The State of North Carolina is the sole shareholder of a 317-mile rail corridor, winding from Charlotte to the Port of Morehead City, known as the North Carolina Railroad Company (NCRR).

That is the short answer, to be sure; the whole story of how NCRR came to be is a tale of North Carolina history, political controversy, and state-sponsored economic development.

State of Change

While economic accolades for North Carolina are abundant these days – e.g., ranked as the Best State for Business by CNBC for two years running – those honors were much harder to come by in the 1840-50s. Back then, North Carolina was known as the “Rip Van Winkle State” because of its reputation for snoozing while neighboring states like South Carolina and Virginia seized upon economic opportunities.

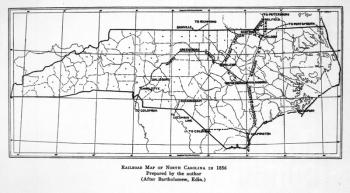

Intent upon waking up from this slumber, in 1848, the North Carolina General Assembly passed legislation authorizing a railroad connecting the Coastal Plain with the Piedmont. The charter (1849) called for the railway to extend “from the Wilmington and Raleigh Railroad where the same passes over the Neuse River in the county of Wayne, via Raleigh, and thence by the most practical route, Salisbury, in the county of Rowan, to the town of Charlotte in the county of Mecklenburg.“

Passage of the 1848 North Carolina Railroad bill was not easy. Our state’s current urban/rural divide may be mild in comparison to the stark division of interests between the eastern and western parts of the state in those times. Passage came down to a slim margin of approval in the NC House and an even slimmer margin in the NC Senate – one vote. That one vote ended the political career of Senator Calvin Graves; the proposed corridor did not run through his district, and the influential Democrat thereafter was never again elected to political office.

The structure of the railroad legislation set up what we refer to today as a public-private partnership. Other private railways existed on north-south corridors, but NCRR proponents aimed to connect the whole state, east to west, to truly enable development of an intra-state economy. The bill allocated $2 million from the state to purchase stock on the condition that $1 million be raised via stock sales to private citizens. Graves, former Governor John Motley Morehead, and others toured the state to pitch investors on an investment they hoped would bring North Carolina into the modern age.

While the official charter of NCRR routes it from Charlotte to Goldsboro, the NC General Assembly also incorporated in 1852 the Atlantic & North Carolina Railroad. This line, spearheaded by NCRR President and former Governor John Motley Morehead, connected Goldsboro to a 600-acre peninsula suitable for a coastal port called Shephard’s Point in Carteret County. The resulting planned community was named Morehead City. (NCRR and A&NCRR merged officially in 1989)

By 1850, the capital was raised, and the North Carolina Railroad Company was born. Construction began in 1852 (from Goldsboro in the east and Charlotte in the west), and after appealing to the legislature for an additional $1 million due to construction cost overruns, the North Carolina Railroad opened in 1856.

Growth

With the railroad operational, financial success came quickly. Revenue increased each year, and along with it, government revenue, as the state was the largest stockholder (75% of outstanding shares). This burgeoning commercial activity gave rise to towns most of us are familiar with: Burlington, a midway point at which NCRR established its company shops, Thomasville, Mebane, High Point, Durham, Clayton, Selma, and even Morehead City.

The rail connections were a boon for expanded trade. As farmers imported new fertilizers, crop yields in wheat, cotton, and tobacco took off. Newly established towns like Durham and High Point became hubs of the tobacco and textile industries, and heretofore, unprofitable markets for crops and materials were opened up to opportunistic producers and entrepreneurs.

Indeed, North Carolina flourished commercially during this period, shaking off the sleepy Rip Van Winkle label and beginning to stand on an invigorated economic footing until the advent of the Civil War. While tracks and infrastructure suffered disrepair and outright destruction during the War, railroad traffic itself increased markedly. By 1867, damages were repaired, and new equipment was purchased, a valuable asset for North Carolina to leverage during Reconstruction and into the 20th century.

Operation & Ownership

While building a railroad to connect the Old North State proved critical for economic development, keeping the trains running on time may have been less attractive. Perhaps spurred as well by natural suspicions around which connected politicians may have been unduly benefiting from the NCRR’s quasi-governmental creation, the Company signed a 30-year lease for Richmond and Danville Railroad (R&DRR) to take over operations and equipment on the corridor. R&DRR was later acquired by Southern Railway (now Norfolk Southern), a J.P. Morgan venture, in 1894, and a new 99-year lease was entered into.

The lease arrangements have changed a few times, each between NCRR and now Norfolk Southern, culminating in the current trackage agreements. Ever since, the NCRR has operated more as a real estate asset, leasing out exclusive freight service rights.

So, the bifurcated ownership structure that marked NCRR from its formation remained. That is, until 1998, when the State bought out the 25% of private stockholders, and NCRR became an only slightly less complicated entity: a privately-run business wholly owned by the State of North Carolina. At the time, NCRR was valued at $289 million.

Instead of cash dividend payments to shareholders (the State), the NC General Assembly passed legislation in 2000 enabling reinvesting those dividends into improving corridor infrastructure and maintenance. Yet, even in the 2000s, many lawmakers may have been surprised to learn the State owned a railroad. In 2012, curiosity ran over, and the state legislature directed the Program Evaluation Division (PED) of the General Assembly to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of NCRR, “a discretely reported component of the State of North Carolina, of which the State is sole shareholder.”

The report highlighted the historical, financial, and operational details of NCRR. It also made certain recommendations for the state to realize a better return on this convoluted partnership. In it, PED suggests NCRR has benefitted from its unique relationship with the State of North Carolina,” but that the State really hasn’t profited financially from the arrangement.

While the 2012 report observed the State is quite limited in its oversight of NCRR, owing to its status as a private corporation, it advised against selling NCRR or the corridor to private interests as “these valuable rail assets and their long-term earnings potential would be lost” to the state. Further recommendations included requiring a one-time dividend and annual dividend equal to 25% of income thereafter, strengthening reporting requirements for NCRR, and requiring them to sell non-essential properties with proceeds directed to the General Fund.

Next Stop?

In the decade since the program evaluation, an effort that presumably satisfied then-lawmakers’ curiosity about the railroad the state-owned, NCRR has continued its mission to maximize value across the corridor within which it operates.

Take a look at recent annual reports and you’ll find NCRR investments that track with the most notable economic development announcements over the past two years. It shows how State spending (taxpayer spending) on big economic developments “wins” like Vinfast and Toyota Battery is often more than meets the eye.

In NCRR’s 2022 annual report, the most recent available, NCRR lists an investment of $1 million toward the site of Vinfast’s Randolph County production facility, and a $35 million investment contributing toward the Greensboro-Randolph Megasite that will be home to Toyota’s new battery plant. The same report lists 2022 operating losses and net losses of $16,629,142 and $58,336,316, respectively.

Investments like these could make a lot of sense from the railroad’s perspective, but where the bottom line is isn’t exactly clear when considering NCRR’s ownership structure. Partnerships between public and private interests were not exactly unique when NCRR was formed and they are hardly rare in modern day. What is unusual, by NCRR’s admission, is the unique partnership of a privately owned corporation, whose stock is wholly owned by the State, that has endured for more than 150 years and grown to include the North Carolina Department of Transportation and other taxpayer-supported entities.

Where the next stop is for NCRR is a matter of inertia. It’s hard to stop a train, after all, especially one that’s been building momentum in this unique economic development arrangement for over a century. It must then rely on lawmakers’ willingness to again examine whether the State of North Carolina owning a railroad is what’s best for the People of North Carolina or if an evolution toward free market ownership of this historical uniquity might leave them better off?