In recent years, the push for more STEM courses in K-12 education has advanced alongside calls for entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurs like Steve Jobs, Jeff Bezos, and Elon Musk start new businesses that improve our quality of life and, perhaps more importantly to its political supporters, help the United States stay ahead of competitors abroad, particularly in China, so entrepreneurship must be protected even if political policies do not always support new business formation. The iPhone, free, two-day shipping, and luxury electric sportscars have won over even the most hardened antibusiness progressives about the benefits of entrepreneurship.

Introduction

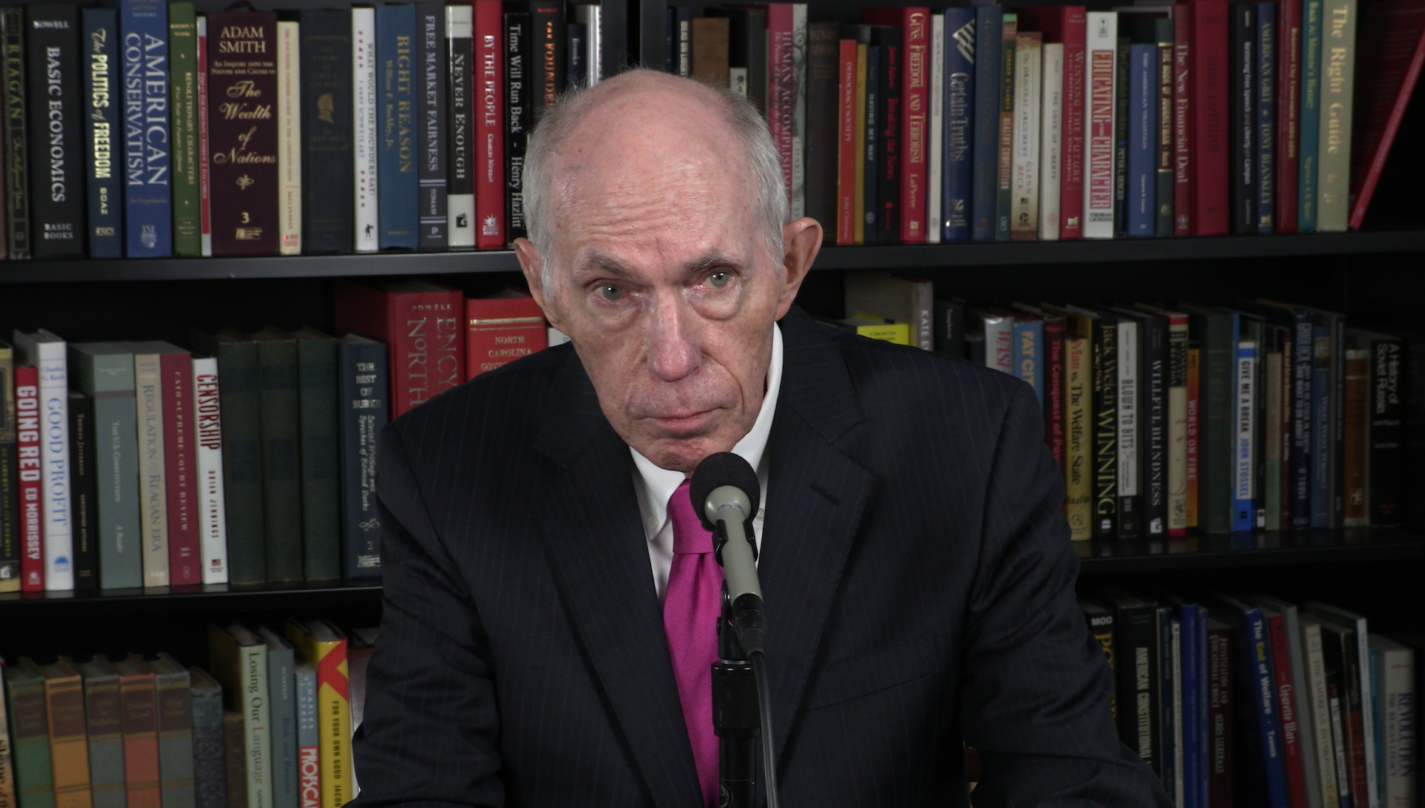

My time at Thales Academy, a private, classical school in Raleigh, North Carolina, has given me a unique perspective on entrepreneurship, quite different from that of entrepreneurship’s typical supporters.

