In some circles, it is thought that for a community to be said to truly exist, it must be “World Class.” It is assumed that each community aspires to be a World Class Community, no matter the cost. What brings a WCC to life, like the magician’s hat to Frosty the Snowman, is light-rail transit.

For a metropolitan area not to be a WCC is for it to be an afterthought, a regional castoff, a villa of bumpkins on the verge of downtown tractor pulls (if not downtown hair pulls) that will never ever host an Olympics or even a national political convention. It’s like hell for communities, the kind of hell where people are generally content and happy, other than the enlightened choochoorati and neglected handful of would-be riders.

It has long been a dream of Wake County planners, rail romantics, smart-growth fans, and media interests that Wake County would adopt light-rail transit. So when a panel of outside experts came in and reiterated the obvious but disenchanting fact that no, the area is not nearly dense enough to make rail transit at all feasible, they were crestfallen.

The disappointment was as evident as the quivering pout on the face of a 3-year-old told that, “No, honey, you can’t grow a hotdog tree by planting Red Hots. Please stop wasting them.”

Earlier this month, three outside transportation experts participated in a panel for Wake County commissioners on the subject of the county’s long-range transit plan. Neighboring Durham and Orange counties have recently put additional pressure on Wake to join them in rail transit by passing half-cent transit sales taxes, but Wake’s leaders have resisted joining them. Rail transit advocates see Wake as the missing link, the holdout, the stick-in-the-mud, the wet blanket.

Based on what commissioners heard from the experts, they’ve been the responsible adults all along.

A very disappointed News & Observer reported that panelists said:

Wake won’t be ready for trains until it has heavier urban density, worse traffic jams and more people riding buses who could be expected to ride trains later. … Wake County was not likely to attract the federal funding it would need for a light rail line, and it doesn’t have a dense downtown employment center that would support rush-hour commuter trains.

The verdicts were so uniform, it seems, that the three experts were moved to explain “they had not shared notes in advance.”

The panelists were:

Commissioner Paul Coble, whose rail reluctance earned him the N&O’s worst printable invective (I don’t know what an “archconservative” is, Mabel, but hold me; I’m scared), heard vindication from the panelists:

”What I’m hearing them say is: What you did was wise,” Commissioner Paul Coble of Raleigh said later. “Don’t rush into it just because it’s the thing to do. Understand what you’re going to do and what it’s going to cost you.”

To be sure, it wasn’t the first time commissioners had heard that. Last March, a planning expert praised the Wake County commissioners for having “done the right thing” by not putting a transit tax on the ballot.

That expert was John Pucher, a professor in the Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy at Rutgers University in New Jersey, who has over 40 years’ experience in transportation planning. At the time Pucher was a visiting professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in the Department of City and Regional Planning.

Pucher, who “supports alternative modes of transportation,” also took the region’s density into consideration. “It’s just so difficult in this very decentralized, very sprawled metropolitan area,” he said.

In 2012, two transportation experts also cautioned Wake County about its rail transit plans. One was David Hartgen, a widely known and well-respected transportation scholar, an emeritus professor of transportation studies at UNC-Charlotte and president of The Hartgen Group. Hartgen had previously directed the statistics and analysis functions of the New York State Department of Transportation and served as a policy analyst at the Federal Highway Administration.

The other expert was Thomas Rubin, a consultant based in Oakland, Calif., with over 35 years of experience in assessing and directing the capital and operating budgets of numerous transportation agencies. Rubin had served as the chief financial officer of the Southern California Rapid Transit District (now Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority) and the Alameda–Contra Costa Transit District in Oakland.

Among their many other findings concerning Wake County, including very high costs per rail rider trip, per rider, and per passenger mile, Hartgen and Rubin included this:

The proposed Commuter Rail and Light Rail services are inappropriate for a region of this size and density. The region’s density is lower than all but three of the 34 regions now operating rail transit service.

Density isn’t a problem for the N&O. With costs, experts, and geographic factors all conspiring against the region’s ascent into light rail heaven, they tried out several alternate arguments. These included an appeal to peer pressure — everybody [Durham and Orange] is doing it! — and attacking Coble and other commissioners for being political ideologues and cowards who probably want to turn roads into parking lots (you know, since doing nothing about light rail means doing nothing about transportation, period).

