A decision last year by the N.C. Supreme Court ordering the state to compensate fairly property owners who filed a lawsuit over the Map Act appeared to signal a win for all people living in planned highway corridors throughout North Carolina, most notably a proposed beltline around Winston-Salem.

But now — more than a year after the June 2016 decision — the property owners who signed on to the lawsuit remain frustrated, angry, and unpaid.

The high court’s ruling came as a result of some nearly 500 lawsuits from North Carolina residents who cried foul over provisions of the act, enacted by the General Assembly in 1987. The act cleared the way for the DOT to file a highway corridor map locally and, consequently, prohibited governments from issuing building permits and stopped owners from subdividing property within the corridor.

So the property owners waited for relief. They waited some more, yet no compensation was forthcoming.

A long-time corporate client of Winston-Salem attorney Matthew Bryant told the lawyer something was amiss. That the playing field was skewed.

“We were playing by the rules as we understood them without questioning them,” Bryant said. “When called them on some things in 2009, the answers coming back from the department didn’t make any sense to us. It fell on my desk, and I basically said I think it’s unconstitutional that you tell people they can’t use their property. If I have a right to use it, I can use it. It’s not like a zoning question. I’m zoned perfectly legal to do what I’m doing.”

Bryant and his partners began aggressively looking at the issue in 2009.

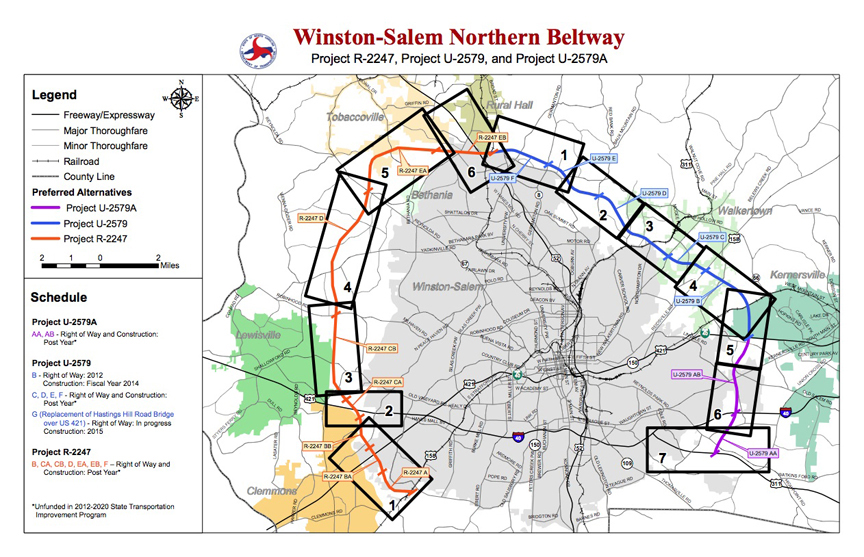

“We were told to go out in early 2010 and find people who were in the beltway that might be interested in suing. We really had no firm grasp of the scope of the frustration, the animosity, the distrust and the damage the department had done across the entire scope of the beltway. From that, one client here and one client there, and pretty soon you have 300, 400 clients across the state. … It really highlights that, if you don’t do anything, the state’s just going to roll over you like a freight train.”

The question is: Did that train keep on a rolling or is the DOT doing its level best to stand on the brake and fairly pay the property owners while remaining fine stewards of taxpayer dollars?

The courts, as an outcome of the Supreme Court decision, set a timetable for the DOT to complete appraisals and begin making deposits to property owners within highway corridors under the Map Act. But in late December 2016, the N.C. Court of Appeals, at the request of the DOT, blocked that order by issuing a temporary stay until an appeal could be heard.

The DOT says it’s working with property owners and have negotiated multiple settlements outside of the lawsuits. But the differences among each piece of property — as well as the properties’ inherent uniqueness and the varied guidance from district courts — affects greatly each individual compensation package. It’s virtually impossible, the DOT says, to throw a blanket over the litigants and simply start issuing checks.

The state’s response does little to satisfy Bryant.

“They haven’t given the appraisals to us for the taking they did. They haven’t won a hearing yet,” he said.

The DOT is looking at 470 cases, all specific to the geography of the particular case, says Chuck Watts, N.C. DOT general counsel. He came on with the new administration earlier this year.

“Whatever happened before I got here I really can’t talk about, but my orientation and goal on this has been to try to resolve these cases. Clearly, the property owners, some of them have been injured, and the state has an obligation to pay them. The question is, What’s the fair payment, and you have to be fair to both taxpayers and property owners. To try to draw that line is what’s difficult, because the Supreme Court, while they indicated there was a cause of action here, did not provide any further guidance as to the nature of the taking, the impact of a proportion of property being taken, any of that. So, we don’t really have what I call rules of the road yet to resolve it.”

The range of outcomes for any particular property goes from zero to a high number, he said.

“The plaintiffs’ attorneys,” Watts said, “are concerned about one thing and one thing only, and that’s maximizing the return for their clients. I’m a public servant. My whole career has been about trying to bring people together to try to resolve claims within the law.”

Bryant and his clients see things differently. He represents more than 300 parties in the lawsuits, which encompass seven counties.

“The state stubbornly stuck to its guns until the Supreme Court said the Map Act was a taking, and the legislature’s reaction has been to hire more lawyers, pay more legal fees, try to take away the interest these owners would be entitled to and have the maps rescinded.”

He compared it to being shot and left on a street for dead. “It doesn’t do you any good to say that they’re outlawing handguns.”

“Instead of honoring a constitutional obligation, they fund more attorneys to fight people’s rights to be paid fairly.”

He wants the state to begin compensating property owners as part of the lawsuit and court ruling. As the properties sit without upgrades or other renovations, common sense says their respect values will only continue to drop.

“They get the benefit of their bargain. In the tax cases they have to refund money; they don’t get anything back for that. So, we’re puzzled why people think this is some type of anomalous expense for the state. They’re getting a bargain here. They’ve got unimproved property without apartment buildings or shopping centers on it. They just have to pay for it and take the property. Very simple.”