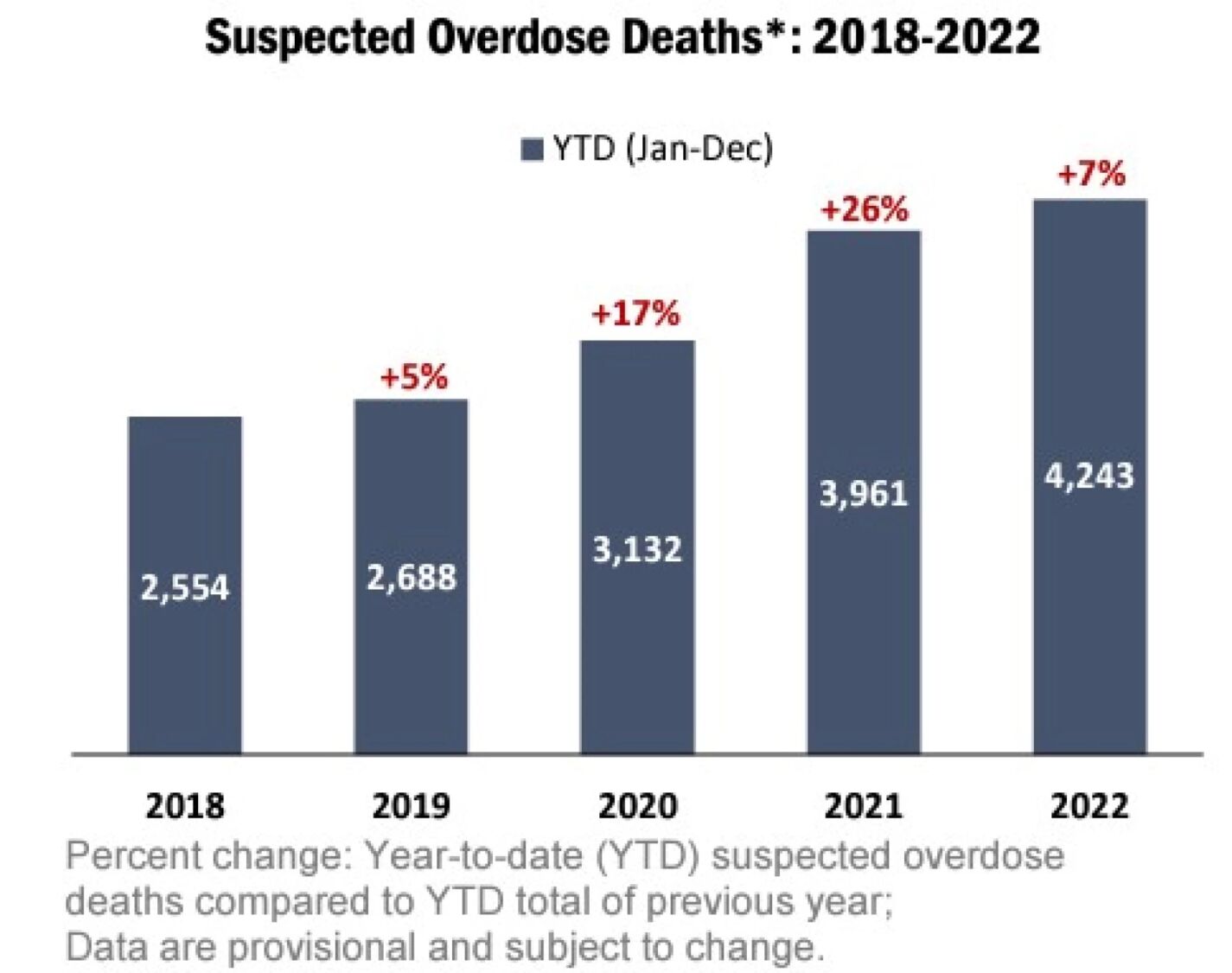

According to the N.C. Medical Examiner’s Office, 4,243 North Carolinians died of suspected drug overdoses in 2022. This was a 7% increase over the year before, which was a 26% increase over the previous year, which was a 17% increase over the year before that, and on and on, as can be seen in the chart below from WFAE.

The data also showed 9,243 emergency-department visits for opioid overdoses in 2022. In 2013, that number was only 3,263. Nationally, we’ve gone from about 5,000 overdose deaths a year until the late 1990s, then a sharp rise to more than 100,000 a year today. This makes drug overdose the largest cause of death for adults 45 and under.

The impact of these spiking drug death and dependency rates are rippling across the state. I’ve spoken a number of times to the leaders of a statewide group of mothers, the Lost Voices of Fentanyl, who spend every day fighting to keep the memory of their children alive and working so other families don’t have to face the same fate. The pain and loss is immediately evident when speaking to them.

