Rep. Dennis Riddell (R-Alamance) recently filed an eminent-domain reform bill in the N.C. House of Representatives. This is a welcome development in many ways, and we should all be grateful to Rep. Riddell for getting the reform process started. However, if North Carolina is to catch up with our neighbors in terms of the protection of property rights, there is still a long way to go.

For readers who are not familiar with it, the phrase “eminent domain” refers to the government’s power to take private property without the owner’s permission. Throughout most of American history, it was generally assumed that this power could only be exercised when the property in question was needed by the government for its own use, e.g., for roads, military bases, and other government facilities, or for use by a “common carrier,” i.e., a private company like a railroad or utility that is obliged by law to serve the public.

It was also generally assumed that these restrictions were implicit in the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which states, “Nor shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation.” In 2005, however, when the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its opinion in Kelo v. City of New London, the American public was shocked to discover that both of those assumptions were wrong.

The controversy in the Kelo case began when an economic development plan approved by the city of New London, Connecticut, authorized a private developer to use eminent domain to take and demolish 15 well-maintained and well-loved homes. The developer would then build new offices, parking, and retail stores in their place. Led by Susette Kelo and represented by the Institute for Justice, the homeowners challenged the taking, arguing that, as a transfer from one private party to another, it exceeded the scope of the eminent domain power as defined by the Fifth Amendment.

The case received a great deal of media attention, and public sympathy was overwhelmingly on the side of the homeowners. Nevertheless, when it finally reached the U.S. Supreme Court, the court sided with the city. It held that, while the Takings Clause might forbid transfers from one private party to another “for the purpose of conferring a benefit on a particular private party,” it did not forbid such transfers when they served a “public purpose.” The court declared, moreover, that the question of whether this or any particular taking actually serves a public purpose is not one that the federal courts should attempt to answer. Instead, the courts should give state governments “broad latitude in determining what public needs justify the use of the takings power.”

In the final paragraph of its opinion, the court acknowledged “the hardship that condemnations may entail, notwithstanding the payment of just compensation,” and it invited eminent domain reform at the state level: “We emphasize that nothing in our opinion precludes any State from placing further restrictions on its exercise of the takings power.”

The decision was a bitter defeat for the homeowners, made more bitter still, no doubt, by the fact that — as is often the way with such projects — the proposed redevelopment of their former homesites never happened. The land remains vacant to this day, occupied only by a colony of feral cats. Nevertheless, in the end the homeowners had the satisfaction of knowing they hadn’t fought in vain. Their fight to defend their homes brought two serious, but previously little-known, problems to the attention of the American public:

- In the name of economic development, state and local governments across the country were using eminent domain to transfer property from ordinary citizens to politically connected developers and industrialists.

- The federal courts would do nothing to prevent such transfers.

In response to these revelations, states began to do exactly what the Supreme Court had invited them to do: they began to amend their own statutes and their own constitutions in ways that placed “further restrictions” on the use of eminent domain within their jurisdictions.