A novel argument tried to expose the problem of expert consensus of the “we promise we didn’t share notes” level of uniformity:

Critics merely rolled out the same tired reason for doing little: The region isn’t crowded enough to supply passengers for light rail and commuter trains. (Emphasis added.)

Another argument, however, granted that “tired” reason in order to apply even more peer pressure:

It may be true that this region currently lacks the density needed to support different kinds of mass transit, but that’s been an argument in other cities that went ahead anyway.

What’s the regional version of the responsible adult’s retort to this appeal? If Durham and Orange County voted themselves off a cliff, would you do it, too?

In a later editorial, the N&O decided to attack some of the messengers. Polzin’s center, his credentials notwithstanding, generally opposes rail travel. (Marsella, who wasn’t mentioned, has generally favored rail travel.) And Staley “is connected to the Reason Foundation, a think tank whose board members include oil industry titan David Koch, an ultraconservative political activist and contributor.”

Well, the editorial sneered, so much for the panel’s credibility. As if the ad hominem altered the same tired old facts.

The paper expected but didn’t quite trust its readership to recoil with horror at the mere mention of a Koch brother’s name. Koch is a well-known libertarian philanthropist, so it took yeoman’s work on the N&O’s part to recast him as just two things: “oil industry titan” (de facto evil) and “ultraconservative.”

Other recent uses of that appellation in the N&O have been to describe the Sunni Salafi movement in Yemen, the powerful Revolutionary Guard Corps in Iran, and the Islamic Nour Party that backed the overthrow of President Mohammed Morsi in Egypt. The implication behind its selection is clear. The reason for it is pathetic.

Even the “same tired argument” involves an actual argument. Trying to discredit the argument by playing Six Degrees of Separation with some bogeyman of your own device, whose beliefs you don’t dare characterize properly, is feckless.

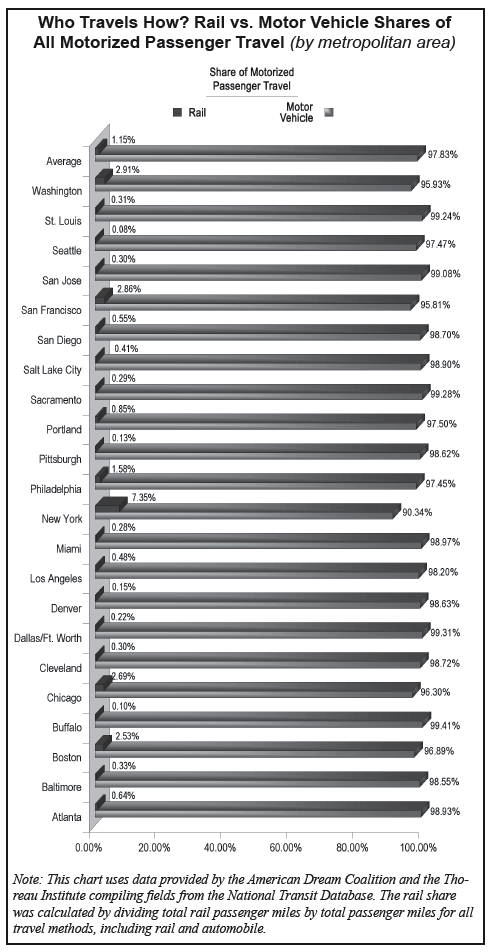

To address the one near-argument in favor of light rail (hey, other peers lacking density did it anyway), let the John Locke Foundation’s City and County Issue Guide suffice. An entry on Public Transit discussed these other cities and warned against the “romance of rail.” It included the graph below comparing the rail and motor vehicle shares of all passenger travel in several major metropolitan areas.

Please note that in the graph, each city has two bars, one for rail and one for motor vehicles. It’s just that the rail share bars are so infinitesimal that you might miss them. The average for rail is, after all, only 1.15 percent.

Jon Sanders (@jonpsanders) is Director of Regulatory Studies at the John Locke Foundation.