It has been nearly three years since the left-leaning Center for American Progress published a superb report, Return on Educational Investment: A District-by-District Evaluation of U.S. Educational Productivity. In the report, CAP Senior Fellow Ulrich Boser made the case that decades of significant funding increases for our public schools failed to produce lasting innovation or progress. Consequently, public school systems needed to cease thinking of inputs and outcomes separately and embrace the concept that unifies them: educational productivity.

Unfortunately, Americans have been conditioned to equate the quality of education with the condition of various inputs — per-student spending, educational technology, teacher pay, class size, school buildings, and the like. Presumably, schools will succeed so long as governments furnish high tech gadgets, pay teachers a lot, have small class sizes, and construct magnificent school buildings. But no matter how many times researchers find weak empirical relationships between spending and performance, the public will insist that schools are one teacher pay raise away from educational glory.

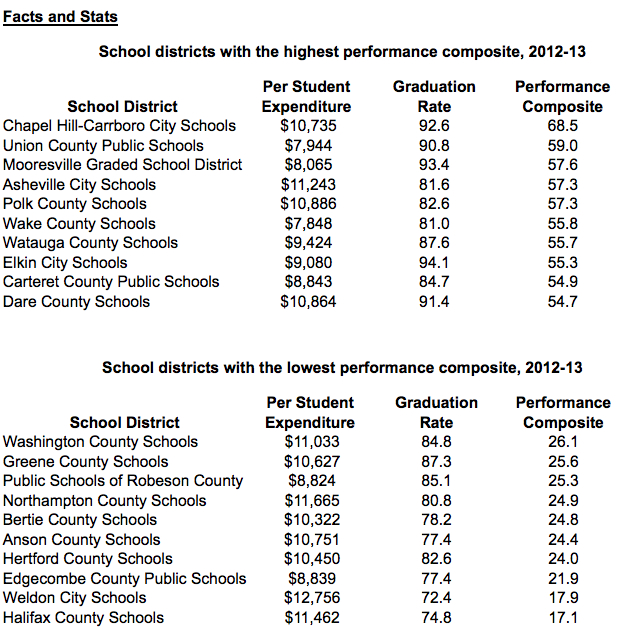

In the spirit (and lacking the sophistication) of Boser’s report, I examined N.C. Department of Public Instruction expenditure and student performance data for each of North Carolina’s 115 school districts. For the purpose of this column, I examined districts according to their “performance composite,” the overall passing rate for tests administered in each district last year.

While Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools had the highest performance composite, the district also spent significantly more per student ($10,735) than the state average ($8,514). Asheville City Schools and Polk County Schools were two other high-spending, high-performing districts.

Union County Schools, Mooresville Graded Schools, and Wake County Schools performed very well despite spending less per student than the state average. Arguably, these were the three most productive school districts in the state. To put it another way, Union, Mooresville, and Wake “got the most bang for the buck.”

Davidson County Schools, North Carolina’s lowest-spending district ($7,374 per student) had a respectable showing. Only 27 districts had a higher performance composite than Davidson. The state’s highest roller, Hyde County, spent $17,557 per student but had a middling passing rate, 37.3 percent.

Speaking of big spenders, a number of districts, mostly in the northeastern part of the state, spent considerably more than average but had difficulty raising student achievement. Northampton, Bertie, Anson, Hertford, Weldon City, and Halifax spent between $10,000 and $13,000 per student but had overall passing rates that fell below 25 percent.

(Download this PDF to see how every school district performs on this measure.)

Obviously, performance composites are one of many measures of student performance. Graduation rates, ACT scores, SAT scores, Workkeys results, and testing passing rates by grade and subgroup are a few of the many ways to measure student outcomes. Likewise, per-student expenditures are one of a number of inputs that may be employed.

Regardless of the variables used, we need to begin thinking about education reform in terms of productivity and returns on investment, concepts that, by the way, do not preclude conceptualizing education as a social good.

Dr. Terry Stoops is Director of Research and Education Studies for the John Locke Foundation.