A performance audit released Thursday by North Carolina State Auditor Beth Wood’s office regarding the North Carolina Medical Board raises concerns for patient safety across the state.

Auditors were denied access by the board to the investigative records and supporting documentation necessary to obtain evidence to perform an audit from July 1, 2019, through June 30, 2021. They couldn’t determine whether NCMB’s investigations were completed in accordance with state law, board policies, and regulatory best practices.

As a result, Wood’s office says legislators and the public do not know how well the board’s investigative process protected North Carolinians from harm, such as malpractice, and inappropriate behavior, such as sexual assault.

“We were absolutely prohibited from being able to tell the General Assembly and the governor and the public that doctors who are a threat to the citizens of North Carolina and the people they serve and take care of that there is no way to tell if those who are a threat are being adequately investigated and disciplined,” Wood told Carolina Journal Thursday in a phone interview.

The audit’s objective was to answer questions like if the board reviewed all complaints it received against physicians, physician assistants, and other medical providers to determine if they warranted further investigation. Did the board complete investigations of medical providers it received complaints against within the six-month timeframe required by state law? And, did they report all of its public actions on the board website and do so in a timely manner?

Auditors could not test all 4,432 board investigations that occurred during the period. This occurred because the board denied auditors access to its investigative database, ThoughtSpan, citing state law, which states that all information related to board investigations is to remain confidential and not subject to release except in limited circumstances.

Wood’s office stated that this is untrue and cited state law, N.C.G.S. § 147-64.7(a)(1), which says the auditor’s office shall have access to persons and may examine and copy all books, records, reports, vouchers, correspondence, files, personnel files, investments, and any other documentation of any state agency.

The law also says the information obtained and used by the Office of the State Auditor (OSA) during an audit is confidential, which would have included the information requested by OSA for this audit.

The board did, however, discuss with auditors the possibility of providing access to ThoughtSpan if auditors acted as the board’s consultant.

Wood said entering into a consulting agreement such as this would have violated auditor independence as required by professional auditing standards and state law.

Instead, the board provided heavily redacted documents in response to auditor requests, including the name, license number, and contact information of the medical provider, investigation case number, and all medical records and interview notes used by the board during its investigations.

Auditors were, however, able to perform limited audit procedures on board investigations that resulted in public actions.