Classical education is a brand founded on the great books and the great ideas of the Western canon. These ideas naturally support the ideals of entrepreneurship in a way few schools do. Even among other classical schools, a movement that has grown all the more popular post-covid, there is rarely the same emphasis on business formation: the focus is on the past and not necessarily on the future and ways of improving that future through hard work and new products.

Our founder, Bob Luddy, a philanthropist and the owner of a successful kitchen equipment and HVAC company, is himself passionate about entrepreneurship. He founded Thales Academy to pass the opportunities he enjoyed to the next generation and encourage students to believe that they can radically improve the world through sweat equity and quick thinking, something summed up by entrepreneurship.

Indeed, entrepreneurship provides a logical and thoughtful complement to classical education. Together, entrepreneurship and classical education are grounded in the values of the Western tradition, the individual rights and freedoms guaranteed in our founding documents, and the hope for a better future that both entrepreneurship and classical education nourish.

Entrepreneurship: Grounded in the Tradition

Simply put, an entrepreneur creates his or her own business and assumes the risks of building something from the ground up. The word is originally French, whereas, in English, the term used for this type of occupation is adventurer. After all, entrepreneurs were merchants traveling from their home ports of Tyre and Sidon, the merchant republics of Venice and Genoa, or the seaside wharves of London and Bristol, New York and Boston–to obtain goods unobtainable at home. Those risks increased with the length of the voyage, but so did the rewards.

For instance, many of the most prominent figures in American history were small business owners–Ben Franklin. Or, they tried to run a business but failed in the endeavor, only to pick themselves up and keep trying something new despite the setbacks, like Harry Truman.

Entrepreneurship’s opponents have deep roots in the tradition, too. Such opponents included those already in power or who had the “sharpest elbows” needed to game the system. To counter such influences, classical educators may defer to the Romans’ suspicion of kingship and monarchy; Adam Smith’s writings on the benefits of free enterprise, unencumbered from bureaucratic meddling; or Lord Acton’s oft-cited maxim on absolute power corrupting absolutely. But the end goal is ultimately the same as that of free market supporters: the best ideas come from individuals, not governments, so individuals should be free from bureaucratic hurdles to turn a better idea into a superior product or service for consumers.

Entrepreneurship and the Founding Documents

Part of what encourages a person to start their own business is the knowledge that someone with power, authority, and government connections cannot all-of-a-sudden come in and take the fruits of one’s labors, something that can happen in other countries with a less developed system of property rights or independent courts. Such ideals are at the core of the American experience. That’s why Thales, in particular, and classical schools, in general, champion America’s founding documents and principles. Such schools enshrine as a principle and as ideal, the natural right given to us by God to chart our course for happiness and human flourishing rather than being manipulated by other, more powerful individuals.

Our country is founded on the unique idea, one enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, that all men are created equal, and that they are endowed with their Creator with certain inalienable rights, chief amongst them is the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Similarly, the Constitution protects the right of individuals to earn revenue from their inventions.

Article I, Section 8: To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.

Our founding documents recognize that the individual, not the state, is in the best position to promote this kind of progress. Our Constitution, which as a document limits our federal government, limits the ability of anyone within the state and its bureaucracy to unfairly and unjustly seize the fruits of anyone else’s hard work.

This right is enshrined as a cherished privilege for American citizens. American citizens are all the more encouraged to start their own business to take care of themselves–a restaurant, a cleaning service, taking in and washing laundry, the story of so many people coming to the United States with barely the clothes on their back–rather than relying on the state for their daily bread. This nation is uniquely blessed to have, as its founding principle, a transcendent truth that, at once, inspires some people to endure untold sacrifices and, as part of its founding documents, a provision that keeps others from simply forcing them to do so.

Entrepreneurship: Fruits versus Force

Our founding documents, guided by the same traditions at the heart of classical education, stipulate that the fruits of one’s labors cannot and should not be unjustly seized from individuals. At times, the word fruits is replaced with profits, the money an entrepreneur makes by creating value in the marketplace. Tragedies that we have witnessed in the past five years in countries from Venezuala have come about because, for decades, government officials refused to let private industries and private individuals keep such profits they had earned from their hard work.

That alternative is indeed horrifying. The contrast between free enterprise and socialism is born out by comparing the American experience in Alaska with Russia’s settlement and development of its eastern regions.

