It was a mid-November day in 1980. I was sitting in the co-pilot seat of the Cessna 180 Marine Fisheries floatplane riveted on the scene in front of me. We were traveling south, flying under the radar of the Cherry Point Marine Corps Air Station, mere feet above a vast expanse of black needle rush marsh.

Wayne Maxwell was a careful and confident pilot. At that time, Wayne was in his mid-40s, and behind the control yoke in his Marine Fisheries Officer uniform, he appeared relaxed and in total control. His mostly gray hair was a testament to his flying skills and good fortune. Earlier, we had finished a day of CAMA (Coastal Area Management Act) compliance surveillance in the northern coastal counties and topped off the wing tanks at the fuel depot in the Swanquarter Ferry Basin. Leaving Swanquarter, we headed south to the Marine Fisheries home base in Morehead City on Bogue Sound.

At this particular moment, I was a causal sightseer doing speed beachcombing as the marsh streaked under the cowling in the late afternoon light. We were so close to the deck and going so fast that I would glimpse an object in the marsh, and my brain couldn’t process what it was in real-time. There were sections of the dock, the broken bow of a skiff, numerous busted coolers, milk jugs, white Clorox bottles, twisted orange life preservers, clusters of line, and crab pot floats. Long lost treasure washed out from Davey Jones Locker.

Wayne raised his voice over the drone of the prop and the whine of the air-cooled continental six-cylinder engine, interrupting my beach-combing concentration. He was reminding me to watch out for military jets. Encountering a jet at this low altitude was not unusual. They liked to fly below the radar too.

The military-restricted air space is roughly a million acres overlaying the NC coastal area. Military air traffic controllers are not always friendly or accommodating. Because of this, Marine Fisheries pilots working Pamlico Sound did most of their occupation below the treetop level. They were excellent pilots and were used to that type of work. They could bank over a skiff, look down into the five-gallon buckets, and tell if you were clamming, oystering, scolloping, picking up conchs, or just packing a can of Pepsi and a sandwich for lunch, all while flying by at 100 knots! Not an easy feat!

But the military jet encounters could be heart-stopping. It doesn’t help that military jet pilots are typically cocky, arrogant, and invincible, at least in their own minds. But It would probably get into anybody’s head to be 20-something, seated behind the stick of the latest $30M plus, state of the art, Mach 1.5, full afterburner, Star Wars-like spaceship, and going head to head with your best buddy in a mock dogfight. No video game will ever compare with that!

And I am sure there were days the military air traffic control officer watched three or four jets take off from the base at Cherry Point, only to be sitting there a few minutes later staring at a blank radar screen. He knew there were planes out there but didn’t have the foggiest idea where they were! Flying below the radar is apparently a coastal aviation pass time both military and civilian pilots joke about around the water cooler!

Wayne and I made it home that day undetected and without incident, but there were other days where the military jet scare was tattooed on my brain. There was the time we were conducting CAMA surveillance along the southern edge of Albemarle Sound when we happened to see a faint puff of smoke off in the distance. The jets were just two slender horizontal lines barreling straight down the river towards us.

We flared right, a split second before two F-14 Tomcats (think Top Gun), with their wings extended, streaked by with only slightly more altitude through our previous position. They were out of the naval air station in Virginia Beach doing a practice bombing run on the Mackeys Ferry Sawmill that happens to line up directly with the centerline of the Chowan River. No one should ever be allowed to fly a plane that big, that fast that low.

The second incident occurred over a remote tributary of the Bay River in Pamlico County. It was early afternoon, and the lunch special from a local greasy spoon, the climbing and diving, the drone of the engine, and the smell of aviation fuel, had left me woozy. In the midst of fighting nausea, I tried to keep my eyes on the ground to complete our task.

We were gently rising and banking slightly to the right when I happened to notice another plane shadow along with ours on the ground. The next instant, an A-6 Intruder roared by directly overhead. It had overtaken us from behind, and when I snapped around to look, the windshield was full of the jet underbelly. You could have reached out and touched it. I wonder if the air traffic control officer at Cherry Point was giggling in a fit of revenge as he saw our separate transponder signals nearly converge on the radar screen.

