Who is Doug Heyl?

Members of a special legislative committee looking into the Atlantic Coast Pipeline would like to know. Heyl is a top communications official in the state Department of Environmental Quality.

But what role did Heyl play in the pipeline permitting process?

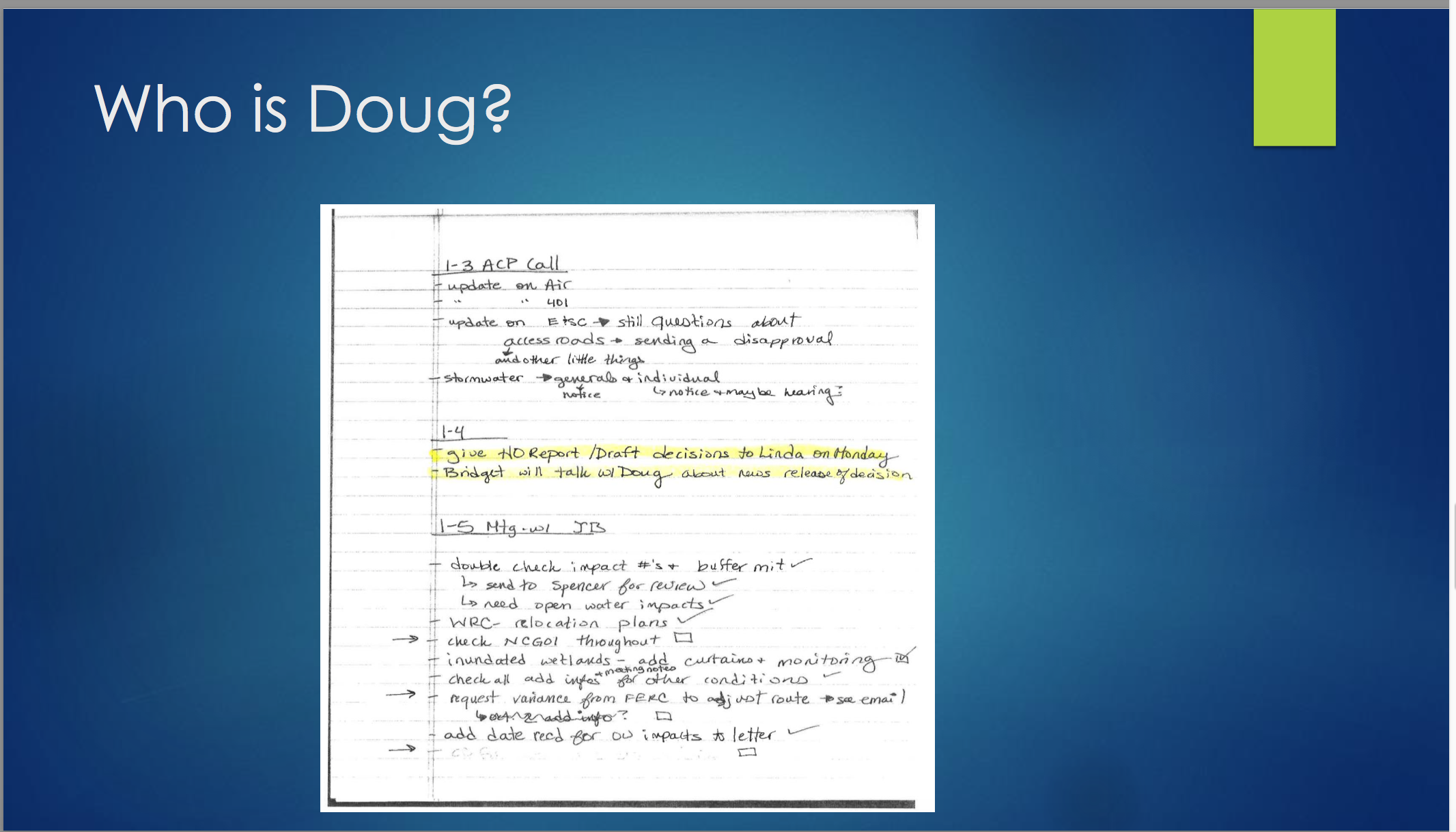

Sen. Paul Newton, R-Cabarrus, flashed a PowerPoint presentation during a meeting of the subcommittee Nov. 14. Slide No. 7 got people’s attention. It posed a simple question: Who is Doug?

Newton referred to a document, from the ACP permit file, showing handwritten meeting notes from Jan. 4: “give HO report to Linda on Monday. Bridget will talk w/Doug about news release of decision.” HO refers to hearing officer Brian Wrenn. “Bridget” is Bridget Munger, DEQ public information and communications specialist.

“Doug” is Doug Heyl.

Gov. Roy Cooper announced the mitigation fund — and DEQ announced the pipeline’s approval — roughly three weeks after the Jan. 4 meeting.

Carolina Journal has learned Heyl, 56, spent about 30 years as a Georgia-based political consultant for Democrats before taking a full-time job Oct. 16, 2017, as a DEQ deputy secretary.

CJ asked DEQ: Who is Doug Heyl, and what’s his role in the ACP?

“Doug had no role in the ACP permit process outside reviewing the external communications issued around the permit,” DEQ spokeswoman Megan Thorpe told CJ.

