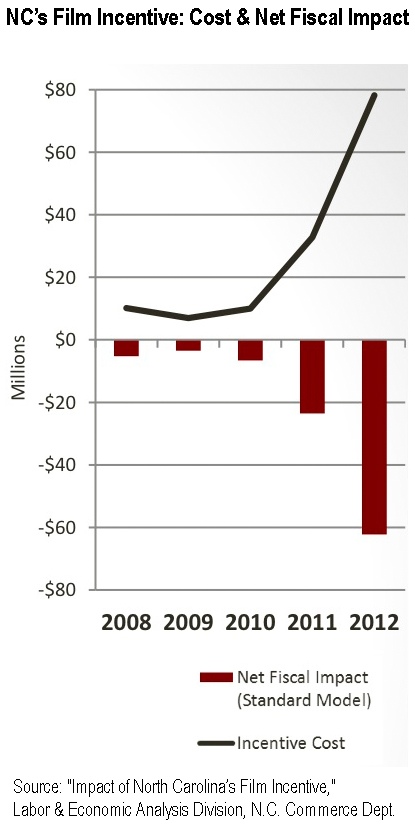

A presentation prepared by the N.C. Commerce Department’s Labor and Economic Analysis Division finds a net “negative budgetary impact” of North Carolina’s film incentives.

In 2012, according to the presentation, $76.9 million in film credits were claimed, with a net fiscal cost of $62 million. That would amount to about 19.4 cents returned to state revenues for every dollar spent.

The methodology used in the analysis is unclear. One concern is that benefits and costs in the analysis don’t align. Benefits include “indirect and induced jobs created through multiplier effects” and “new tax revenue from new economic activity,” but costs do not account for “indirect and induced jobs lost” because the state redirected money from other uses with their own multiplier effects. Nor does the analysis account for “lost tax revenue from lost economic activity.”

To explain further: If through taxation government takes money that already has productive purposes in other areas, and instead puts the money in a government-selected area, it’s not enough to quantify downstream effects in the government-selected area when government action has put an end to all downstream effects elsewhere. Especially when the stated reason is to grow the economy, which is what programs such as film incentives seek to do.

If you forcibly transfer wealth from other parts of the economy in order to grow one industry, and you’re doing that to make the state’s economy better, then you don’t know anything about whether the forced transfer works if you focus only on that one industry’s growth. How does that industry’s growth compare with the forced declines elsewhere in the economy?

You’re also further deluding yourself if you subsequently assume that the existence of the entire industry now rests on the transfer.

As I explained last year:

Having the state intervene to take some of those resources and force them into the less profitable venture would, it is true, produce direct and subsequent economic activity where it wasn’t. But it also takes away from greater direct and subsequent economic activity where it was.

The loss of economic activity from areas where investors and consumers would have directed resources is not studied or reported on as frequently.

If a study intends to prove that an incentive is attractive to the favored industry, it will focus just on the direct and subsequent benefits of the industry. The study will rely on an input/output model such as IMPLAN that doesn’t account for opportunity costs and doesn’t require an economist to conduct.

If a study intends to test whether an incentive is good for the overall economy of the state, it will weigh the direct and subsequent industry benefits against the direct and subsequent lost economic activities overall. It will use a cost/benefit framework and will most likely be conducted by an economist.

This distinction is important to keep in mind as state officials await a study of film incentives, to be done, apparently, from a perspective of supply chain management.

No one should be surprised that the results of that now-released study fail to account adequately with the costs associated with film incentives.

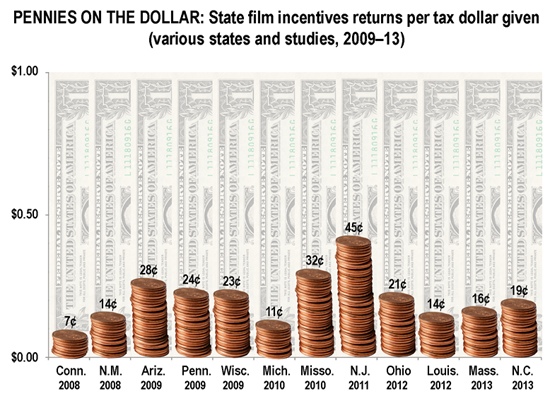

Other state programs are also returning just pennies on the dollar

Nevertheless, a finding of 19 cents returned to the state for every dollar spent on film incentives would be in line with the findings of many other studies conducted for various state agencies or legislatures of their film incentives programs:

Or has a foundational economic assumption been overturned?

Note that these findings stand in stark contrast with industry studies of various state film incentives, which among other things tend to ignore opportunity costs entirely while assuming the incentives are responsible for all film production in the state, rather than marginal productions. They also tend to produce extremely inflated estimated returns on investment.

Some examples include the Motion Picture Association of America’s 2014 study for Florida, which projected a return of anywhere from $5.60 to $20.50 in state revenue per dollar of revenue spent on film incentives, Ernst & Young’s 2009 studies for New Mexico ($1.50 per dollar, nearly 11 times greater than the estimate by the New Mexico Legislative Finance Committee’s study) and New York ($1.90 per dollar), and of course the MPAA’s 2012 study for North Carolina, ($8.99 per dollar for “Iron Man 3”).

Findings with such enormously high multipliers are simply not believable. It is as if “the authors believe they have overturned the fundamental basis for microeconomic theory,” to quote from the Beacon Hill Institute economists’ peer review of a study purporting economic benefits of renewable energy in North Carolina (and projecting a multiplier of 19.3). The quote in context, because it has bearing on film incentives studies as well:

[T]he baseline assumption any reasonable economic analysis should make is that private firms maximize profit.If it were the case that cost-savings of this magnitude were available, then private energy firms would have been leaving hundreds of millions of dollars on the table — that is, definitely not maximizing profit — for no apparent reason. If the authors believe they have overturned the fundamental basis for microeconomic theory, they should specify why.

Of course, if one started with the expectation that even with film incentives, state governments haven’t overturned the fundamental basis for microeconomic theory, one would find more credible these recurring findings of pennies on the dollar in returns on those involuntary investments.

Jon Sanders (@jonpsanders) is Director of Regulatory Studies for the John Locke Foundation.