There’s also the impact to North Carolina’s downtowns, many of which are becoming dangerous and run down due to the homelessness and crime being fueled by severe mental illness (SMI) and drug addiction.

WRAL recently documented how the once vibrant downtown of Chapel Hill, centered around Franklin Street, has become known as a no-go-zone for many college students who used to frequent the bars and shops. The business owners, understandably, are not happy about it.

The same is being seen in Asheville, as reported by the Asheville Watchdog in a multi-part series. They document a rise in crime, homelessness, intimidation, open drug use, and overdoses. The once-popular tourist town in the mountains is now getting a reputation as unattractive and unfriendly and has been given the unfortunate moniker “Trasheville.”

So it’s not just the individual users being affected. It’s also their families and their communities.

Facing the problem head on

Many are focusing on cracking down on the supply, with added fees, harsher sentences, and more funding to investigate distribution networks. Recently filed N.C. Senate Bill 189 takes this angle, which is certainly a necessary part of the equation. The bill focuses specifically on fentanyl, since it is such a large part of the current overdose problem.

But when there is high demand for a product on the black market, it can often be an elusive problem to solve by simply attacking the supply.

In December of 2022, the John Locke Foundation released a report addressing the drug epidemic, as well as the closely connected mental health crisis. The plan, as it relates to substance abuse, can be summarized in three parts, which focus on treating drug addiction like a debilitating condition that needs treatment, not as a free choice that just needs its harms reduced.

The first part is to get rid of certificate-of-need (CON) laws in North Carolina’s health care system. These outdated laws require health providers to purchase expensive permission slips from the government in order to practice medicine in areas that the provider is already certified. This limits supply and drives up costs, including in drug treatment.

While many of the CON laws survived a recent Medicaid expansion deal at the legislature, thankfully, according to Sen. Ralph Hise, the CON laws that limited behavioral health and chemical dependency beds will be completely eliminated. That is a big deal and will go a long way in creating more supply of treatment options in the state.

So, with element one already accomplished, let’s look at parts two and three — involuntary inpatient treatment for those who are a danger to themselves and others, and involuntary outpatient treatment for those who are not yet a danger.

Involuntary commitment

While it may sound extreme to some, involuntary commitment is a fairly simple solution to the problem. If the same 10 people gather in the center of the city every day, taking drugs and harassing those engaged in legitimate activities, they should be removed and forced to get treatment. Cities on the West Coast (like Seattle, San Francisco, Portland, and Los Angeles) who have taken a more enabling “harm reduction” approach, giving out needles and limiting legal consequences, are seeing these open drug camps multiply.

Involuntary commitment of those whose behavior puts the user and the public in danger is actually the more humane response. It’s not uncommon in those West Coast cities for children to have to dodge used needles and human feces on their walk home from school.

Some states, like Ohio and Kentucky, have passed Casey’s Law, which allows families and friends to file for an involuntary commitment order. Many of those in the video below say they were angry and felt their rights were being violated when they were first taken off the streets. But after some time in treatment, and then many years sober, they now see how dangerous they were to themselves and others and appreciate someone stepping in.

According to Clayton Cramer, who wrote the JLF report, “North Carolina’s involuntary commitment laws appear sufficient to address most situations without becoming an echo of the abusive practices in the past.”

Unlike the states under Casey’s Law, in our state you do not even need to have a personal relationship with the person. Anyone with “sufficient knowledge” of the person’s need for treatment can file an involuntary commitment petition with the court. The petition can be seen below.

If a business owner has the same three people shooting heroin in his doorway day after day, driving away customers, they are legally permitted to file a petition. Someone who walks to work and is harassed by the same intoxicated panhandler every day can file. A police officer or nurse who has repeatedly saved someone’s life with Naloxone can also file a petition.

Often there are only a small group of people causing the problems in certain neighborhoods and city centers, and having them removed and given treatment will make life better for all parties.

Before citizens file these petitions, it may be best to speak with the county courts and health department to see how officials locally deal with involuntary commitment orders. If they are resistant to applying the process as described in North Carolina General Statutes at all, some public pressure might need to be applied on the matter.

After the court decides to evaluate someone, they may decide not to have them committed, but the person may be ordered to take part in either inpatient or outpatient treatment. How this treatment is paid for and what it should entail are long discussions.

But conservatives who favor safety-net programs for other people incapable of helping themselves should not see spending public money on these poor souls as a compromise of principle. Nor should they think that the person’s freedom is being violated. A person addicted to fentanyl or methamphetamine (often forced to support their habit by prostituting themselves or stealing from loved ones) is by definition not free. Their liberty is already compromised. The question should be how to re-establish it.

With CON laws limiting drug treatment on the way out and our flexible involuntary commitment statutes already in place, North Carolina has the tools to address the drug crisis. Now local leaders just need to step up and decide enough is enough.

The full John Locke Foundation report on mental health and drug abuse solutions in North Carolina is below: