Political progressives aren’t the only ones who see value in adding more “progressivity” to the state’s personal income tax. A Republican-sponsored bill that won unanimous support last week in the N.C. Senate would accomplish that goal.

But the proposal spelled out in Senate Bill 818 (and addressed on a different timetable in the House budget plan) boosts progressivity — earn more money, and you pay a higher tax rate — without sacrificing the growth-enhancing benefits of the state’s flat income tax rate.

Yes, North Carolina has a flat tax.

Sometimes that fact gets lost in debates over state tax policy. The major state tax reform package approved in 2013 and signed into law by Gov. Pat McCrory scrapped a three-tier, progressive income tax system and instituted one new, flat rate.

Moreover, that rate, initially set at 5.8 percent, was lower than the lowest rate under the old system. In other words, the income tax rate went down for every taxpayer in the state.

(Yes, it was possible for a taxpayer to end up with a higher overall tax burden under limited circumstances. Still, the best projections estimated that the average taxpayer in every income group in North Carolina would benefit from a lower overall tax burden because of 2013 reforms.)

And the income tax rate continues to drop. Taxpayers face a flat 5.75 percent rate this year. It drops to 5.499 percent in 2017.

Lowering tax rates generates benefits for the state’s economic growth. You don’t have to believe me. But your counterargument better take into account the vast majority of peer-reviewed academic journal articles from the past quarter century. Those academic studies support the notion that lower tax rates help spur stronger economic growth rates.

But this isn’t the end of the story.

Critics point out, correctly, that the biggest beneficiaries of a new flat tax rate are those who had been forced to pay higher rates in the past. While everyone benefits, those who paid the highest rates under a progressive system benefit most from the conversion to a flat tax.

Still, a flat tax does leave room to offer additional tax relief to low- and middle-income households. It is false to claim that the state’s income tax structure can feature either flat rates or progressivity.

One tool for addressing both goals is the standard deduction. This is the amount of income removed from a household’s tax base before any other tax calculations move forward.

When lawmakers first instituted the state’s new flat tax in 2013, they more than doubled the standard deduction. Prior to the reforms, joint filers saw a standard deduction of $6,000. That number was $4,400 for a head of household and $3,000 for a single filer. Today, those numbers stand at $15,500, $12,400, and $7,750, respectively.

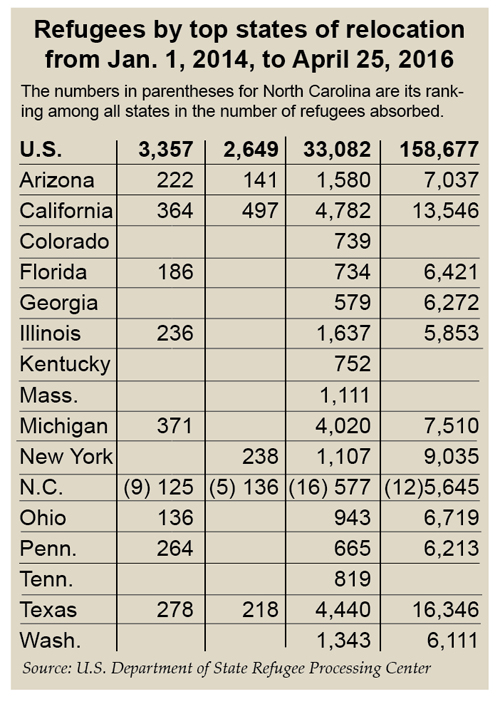

The presence of a standard deduction means that even the new flat tax system has two tax brackets: a zero bracket that covers all income up to the limit of the deduction and the 5.75 percent bracket that covers all additional income.

The higher the standard deduction, the higher the zero tax bracket. In addition, a higher standard deduction also generates more progressivity in “effective” tax rates — the rates people actually pay once all calculations are completed.

