The push for electric vehicles in North Carolina and across the country may be the step that broke the “power grid’s back,” according to a new report.

According to the report’s author, Teri Viswanath, an economist with financial services company CoBank, the U.S. electric grid is now experiencing something of a mid-life crisis and isn’t ready for an onslaught of electric vehicles. The report indicates that most of the grid may be entering the end of its functionality. It was designed and built at a time when the thoughts of electric vehicles were just that, thoughts.

She said among consumer technologies or devices that will impact our future grid, electric vehicles stand out as the most disruptive.

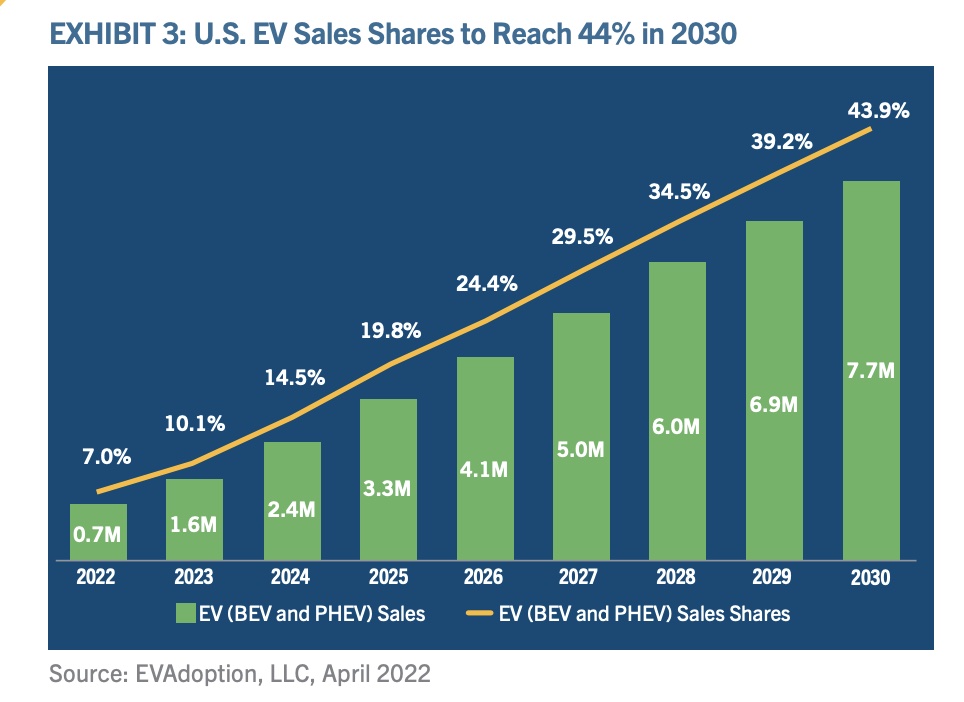

EV purchases are happening faster than expected in the U.S. Two years ago, Viswanath said it was projected that 10% of new cars by 2025 would be electric. In 2022, EVs already accounted for roughly 7% of new car sales.

Power outages have increased, up 64% this decade compared to the previous decade, according to the report. Age, weather, and the generating resource mix are undermining the U.S. power systems faster than the infrastructure can be replaced, reinforced, and possibly re-envisioned.

One doesn’t have to look any further than the loss of power many North Carolinians experienced over the Christmas holidays due to Duke Energy’s rolling blackouts.

Julie Janson, Executive Vice President and CEO, of Duke Energy Carolinas, said at a Jan. 3 hearing before the North Carolina Utilities Commission that the rotating outages were necessary to protect the integrity of the grid and mitigate the risk of serious failure affecting a more significant number of customers for more extended time frames.

High winds had already left 300,000 without power during the day of Dec. 23 before a severe cold snap later that night and into Dec. 24. Company officials called the weather combination “unique,” saying they used rolling blackouts for the first time in the utility company’s history.

Duke Energy’s “nuclear fleet” was reliable during the storm, according to Preston Gillespie, Duke Energy’s executive vice president and chief generation officer. Still, he said, in a few cases, insulation and heat tracing did not prevent instrumentation lines from freezing which caused a reduction in generation.

He also said that solar generation performed as expected but was not available to meet the peak demand since the peak occurred before sunrise. This problem is concerning if another outage occurs during high demand periods that include several cloudy days.

Viswanath said in her report that to bridge the gap, upstream grid operators are increasingly turning to large customers to voluntarily curb their power use during periods of high demand in order to keep the lights on.

A comparison was made between how much energy the transportation sector uses versus the electricity sector.

Currently, the transportation sector consumes roughly 27 quadrillion BTUs of energy annually, primarily from petroleum. In comparison, the electricity sector uses 37 quads total annually to supply electricity to end users in the U.S., including 24 quads of electrical system energy losses.

Viswanath said the impact could be enormous as the energy required for transportation shifts from fossil fuels to renewables and more significant distributed energy resources are put to use.