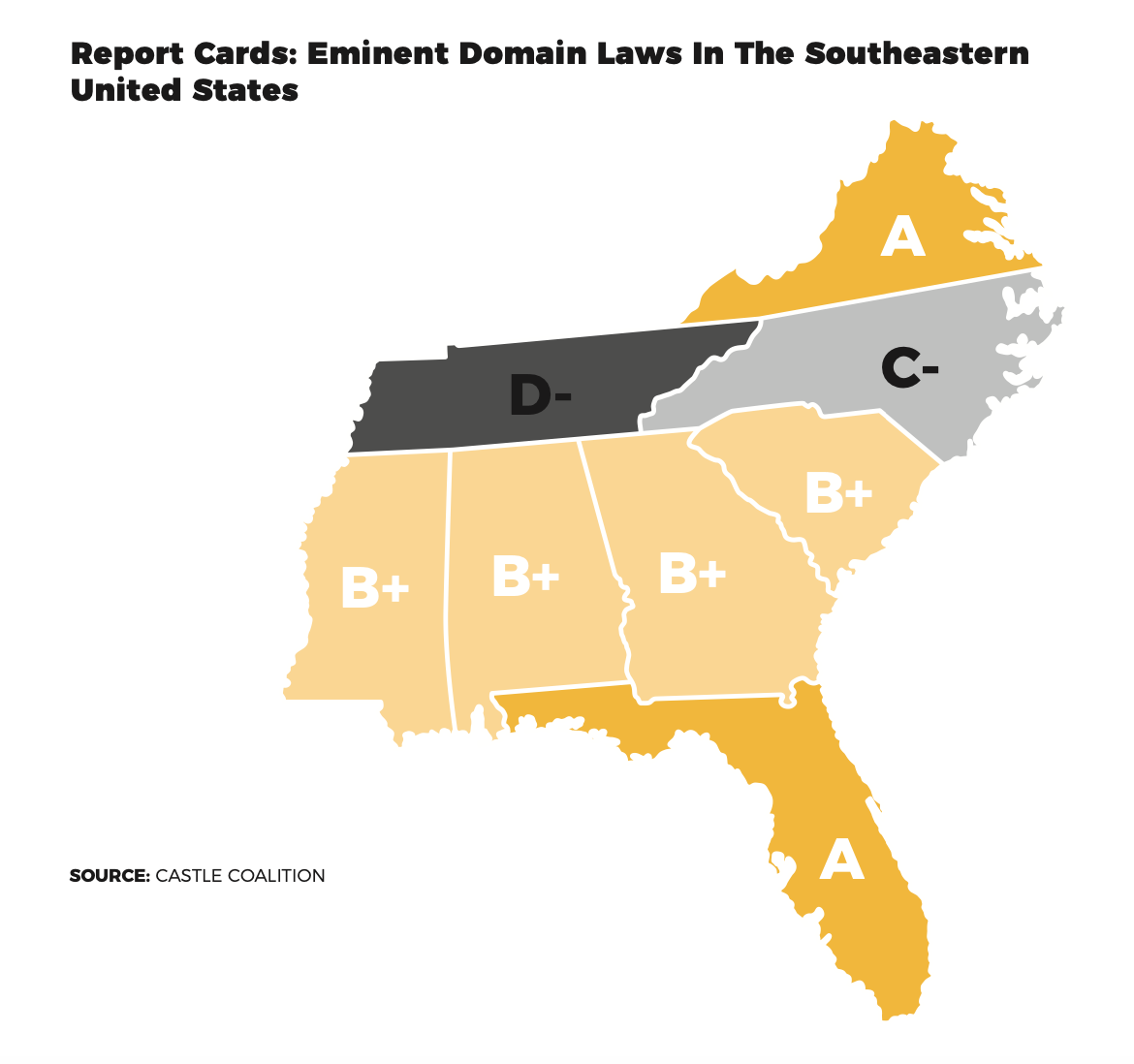

The southeastern states did particularly well in this regard. Almost every state in the region has put in place highly effective measures to prevent eminent domain abuse, and the measures put in place by Florida and Virginia are generally considered to the most effective in the entire country.

In both Florida and Virginia, the reform process began with the state legislature enacting statutory changes. Significantly, however, in both states, the voters later approved constitutional amendments that supplemented statutory protections with specific, constitutional restrictions on takings in which property is transferred from one private party to another for the sake of economic development.

Unfortunately, despite the persistent efforts of many members of the North Carolina House of Representatives, the North Carolina General Assembly still has not taken steps to protect North Carolinians from the kind of eminent-domain abuse the U.S. Supreme Court authorized in Kelo. It has not added suitable restrictions on the use of eminent domain to the North Carolina General Statutes, and it has not given voters an opportunity to add such restrictions to the North Carolina Constitution.

While large, bipartisan majorities in the North Carolina House of Representatives have passed eminent-domain reform bills in every long session since Kelo, no eminent-domain reform bill has been approved by the North Carolina Senate. As a result, when it comes to regulatory freedom, North Carolina languishes in the bottom half of states, both nationally and regionally.

Inevitable eminent-domain abuse arrives in N.C.

The massive incentive package awarded last year to Vietnamese carmaker VinFast shows just how much eminent domain reform is needed in North Carolina. Forcing our taxpayers and businesses to pay over $1 billion to support a foreign corporation is bad enough. Making it worse, however, is the fact that — as part of the deal — the state agreed to use its power of eminent domain to take dozens of homes, five businesses, and a church for roadway improvements and other infrastructure projects that it will build for VinFast at taxpayer expense. This is proof positive that North Carolina politicians and bureaucrats are prepared to trample on the rights of ordinary property owners in order to provide special benefits to favored business interests.

Thanks to Rep. Riddell, North Carolina has another chance to meet or exceed what neighboring states have done to protect the property rights of their citizens. Doing so will require the N.C. Senate to finally step up and approve a bill. It will also require amending the bill to include property rights protections like the ones that make the eminent domain laws in Florida and Virginia the best in the country. Florida’s eminent domain statute, for example, requires localities to wait 10 years before transferring land taken by eminent domain from one owner to another. Virginia’s constitution places the burden of proving “public use” on the government and defines public use in a way that explicitly excludes economic development.

Ideally, a bill will be approved that includes all the property-rights protections discussed in the Eminent Domain section of Locke’s “Policy Solutions” guide, including:

1. A definition of “public use” that forbids transfers from one private party to another for the sake of economic development and permits such transfers only when the property is needed by a common carrier or public utility to carry out its mission, or, in cases of blight, when the physical condition of the property poses an imminent threat to health or safety.

2. A statement to the effect that private property may be taken only for public use and only with just compensation.

3. A stipulation that courts must decide the question of whether a taking complies with the public-use requirement without deference to any legislative or administrative determination.

4. A definition of “just compensation” that ensures owners are made whole for all losses and costs, including loss of access, loss of business goodwill, relocation costs, and reasonable attorney’s fees.

We should be grateful to all the members of the N.C. House who have been working so diligently for so long to provide that protection. Let us hope they finally succeed in getting that protection enacted into law this year.