Alaska saw a series of major gold rushes in places like Nome and Fairbanks, as well as the Klondike region of northwestern Canada, towards the end of the 19th century. Tens of thousands of settlers rushed to a land where winter temperatures dip below negative thirty degrees Fahrenheit and which receives as little as five hours of sunlight in the winter. Yet, settlers migrated across vast expanses of snowy wilderness for an opportunity and the reward that may accompany it. After all, whatever gold those settlers found, they could keep.

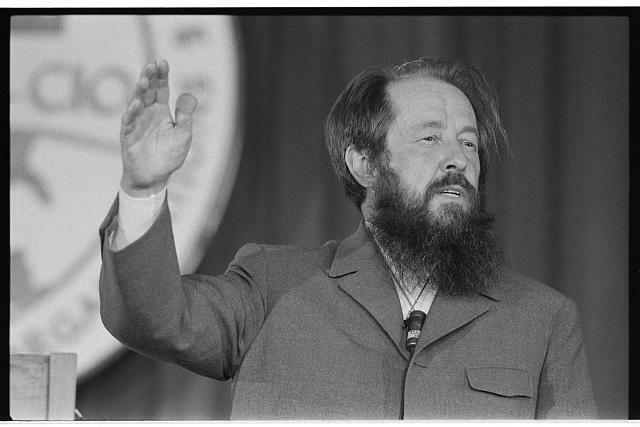

In contrast, consider the Gulag Archipelago, the system of forced labor camps across Russia and Siberia. The Gulag was set up to exploit Russia’s cold, eastern reaches. For decades, the Soviet Union arrested people in the tens of millions with the intention of transporting them to these camps to build railroads, dig canals, or toil in mines. Sure, the Bolsheviks and the Stalinists imprisoned political dissidents who spoke out against the regime. Still, on principle, these Communists were unwilling to let people keep any kind of reward for their labor. Such rewards reeked of capitalism’s incentive system that lies at the heart of entrepreneurship. Knowing they still had to develop their lands and vast natural resources, communist leaders forcibly transported tens of millions of people to develop Russia’s untold natural wealth. How else was Stalin going to complete his five-year plan?

A state founded on Marxist principles loathed the idea that all people are created equal. From this, they performed acts of unfashionable cruelty, an experience well-documented in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s “The Gulag Archipelago.” In contrast, a country like the U.S. could develop a region as cold and windswept as that of Russia east of the Urals without resorting to force and coercion. Those tens of millions of settlers were guided by the practical concerns that gold fetched a high price and the transcendent hope that a better future lay just beyond the horizon.

Conclusion

At heart, entrepreneurs share one thing in common: they have an idea and seek to transform that idea into a reality so the business can succeed. If the business is successful, they reap the rewards of taking the risk and pouring something called “sweat equity” into their venture.

We have seen this trend on full display during the pandemic when government-imposed lockdowns and restrictions to curb the spread of covid-19 saw an untold number of businesses being asked to shut down and put their livelihoods on hold. Yet, despite these hurdles, the Bureau for Labor Statistics reported that 2020 saw the largest increase in applications for new businesses being filed, something on the order of 5.4 million applications.

To supporters of free-market economics, we hope this trend will continue, a trend that hardly anyone could have predicted in March 2020. Those who teach in classical schools, we hope to help our students develop the same mindset of solving problems and contributing to society by developing their gifts and talents to the best possible extent. Otherwise, who knows how we might weather the challenges of an unknown and uncertain future?

My own school is an outgrowth of the success of one firm and our founder’s heart to help the next generation take advantage of similar opportunities and risks. That is ultimately the mission of Thales Academy in particular and of classical schools in general: to help students become people of excellence through truth, beauty, and goodness, an excellence marked by personal responsibility and innovative problem-solving. Those principles are so often reflected by the ideas and ideals of entrepreneurship.

Winston Brady is the director of curriculum and Thales Press at Thales Academy, a network of classical schools with campuses in North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and South Carolina.

A graduate of the College of William & Mary, Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, and the Kenan-Flagler School of Business at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Winston writes on the intersection of history, politics, and culture, as seen through the lens of classical wisdom and virtue. He lives in Wake Forest with his wife Rachel of 10 years and his three boys, Hunter, Jack, and Samuel, all of whom will one day learn Latin.