National conservatives understand better than most that many in our modern civilization feel uprooted and adrift. Their attempt to address the malaise of modernity gives them broader political support than is warranted. In the end, they do not apprehend the roots of the modern political crisis, and their suggested solutions would undoubtedly deepen the social discontent they aim to solve. In a previous essay, I endeavored to display the ways in which national conservatism undermines the American constitutional tradition, but perhaps even more dangerous is the way the movement seeks to shatter the social basis of a flourishing liberal society.

The liberal tradition has always had two strains. The first is the statist liberal tradition which originated in the radical moments of the French Revolution. The driving force of statist liberalism is the idea that human progress can only ever be brought about by powerful state intervention in our lives. For an example of such liberalism, one need only look to the modern attempts by some on the left to regulate every facet of American life.

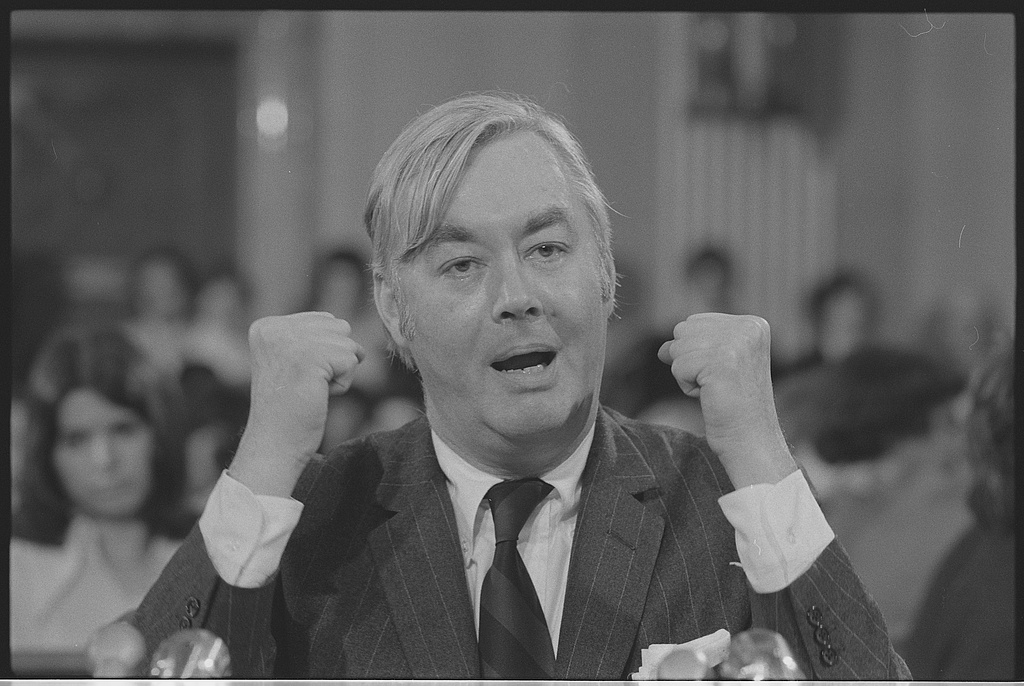

The statist tradition can be contrasted with a pluralist strain that emphasizes the importance of communities and civil associations as the key to unlocking human flourishing. In this view, human happiness is best achieved not through the state but through local institutions such as colleges, town halls, hospitals, and so on. This is the liberalism of Edmund Burke and Alexis De Tocqueville. Pluralist liberalism itself takes on two common forms. In the hands of men such as Milton Friedman, it adopts a libertarian nature, while other pluralist liberals such as Daniel Patrick Moynihan instead work to use government to empower and enliven what Burke called “the little platoons” of society.

The pluralist strain of liberalism in both its right and left-leaning forms is a species native to America. The American founders are some of the greatest proponents of pluralist liberalism, and it is in their writings, one can find some of the most beautiful articulations of this school of thought. After all, who cannot help but be moved by the eloquence of Jefferson’s writings on religious liberty or the scholarly firmness of Adams’ discourses on the constitutional arrangement? For the founders, the whole purpose of government was to empower smaller communities to thrive, whether by leaving to its own devices or political assistance. They understand that it is in local existence that mankind finds his greatest personal fulfillment. Not in an empire or nation.

The national conservative attack on America’s liberal tradition derives from an immature view of liberalism. Lacking the nuance to appreciate the possibility that there are various strains of liberalism, national conservatives think that all liberalism is statist. In their eyes, the attempt of the national government to remain above cultural and moral debates does not leave such issues to civil society. Instead, it forces upon the American people dangerous secularity. They cannot comprehend how liberalism does not inevitably devolve into state-mandated moral relativism.

To be fair to national conservatives, large swathes of the American left have been captured by statist liberals. However, in the face of this tragedy, national conservatives seek not to reverse statism but adopt it. For them, human flourishing is impossible without a strong government regulating everyday Americans’ lives. That they have different ends than statist liberals makes little difference, for their methods will continue the tragic erosion of the little platoons that make up our society. Though national conservatives decry the ways in which globalism has eroded localism, they seem recklessly unaware of the extent to which nationalism can do the exact same thing.

In short, national conservatives fail to appreciate the diversity and happiness of a society that is left to flourish at its local foundations. They also fail to imagine an alternative method to that deployed by their opponents. They wish to swap one form of statism for another and one idealistic vision that erodes localism for another. In many ways, the problem of national conservatism is a problem of imagination. They hate statist liberalism with such fervor that they fail to see beyond it to the beautiful society made possible when, at last, liberalism can be shaved of its contemporary nationalist and globalist dictatorial coats.

Jeffery Tyler Syck is a Ph.D. Candidate in American politics and political theory at the University of Virginia. He has had fellowships with the Bradley Foundation and UVA’s Karsh Institute of Democracy.