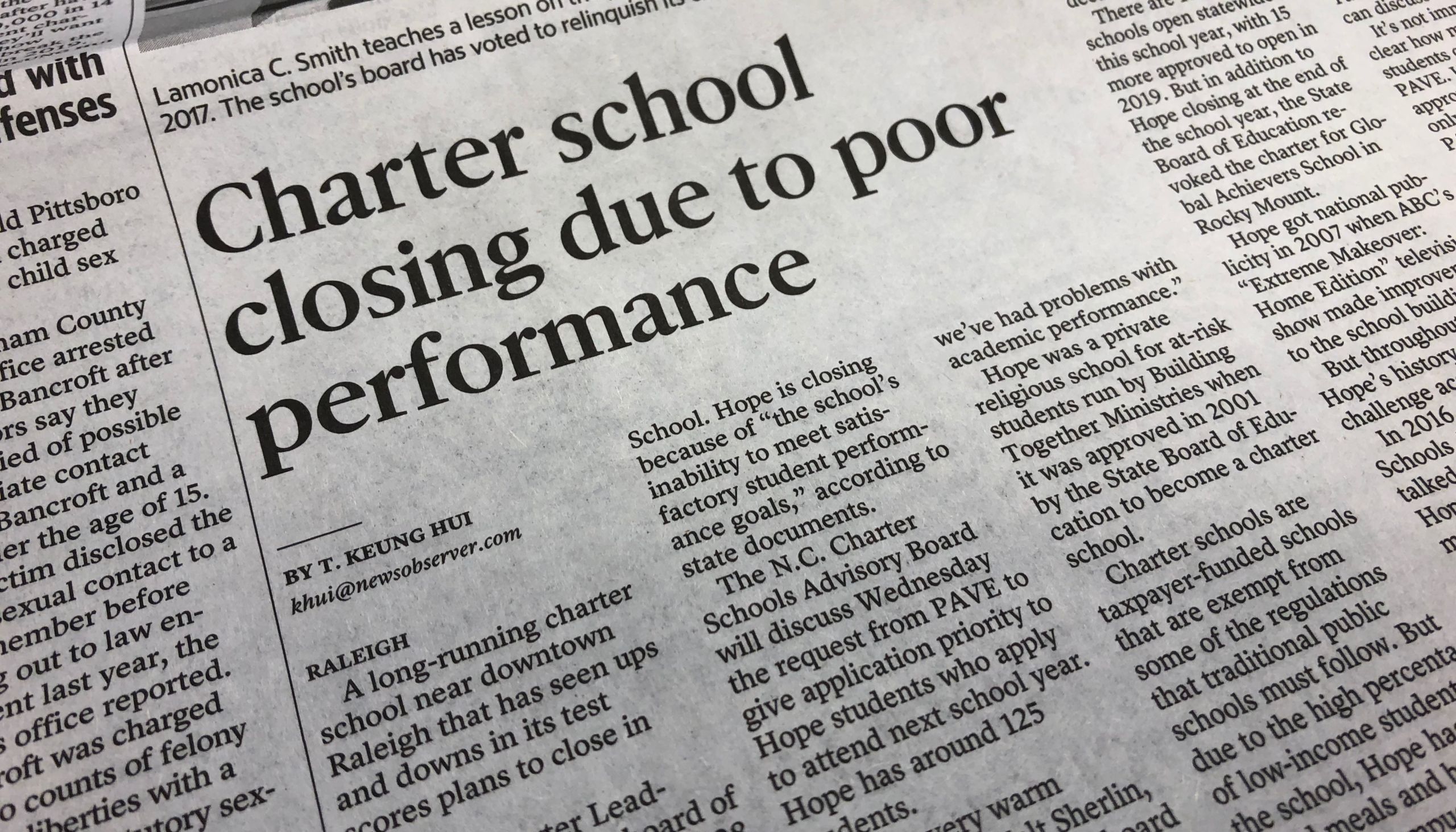

It’s hard to feel good about the following headline: “Charter school closing due to poor performance.”