“Doug had no role in the MOU.”

We asked to speak with Heyl but were told he was busy and unavailable.

Heyl’s experience in state government — in state communications, particularly — is nebulous. CJ failed to find a profile page from Heyl on LinkedIn, a social media networking site ubiquitous among professionals and influencers. He has a Facebook page, but we found little about him on Twitter.

A state employee database lists Heyl as a deputy secretary in the DEQ, Newton noted. But Heyl isn’t listed on the DEQ website as a member of the leadership team or the communications office. Mysteries surrounding Heyl and the enigmatic nature of his employment raises the question of whether the DEQ role is nothing more than a warm place for Heyl to land before leaving to help Gov. Roy Cooper win re-election.

“We know he makes almost $114,000 a year in salary,” Newton said. “So, it appears that Mr. Heyl is now a deputy secretary in DEQ, with unknown job responsibilities, other than the fact the issuance of the ACP water quality permit had to be coordinated through him. Is this innocuous or nefarious? We don’t know, but need to know.”

On Oct. 15, Heyl’s position with the DEQ was reclassified from non-permanent to permanent.

Heyl lived in Stockbridge, Georgia, a suburb of Atlanta, and did business under the name of Scout Communications and All Points Communications. He was also affiliated with the Washington, D.C.-based Columbia Campaign Group. In August, nearly a year after he was hired at DEQ, he sold his Georgia home and bought a home in Garner.

CJ asked DEQ what led to his employment with the state. “Doug and his family were looking to move to North Carolina, and he sought out a job in the administration,” Thorpe told us.

The broader goal of the investigatory subcommittee is determining whether state approval of the North Carolina segment depended on Cooper’s administration securing a $57.8 million discretionary “mitigation” fund with the pipeline operators. Cooper’s office negotiated the fund and was established through a Memorandum of Understanding.

The state announced the pipeline fund in January. Soon after the announcement, Republican leaders cried foul. They said it appeared to be part of a “pay to play” scheme tied to the environmental permit ACP hoped to obtain from the governor’s administration.

Republican leaders said the deal was illegal. The N.C. Constitution gives the legislative branch the sole power to collect and appropriate money.

Cooper’s chief of staff, Kristi Jones, has told legislators the “mitigation fund was established independently of the DEQ permitting process.”

Lawmakers have sought answers from Cooper about the arrangement, but they haven’t been satisfied with the responses. Cooper and his office, as is usual, has failed to respond to questions from CJ.

The ACP is an underground natural gas transmission pipeline originating in West Virginia, traveling through Virginia, and ending in Robeson County. The project is a partnership among Richmond, Virginia-based Dominion Energy; Duke Energy; Piedmont Natural Gas; and Southern Company Gas. Gas from the ACP will supplement existing gas resources and fuel new electricity generation plants.

Dominion announced Friday it was temporarily suspending construction of the entire pipeline. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service asked for the stoppage after finding potential environmental problems not covered by earlier federal permits. The 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals granted a temporary stay, and Dominion voluntarily stopped work, the company said, until it gets more clarity from the court.

The money from the MOU funds originally was designated to mitigating all damage caused by the pipeline, economic development opportunities, and developing renewable energy projects.

Lawmakers stepped in.

In February, the General Assembly voted to direct the $57.8 million to the school systems in the eight counties along the ACP route. So far, North Carolina has seen none of that money.

Cooper’s office said the legislative action was politically motivated.

“Legislative Republicans have set a new low for partisan hypocrisy this week,” Cooper spokesman Ford Porter said. “Nearly every Republican legislator claims to support the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, yet they wanted to stop counties in its path from getting resources to ensure this project is a success.”

On Nov. 14, the subcommittee voted to hire a special outside investigator to get answers from Cooper’s office and the DEQ. The ACP committee is scheduled to meet 1 p.m. Wednesday.

Whether the committee will return to Heyl isn’t known. But the questions about him remain.

In 1988, Heyl worked for Missouri U.S. Rep. Dick Gephardt, who lost in that year’s Democratic presidential primary.

Heyl joined Bill Clinton’s campaign for president in 1991 and eventually became the Southern political director. In 1994, Heyl served as executive director of the Tennessee Democratic Party. Heyl managed James McGreevey’s 1997 campaign for governor of New Jersey. In 1998, Heyl was campaign manager for Florida Lt. Gov. Buddy MacKay in his race against Jeb Bush for governor. In 2000, Heyl worked for the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee.

In 2001, Heyl managed Glenn Cunningham’s campaign for mayor of Jersey City, New Jersey. Heyl managed Mark Taylor’s 2002 campaign for lieutenant governor of Georgia, and in 2014 he managed Greg Hecht’s campaign for Georgia attorney general.

Heyl worked for North Carolina candidates, too.

He was campaign manager for Charlie Sanders’ 1996 democratic primary campaign for the U.S. Senate. Sanders lost to Harvey Gantt. Heyl was a consultant for John Arrowood’s 2008 campaign for the N.C. Court of Appeals and June Atkinson’s 2012 campaign for superintendent of public instruction.

Will Heyl leave DEQ to help Cooper as he begins his re-election campaign?

“No,” Thorpe said.