Eastern North Carolina has a rich aviation heritage. Along with the burden of military air space control and the occasional, errant sonic boom, there is the benefit of well-paying, secure employment for thousands of families. In the spirit of building on this rich aviation heritage, I would like to propose several projects that Central Coastal NC is in desperate need of now.

Some of these ideas take a new look at old proposals, proposals that have been put on the back burner because of the cost constraints and permitting difficulty. A couple of these proposals are new, however. What is unique about this package, though, is joining these proposals together into a deliberate initiative pursuing one specific industry: aerospace.

The aerospace industry is booming and Eastern North Carolina is uniquely qualified to assume a prominent role in this boom. The Global Transpark in Kinston has been the pioneer in this field and North Carolina officials would be wise to continue building on that success. The NC Department of Transportation currently operates the Global Transpark. However, there is some discussion as to whether it may be better served as part of the NC State Port Authority. At any rate, there seems to be a high degree of cooperation between the key agencies. Other players important to initiating any sort of effort like this are the elected officials of Carteret and Craven counties.

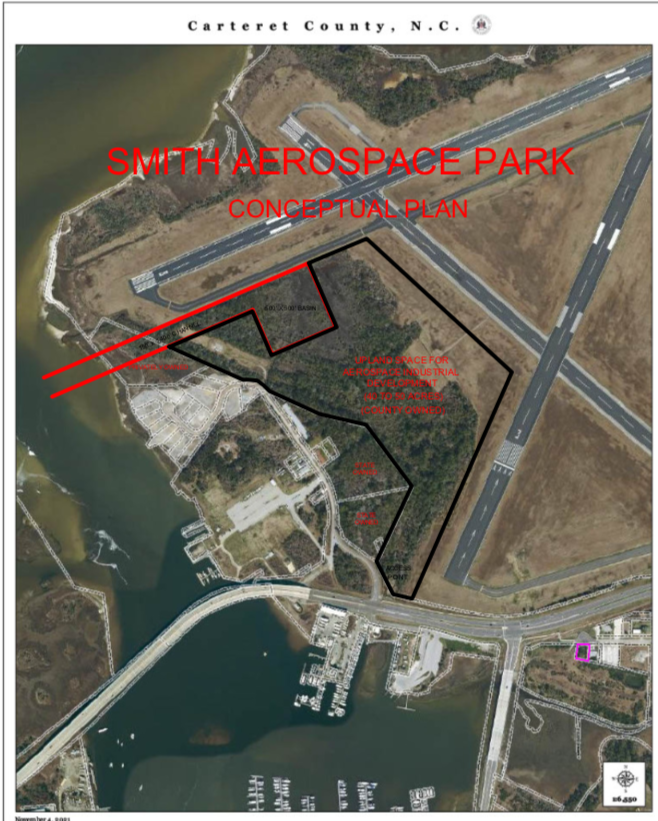

The central idea is shown in the attached illustration. This is a conceptual plan for an aerospace park at the Michael J. Smith Field airport in Beaufort. This facility is shown adjacent to the new Beaufort Bypass on what is currently unused county-owned and state-owned land.

The rationale for this is that clients of the Global Transpark are currently shipping relatively small aircraft parts through the Morehead City State Port to be assembled elsewhere. There are obvious limits as to how big these parts can be due to the physical highway and street constraints. This conceptual facility will assemble these relatively small parts from the Transpark into a more complete aircraft fuselage and wings. The proposed channel and basin carry the large, assembled parts out of the park, under the bridge, to the main Port facility for loading and shipping. Alternatively, large parts can be brought in and finished into complete aircraft.

The Beaufort Airport also has an advantage over other inland airport locations for basing supersonic aircraft facilities. It is illegal to break the sound barrier over the continental U.S. Having the ability to easily access flight paths over the ocean, where it is not illegal, would be a great advantage for such aircraft manufacturing clients.

Concurrent with this project and necessary to the plan would be the long-awaited extension of Runway 26. And since we are thinking outside the box here, Hwy 101 could be maintained in the present location by building a tunnel, or “Wunnel.”

The development of such an aerospace facility would profoundly increase the numbers used to justify the long-discussed and hoped-for Northern Carteret Bypass. Incorporating train tracks in the road design and using the opportunity to extend the natural gas lines would provide even more justification for building the highway.

Nelson Paul is a real estate agent, former NC Coastal regulator, inventor, husband, and father of four, and a grandfather of seven.