The statistics on religion show both affiliation with and attendance at America’s churches are plummeting. And North Carolina is feeling the effects, with church buildings shuttering across the state due to lack of members and donations. This is a dangerous sign for the future of our state.

Ryan Burge — a Baptist pastor, data scientist, and author of the book, “Nones,” about the religiously unaffiliated — said in a 2021 article for Christianity Today, “If there’s one overarching conclusion that comes from studying survey data of American religion over the last several decades, it is that fewer people identify with an established religious tradition every year. The ranks of religiously unaffiliated, also called the nones, have grown from just about 5 percent in the early 1970s to at least 30 percent in 2020.”

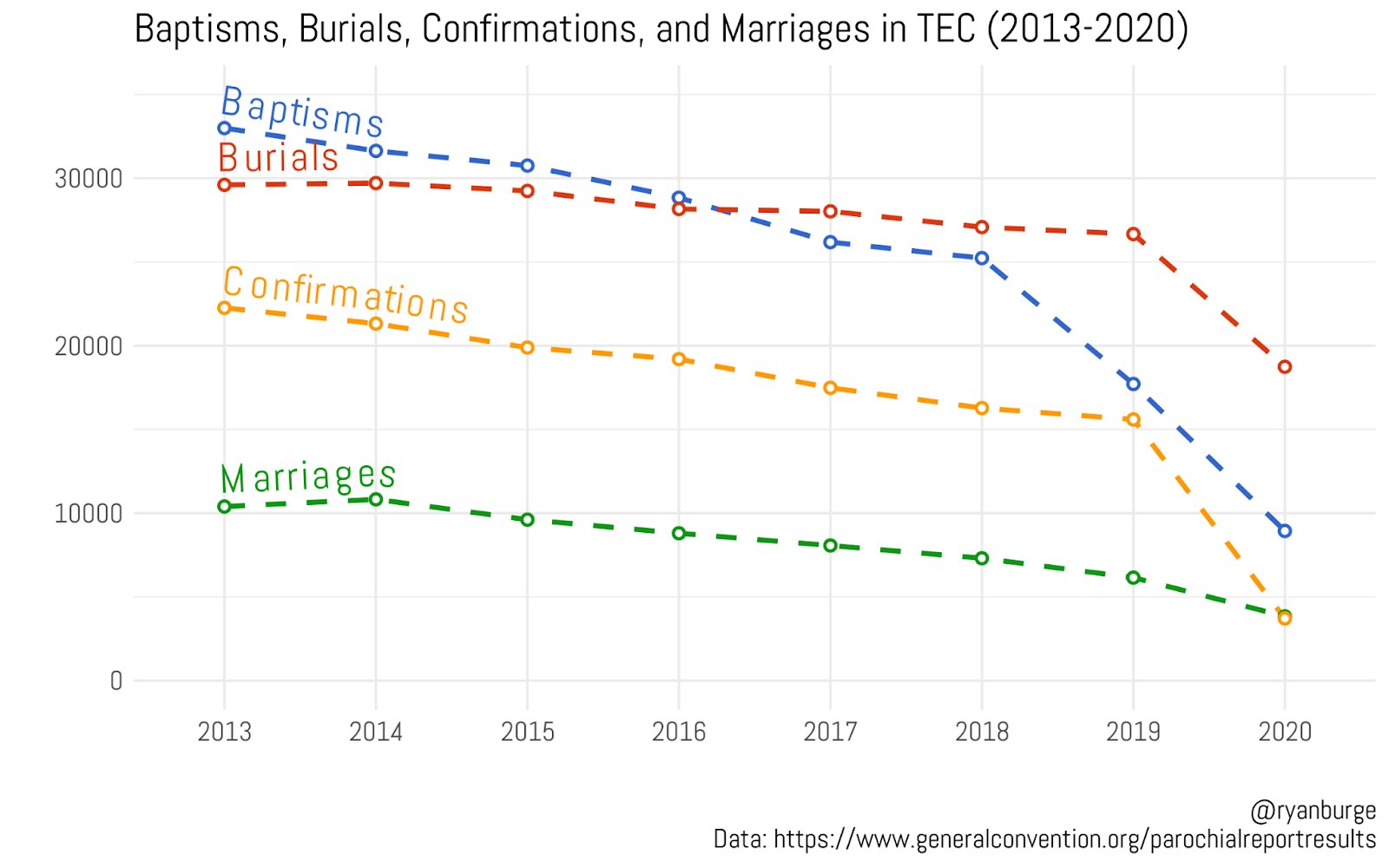

The “Mainline” denominations that historically defined America’s faith, like the Episcopal Church, Presbyterian Church USA, and Evangelical Lutheran Church, are each predicted to run out of Sunday attendees in 20-30 years. The Episcopal Church had burials exceed baptisms for the first time in 2017, and in 2020, that trend accelerated to the point where burials exceed baptisms, weddings, and confirmations, combined.