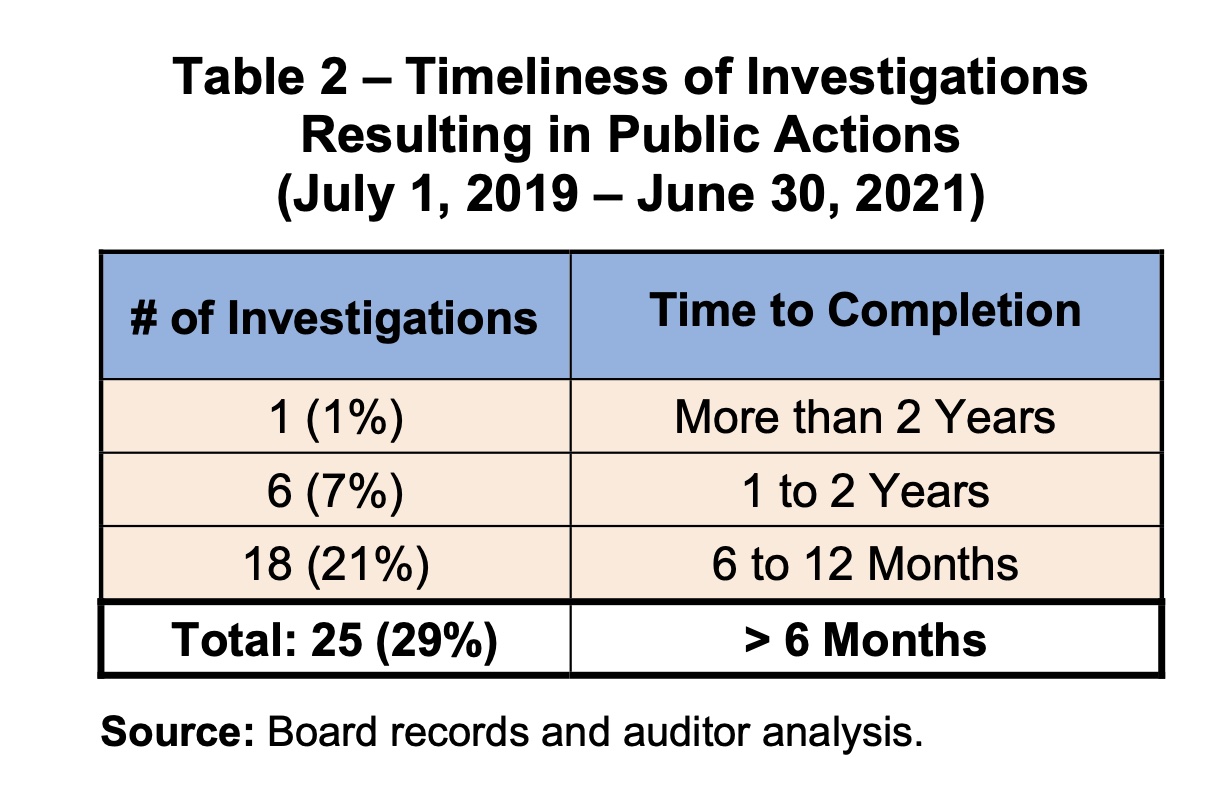

They tested the timeliness of 85 of 218 (39%) board investigations. Auditors found that the board did not complete 25 of the 85 (29%) investigations within six months as required by state law. They also found that the board did not monitor and enforce all disciplinary actions it imposed on medical providers. As a result, there was an increased risk that medical providers whose actions threatened patient safety could continue serving patients.

In one example, the board prohibited Provider A from treating patients after finding evidence that his treatment of two pregnant patients “failed to conform to the standards of acceptable and prevailing medical practice.” One patient and her newborn were subsequently hospitalized with multiple complications.

Additionally, Provider A admitted he had failed to conform to previous license limitations from 2015.

Auditors determined that as of June 2022, Provider A continued to maintain a website advertising his medical practice, including a recent patient testimonial and an active phone number.

Auditors also found examples of providers licensed to practice in North Carolina that were disciplined by other state medical boards. The North Carolina Medical Practice Act grants the board the power to discipline providers that were disciplined in other states to help protect North Carolinians, known as reciprocal actions. However, the board delayed or took no reciprocal public actions against these providers.

This isn’t the first time there have been issues with an audit of the board. A February 2021 audit found that several providers continued to serve Medicaid beneficiaries and receive payment from the state despite adverse actions from the board, such as license suspensions or revocations, that should have prevented them from doing so.

Wood’s recommendations for the board include allowing the Office of the State Auditor unrestricted access to all records and supporting documentation necessary to conduct an audit in accordance with state law and professional auditing standards.

Also, the North Carolina General Assembly should consider inserting clarifying language or specifically exempting the Office of the State Auditor from state law that restricts access to medical board records.

In addition, the board should complete all investigations of medical providers within the six-month timeframe required by state law, and it should monitor and enforce disciplinary actions against medical providers for the maximum protection of public health and safety.

R. David Henderson, NCMB chief executive officer, responded to the audit by saying they disagreed with several of the findings.

“Our organization is concerned that some of OSA’s findings and recommendations misstate the requirements of state law and, as such, find fault with NCMB for complying with its statutory obligations,” he said.

Wood’s office said that NCMB “made numerous inaccurate and potentially misleading statements” in their response, including OSA’s request for changes to the law to allow access to NCMB records ignores federal law that otherwise prohibits OSA’s access to private health information. The auditor’s office says it’s not true and that they are allowed access to private health information during their audits on a regular basis.

NCMB also said the auditor’s office mistakenly states that North Carolina law requires investigations to conclude within six months, which Wood’s office says is true unless a written explanation is provided for why a longer investigation is needed.

“If you are the protector of the health and safety as the medical board, you would want to get these done in six months or less, so to interpret it that we can take as long as we want?” Wood told Carolina Journal. “No, that is not the way the law reads and that is not the spirit of the law but again, it’s them spinning things because they’ve pretty much been caught with their pants down.”

Henderson’s response also said they would explore hiring an independent firm to perform their own audit.

If the NCMB doesn’t grant full access, including if after the General Assembly would clarify the law that gives the auditor’s office access, Wood said she would subpoena the information and go to court.

If the public is concerned about the report, Wood urges them to contact their legislators and ask them to look at the clarification of the law.