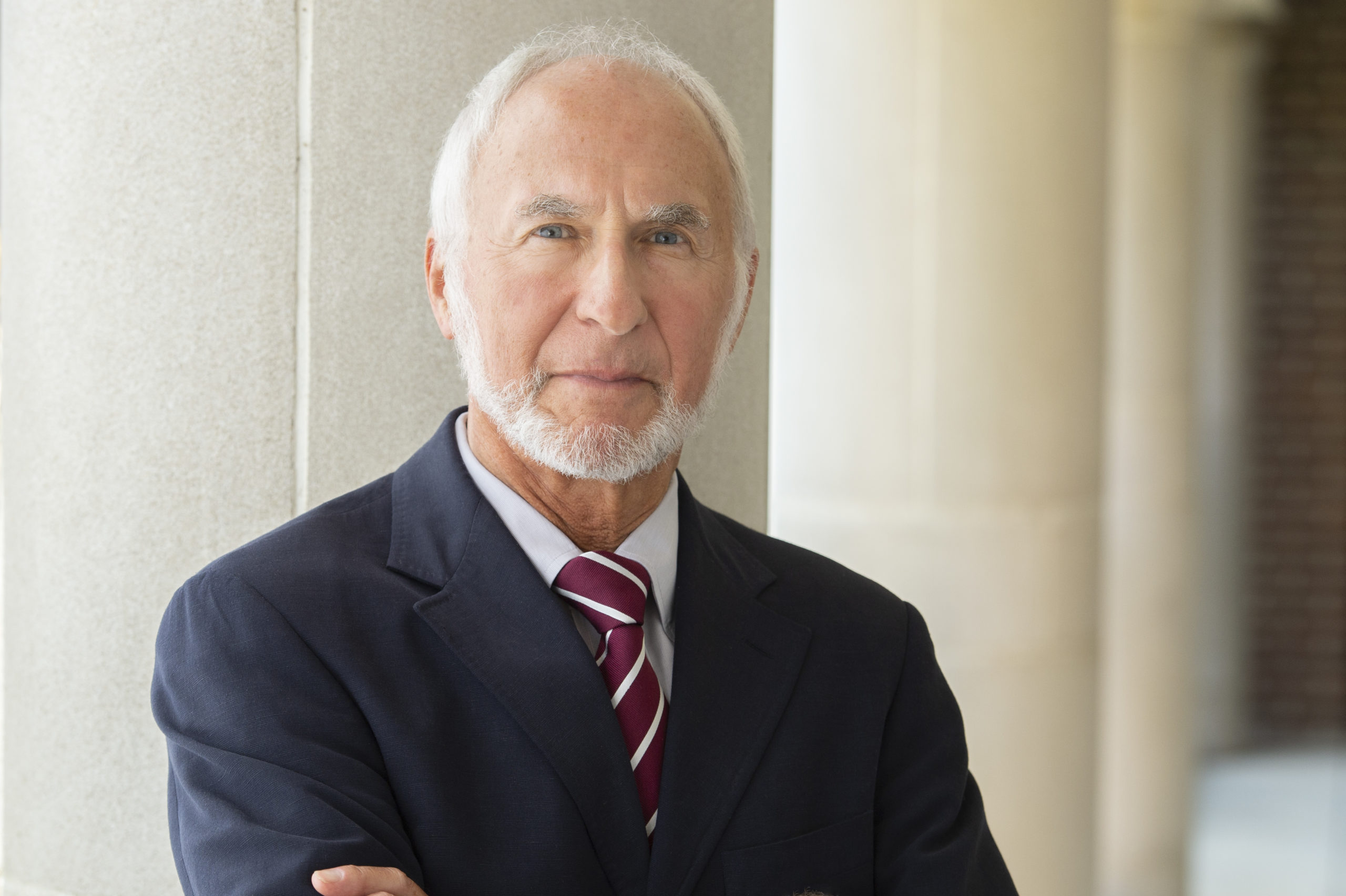

A retired UNC law school constitutional expert says forced removal of Supreme Court justices from consideration of a case would be “particularly dangerous.”

John Orth, William Rand Kenan Jr. professor of law emeritus, makes that argument in a friend-of-the-court brief filed Friday morning in the case of NC NAACP v. Moore. The state Supreme Court is considering the plaintiff’s motion to remove two Republican justices from participating in the case.

“Involuntary recusal” is the legal term tied to the attempt to remove the two justices against their will. Orth’s brief explains why he “believes that involuntary recusal would violate the Constitution of North Carolina.”

“Any constitutional violation would be dangerous,” Orth writes. “Involuntary recusal would be particularly dangerous. As an interpretation of the North Carolina Constitution by the Supreme Court of North Carolina, it is unclear how it could be reviewed and corrected. And it would set a precedent pregnant of many harms.”

Orth’s brief examines the constitutionality of the NC NAACP’s motion to the seven-member state Supreme Court requesting that they force the recusal of the court’s two newest Republican justices from hearing the case challenging voters’ approval of two constitutional amendments. One amendment would require voter ID in North Carolina. The other would lower the state cap on income tax rates.

Justice Tamara Barringer is targeted for removal because she served as a state senator from Wake County when the General Assembly voted to place the constitutional amendments on the ballot in 2018. Justice Phil Berger Jr. is targeted because he is the son of Senate Leader Phil Berger, whose position is named as a defendant in the case.

Justice Anita Earls, a Democrat, has not been singled out for recusal despite having been the plaintiff’s attorney in related legislation targeting the Republican-led General Assembly.

Orth is a legal historian with 43 years of experience on the UNC law school faculty. “He is the author of numerous books and scholarly articles and has devoted a substantial portion of his career to the study of the North Carolina Constitution,” his brief explains. Among his six books is “the North Carolina treatise in the Oxford Commentaries on the State Constitutions of the United States series.”

Orth “has a strong professional and scholarly interest in the proper interpretation of the state constitution, specifically including the provisions at issue in this case.”

Recusal refers to a judge or justice’s voluntary decision not to participate in a particular case, Orth explains. “Involuntary recusal would constitute the temporary removal of a Justice from active service,” he adds. “As such, it violates the constitutional integrity of the judicial system and interferes with the separation of powers between the judicial and legislative branches of government.”

Involuntary recusal goes against two basic elements of the N.C. Constitution. The first sets the number of state Supreme Court justices at seven. The second explains that voters elect those justices.

“Involuntary recusal would unconstitutionally reduce the number of Justices deciding a particular case and interrupt their terms of service in violation of Article IV, [Sections] 6 and 16,” Orth writes.

Removal of Supreme Court justices is a job for the General Assembly, Orth writes. Legislators can remove justices through “impeachment or address.”

Thanks to a state constitutional amendment adopted in 1972, North Carolina also has a Judicial Standards Commission. That group can remove justices for “mental or physical incapacity,” “willful misconduct in office,” or “conduct prejudicial to the administration of justice,” Orth writes.

Because of the two existing procedures for removing justices, “Removal of a Justice by act of the Supreme Court would violate Article IV, [Section] 17,” Orth writes.

Each branch of state government ultimately derives its power from the people, as set out in the N.C. Constitution, Orth explains. “Removal of a Justice by the Supreme Court would exceed the power conferred on the Court by the Constitution and violate the fundamental principle of separation of powers prescribed by the Constitution.”

The case was pulled from the high court’s calendar back in September, but it has not been rescheduled.

Lawyers for both sides in the case were scheduled to submit briefs by Oct. 28. The briefs would have answered the Supreme Court’s questions about involuntary recusal of justices.

A motion filed Friday seeks to have the deadline for briefs extended to Nov. 4.