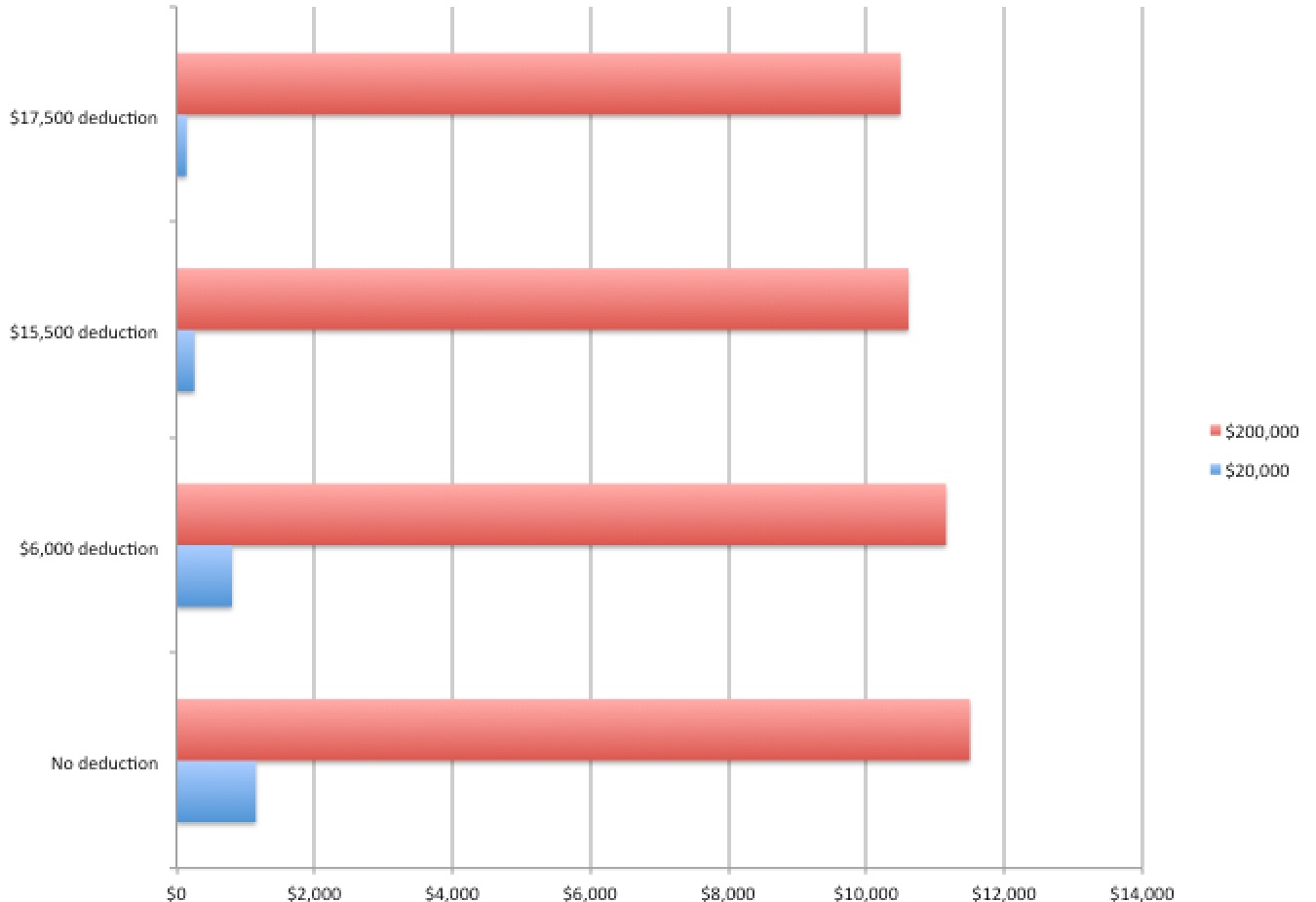

Think about it this way: If the flat tax rate kicked in with the first dollar the taxpayer earned, then the effective tax rate would be equal to the flat tax rate (setting aside any other tax credits or exemptions). If you earn $20,000 or $200,000, you would pay an effective tax rate of 5.75 percent this year. That translates into a tax bill of $1,150 for the lower-income earner versus $11,500 for the high-income earner. The second taxpayer earns 10 times as much money and pays 10 times as much in income taxes.

The standard deduction changes that scenario. It provides the same dollar amount of relief for each taxpayer — based on filing status — but the impact is proportionally greater for those at the lower end of the income scale.

Let’s consider the two taxpayers above. We’ll say that both cases represent households with joint tax filers. Under the pre-2013 system, both taxpayers could take a $6,000 standard deduction. Applying the current 5.75 percent tax rate to the remaining income, the respective tax bills drop by $345 for both households to $805 for the lower-income taxpayer and $11,155 for the high-income earner. The “effective” tax rates for the two taxpayers now drop from 5.75 percent for both taxpayers to roughly 4 percent for the $20,000 household and 5.58 percent for the $200,000 earner.

Now let’s apply today’s joint-filer standard deduction of $15,500. Applying the current 5.75 percent tax rate to the remaining income, the respective tax bills drop by another $546.25 for both households to $258.75 for the lower-income earner and $10,608.75 for the higher-income earner. The effective tax rates drop to 1.3 percent for the $20,000 household and 5.3 percent for the $200,000 household.

Two effects should leap out immediately as you read the scenarios above. First, while both households see tax benefits from an increase in the standard deduction, the impact for the lower-income household is greater proportionally. An $1,150 tax bill falls to $258.75. That’s a decrease of more than 77 percent. In contrast, the higher-income household’s bill drops from $11,155 to $10,608.75. That’s a decrease of less than 5 percent. (Even if you limit consideration to the changes enacted since 2013, the low-income earner’s income tax bill drops by two-thirds, while the higher-income earner’s income tax bill still drops by less than 5 percent.)

The first chart illustrates this impact.

The second clear impact of a higher standard deduction is that the lower-income household enjoys a much larger cut in its effective tax rate — from 5.75 percent to 1.3 percent. The higher-income household also enjoys a less substantial cut from 5.75 percent to 5.3 percent.

S.B. 818 would make these differences even more pronounced. It calls for raising the standard deduction by $2,000 over two years. Applying the proposed $17,500 standard deduction to our scenario, the respective tax bills would drop by another $115 to $143.75 and $10,493.75, respectively. The effective tax rates would drop to 0.7 percent for the $20,000 household and 5.2 percent for the $200,000 household.

The second chart shows the impact of the standard deduction on effective tax rates.

It would be hard to argue that there’s no significant difference between a 5.2 percent effective tax rate and a 0.7 percent rate. If you’re looking for progressivity in your income tax code, there it is. Want more progressivity? You can raise the standard deduction even higher.

Yet that progressivity does not require a higher marginal tax rate. Because the next dollar a high-income taxpayer earns is taxed at the same flat rate as the previous dollar (5.75 percent), there is no economic disincentive for people to continue working and earning additional money. There is no additional drag on economic growth.

It remains to be seen whether the N.C. House will go along with the Senate’s plan. The House might push instead for a similar proposal in its budget plan that phases in the increased standard deduction over a slightly longer time period.

If the two chambers can reach an agreement, they will be keeping the benefits of a flat tax while building in the progressivity that allows low- and middle-income families to keep a larger percentage of their money out of the tax man’s hands.

Mitch Kokai is an associate editor of Carolina Journal.