That was before COVID. Since then, the problem has accelerated even further, with N.C. Episcopalians losing a further 53% of their Sunday attendance in 2021 alone. But more conservative denominations shouldn’t feel smug about this, as the largest drops in church attendance are seen among more conservative people and states, partly because they had further to fall to catch up with their already secularized Mainline cousins.

North Carolina following suit

This brings us to North Carolina, where we are experiencing the affects of these national trends. This month, WSOC-TV published a story titled, “Churches across Carolinas forced to sell as they grapple with low attendance.”

The story highlighted that even before the pandemic started, more churches were closing than opening (4,500 Protestant churches closed in 2019 across the country), as the population moved from 92% Christian in 1972 to 64% in 2020. Younger generations are now majority non-Christian and getting more so.

“It’s kind of depressing,” a former attendee at one N.C. United Methodist Church told WSOC. “It was just always a good church, good people. And then the older crew kind of died out and that was it.”

The buildings of these once-lively communities are going up for sale, and in a time with a serious housing shortage, many of them will simply be bulldozed and the land used for other purposes. In rural areas with less demand for real estate, the properties may just be left empty to slowly fall apart.

Catholics are in a unique spot, having to build bigger and more churches, like my own in Hillsborough, as numbers swell from immigrants from Latin America and transplants from northern states. But the national trends shouldn’t make Catholics any more comfortable.

Also, as the area becomes more uniformly secular and progressive, some of our neighbors in Orange County are making clear they aren’t really happy about our presence anyway.

Is the end of church so bad though?

This shift away from Christianity didn’t happen for no reason. And many of those who abandoned the faith of their family or culture (for what may be very valid reasons), are not shy about saying, “Good,” when they see these stats.

But before we convert all the chapels into loft apartments (or skate parks like can be seen below in a former Gothic-style St. Louis church), what if we take a moment to think about what role these odd gathering spaces full of singing and sermons played for our country. We owe our ancestors, who often poured much of their life and labor into those buildings, that much at least.

The American founders were an eclectic bunch when it came to faith. There were many faithful Christians (largely congregationalist and Anglican), but there were also many deists and other non-conformists. Below is Benjamin Franklin’s description of his own religious faith, which attempted to pull the core from all major faiths:

“Here is my Creed. I believe in one God, Creator of the Universe. That he governs it by his Providence. That he ought to be worshipped. That the most acceptable Service we render to him is doing good to his other Children. That the soul of Man is immortal, and will be treated with Justice in another Life respecting its Conduct in this. These I take to be the fundamental Principles of all sound Religion.”

But this diversity and eclecticism among the founders doesn’t mean they thought religion was an unimportant element of public life that should be kept private. On the contrary; second U.S. President John Adams even put it as strongly as to say, “Our constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

Liberty is delicate. Those who don’t appreciate its historical scarcity and value are likely to lose it by carelessness. Consider how a very responsible adolescent and a reckless one might deal with a lack of rules — one might build a business, the other might crash their car in a street race. The founders warned that if democracy was simply individuals pursuing their own interests, history shows they’d quickly turn into a violent mob. Instead, they envisioned a republicanism where voluntary institutions teach virtues that bind the population to causes and groups beyond themselves.

As long as these institutions lasted, the Republic and the liberty it preserved would be safe. This balance is often called “ordered liberty.” Twentieth century conservative icon Russell Kirk described ordered liberty as the permanent tension between individual freedom and the order of “the permanent things,” like religion, virtue, and Natural Law.

Edmund Burke was a contemporary of the founders and shared their goal of ordered liberty, despite writing from England. He responded to the less-ordered French Revolution by saying:

“I should therefore suspend my congratulations on the new liberty of France, until I was informed how it had been combined with government; with public force; with the discipline and obedience of armies; with the collection of an effective and well-distributed revenue; with morality and religion; with the solidity of property; with peace and order; with civil and social manners. All these (in their way) are good things too; and, without them, liberty is not a benefit whilst it lasts, and is not likely to continue long. The effect of liberty to individuals is that they may do what they please: we ought to see what it will please them to do, before we risk congratulations, which may be soon turned into complaints.”