But this observer has to admit to at least one positive reaction while reading the sad news spelled out in the Dec. 11 edition of the Raleigh News and Observer. While contemplating the story of Hope Charter Leadership Academy’s struggles, I couldn’t help but think: This is what’s supposed to happen to a charter school that underperforms.

The demise of Hope Charter, located near downtown Raleigh, offers a sharp contrast to traditional district schools that fail year after year. In almost every case, those schools continue to operate with no threat of closing. While Hope Charter students and families must seek other educational options, many of their counterparts in failing schools across the state remain stuck with the status quo.

Short of a shutdown, even efforts to shake up operations of a failing district school tend to face an uphill battle. Witness the protracted fights over placing two elementary schools — one in Robeson County and the other in Wayne — in the state’s relatively new Innovative School District. That district targets the state’s worst-performing district schools. It allows them to continue operating under new management.

Imagine the outcry if state or local education officials had recommended an alternative: shuttering those schools completely. It’s safe to say that option would not have proceeded as smoothly as the process that will lead Hope Charter to close its doors.

Charter school advocates often point to good news associated with these publicly funded schools that operate outside the control of traditional school systems. And they have strong evidence on their side.

The John Locke Foundation’s K-12 education expert, Terry Stoops, noted this fall that a higher percentage of charter schools (42 percent) earned A and B grades from the N.C. Department of Public Instruction in 2017-18 than their district school counterparts (35 percent). Charter schools made up 7.8 percent of those higher-grade schools, even though charters represent just 6.6 percent of the more than 2,500 graded public schools statewide.

On the other end of the scale, eight charter schools (5 percent) earned F grades, while 83 (4 percent) of their traditional district school counterparts failed to make the grade. Charters represented 8.8 percent of all failing schools, according to the state’s grading system.

One major difference, of course, is that each failing charter school faces the threat of following Hope Charter’s path to closing. Few, if any, of the dozens of failing district schools are likely to hear any suggestion that they shut down.

The prospect of closing forces struggling charter schools to innovate or disappear.

Innovation remains a realistic option. Ask Richard Vinroot, the former Charlotte mayor and Republican candidate for governor. Vinroot shared with state lawmakers this spring the story of Sugar Creek, the charter school he helped start in Mecklenburg County.

Sugar Creek’s early performance results fell well short of Vinroot’s expectations. He conveyed his concerns to school director Cheryl Turner. “Our numbers were exactly like the poor schools at [Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools] — no different,” Vinroot said. “We had no gym. No playground. I said, ‘Cheryl, we need to shut this darn thing down. Why are we taking kids in our school who aren’t doing any better than anywhere else? We need to shut it down.’”

As Vinroot recounted during his April legislative presentation, Turner asked for another year to find a way to boost the school’s performance. Two decades later, a school that started with about a quarter of its students meeting grade-level proficiency boosted that total to 60 percent.

In 2016-17, Sugar Creek’s African-American students scored 12 points higher on standardized tests than their CMS peers and 19 points higher than African-American students statewide. Sugar Creek’s Hispanic students scored 19 points higher than those in the surrounding school district and 21 points higher than the statewide average. Among all economically disadvantaged students, Sugar Creek topped CMS by 18 points and the statewide average by 21.

The school eventually expanded into high school grades. All 30 members of its first graduating class were expected to go on to college. As the school compiled these achievements, 94 percent of Sugar Creek students qualified for free or reduced-price lunches, Vinroot said.

It would be great to see repeat performances of Sugar Creek’s success story. State leaders would be wise to give new charter schools sufficient time to mirror Turner’s impressive turnaround.

But some charter schools won’t make it. Those that can’t find the key to success should shut down. Just as the top-performing charters offer examples for other schools to emulate, the shuttered charters should provide evidence of education approaches to avoid in the future.

Yes, it’s sad to read about a “Charter school closing due to poor performance.” But that’s a better headline to see than “Charter school lingers on despite repeated poor performance.”

Mitch Kokai is senior political analyst for the John Locke Foundation.