A study in the report shows that most people who own electric vehicles charge them at home around 8 pm, creating a significant system load among other residential, commercial, and mixed-use.

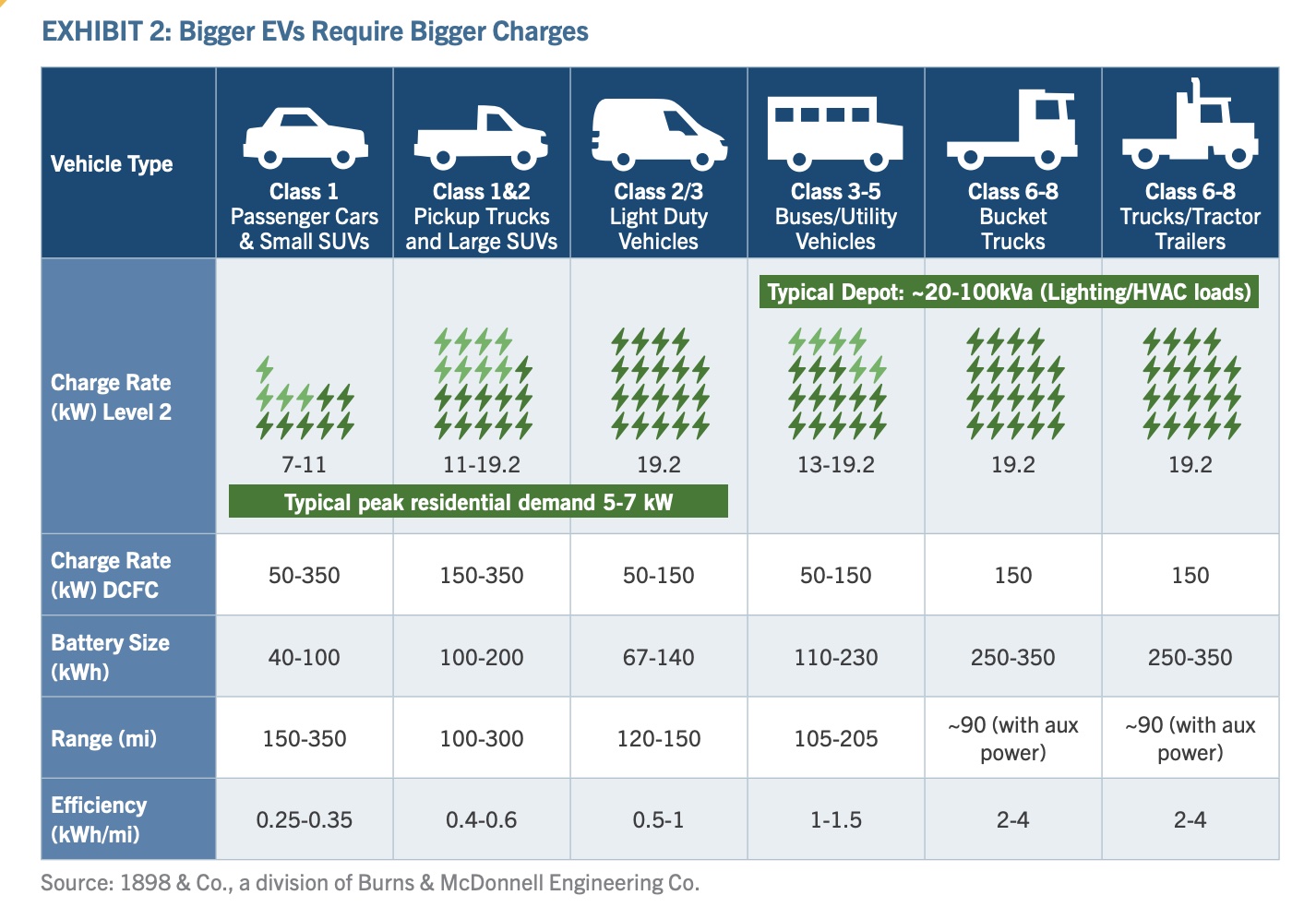

The timing of people charging their vehicles, combined with a group of bigger EVs, like a Chevrolet Silverado or Ford F-150, could pose, as Viswanath says, “a major threat to local distribution networks.” She cites a Department of Energy study comparing EV chargers’ power draws to various household appliances. Charging at home on a 240-volt level 2 charger will draw about 7,200 watts or less; a typical electric furnace draws about 10,000 watts, and a water heater uses 4,500. The charging requirements of light-duty trucks and heavier vehicles would increase a household’s electricity demand by 11,500 watts to possibly 19,200 watts.

As a start, Viswanath proposes more awareness to consumers on their energy usage as studies confirm many do not know the amount of energy they use or that charging a vehicle at a different time of the day might offer some relief to the power grid.

Still, she says, “Electric vehicle adoption could prove to be either the greatest grid disruptor or possibly the most effective grid-balancing tool. Where EV technology impacts ultimately land will likely boil down to the effectiveness of advance planning efforts and agile member communications.”