There was a clear fear among more American-style republicans of the day about the “leveling” influence in the more French version of republicanism. Looking at France, they feared that by eliminating the traditional institutions, such as the church, all people would be leveled out, without regard to their accomplishments, positions, roles, abilities, or other distinctions (a dynamic not too different than modern progressives’ vision of “equity”).

This is my fear in the collapse in religion here in North Carolina and across the country. Philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, in his classic “After Virtue,” argued that without a common understanding of ethics, which had been provided by Natural Law and accepted by those of many religions and worldviews, we were descending into what he called “emotivism.”

In emotivism, the person no longer attempts to connect their beliefs and actions to a shared reality of Truth, Beauty, and Goodness with others, as Natural Law does, but instead bases them on their personal intuitions and emotions. But MacIntyre warns that this leads to the end of the ability to discuss important things like ethics and policy, because “saying, ‘I disapprove of this; do so as well,’ does not have the same force as saying ‘That is bad!'”

And this seems like the path we are quickly going down. In the 2020 book “Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World,” Tara Isabella Burton shows that the freefall of traditional religion has not led to the rational, atheist utopia Richard Dawkins may have envisioned. Instead, she says Americans are finding new things to replace what had been provided by religion, things like transcendence, moral guidance, and community — maintaining spirituality without the bonds of religion.

But, as the book title suggests, many of the most popular new practices are contradictory, superstitious, and strange, including neo-paganism, polyamorist cults, social justice activism, fanatical exercise groups, and sci-fi fandom. Most of these aren’t religions by themselves, but are ways to fill in the hole left by religion, bit by bit. But her research suggested these weren’t getting the job done.

The common link with it all is that individuals are increasingly feeling completely unbounded from any sort of moral accountability, tradition, or in-person community, and instead are spending more time in online spaces or in practices that position each individual as a sort of high priest of their own custom religion.

And as MacIntyre feared, this is often done based on what feels right to the intuition and emotions, rather than through a close examination of the truth claims in these beliefs and practices.

A secular future would be less free and more chaotic

And what would North Carolina be like if each home becomes its own temple with its own high priest? I argue, along with the founders and Burke, it will likely be ungovernable. Pluralism is hard enough with worldviews similar enough that they can be summarized as Ben Franklin did. But if each temple is directed towards the worship of the self — which a worldview based on individual whims is — then there will be no peace to be had other than the leveling Burke feared.

All worldviews, behaviors, truth claims, and values would need to be equally respected (no matter how ridiculous or egregious). In a leveled nation with a universal high priesthood, the only heresy would be to suggest that anybody else’s emotivist temple was worshiping a false idol or encouraging a false belief. This looks very much like the “dictatorship of relativism” that Pope Benedict XVI warned about. Telling a male who identifies as graygender that you do not agree that that is what he is, for example, would be serious blasphemy. Modern institutions seem to be enforcing this new worldview and its dogmas.

But we cannot live in a world where each person lives by a different set of assumptions about reality. Natural Law gave us all at least a common ground to work from, as did the American creed that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.” Without being able to at least accept those common foundations, we only have the chaos of the French Reign of Terror to look forward to, where each high priest gets to condemn everybody else for blaspheming their one true faith. The democracy of the mob will keep the guillotine rising and falling until all is leveled, maybe just executing reputations for a while, but unlikely to stop there.

Churches, with their hierarchies, moral lessons, shared community, and belief in the transcendent, were able to hold this chaos at bay. There’s no reason to believe we can knock out a load-bearing wall of that importance from our social structure and still maintain what we have. There also don’t seem to be any viable alternatives to the American church on the horizon that can pass on timeless norms. Workplaces and online communities hardly fit the bill.

But we can each fight back by shaking ourselves awake and seeing ourselves not just as an individual being serviced by big government and big corporations, but as a member of valuable civil associations (families, clubs, churches, communities). Free assembly of persons often seems like the least acknowledged of the First Amendment Rights. But in an age where we are increasingly atomized and isolated, we should pay special attention to it. It may be much harder to rebuild these assemblies, including viable temples to a deity worthy of worship, once they are closed, than it would be to maintain or reform what we have.