As President Biden faces mounting questions about his ability to lead and govern due to his age and declining health, historic North Carolina US Senate campaigns across three decades show the perils and pitfalls these issues present at the moment and throughout history.

1992

It was my first election as a voter — November 1992. I attended a rally just before Election Day with my mother in Durham for incumbent Democrat US Sen. Terry Sanford of Laurinburg. It was a sad day for my mother. She knew her former boss, mentor, and friend was headed for defeat. In part, if not mostly, because Sanford had a serious health scare at the worst time politically.

To us, Sanford was not a politician. He was family. Both of my parents had worked on his historic 1960 campaign for governor, defeating Isaac Beverly Lake Sr. in the Democrat primary runoff. Lake had campaigned on a racist, segregationist platform, which was popular in the Democratic party and in North Carolina, then a one political party state. However Sanford’s more moderate stances on race won the day, due to the strengths of organizing efforts by young Democrats across the state.

My mother became Gov. Sanford’s chief executive administrator. She handled his daily calendar and correspondence. When needed, she babysat Terry Sanford Jr and the other Sanford children. My father went on to work in the expanding community college system led by Dallas Herring, who I am honored to be named after.

As reported in the News and Observer on Dec. 28, 1963, while governor, Sanford skipped attending the 1963 Gator Bowl, featuring UNC Chapel Hill and Air Force, to attend my parents wedding and host their reception at the Executive Mansion.

According to Duke University, as governor of North Carolina from 1961 to 1965, Sanford focused on strengthening education, combating poverty, and expanding civil rights. During his tenure, state expenditures for public schools nearly doubled. He supported desegregation at a time when other Southern politicians were continuing to fight it.

Sanford was later recognized as one of the 10 best governors of the 20th century.

In 1970, Sanford began his 15-year tenure as president of Duke University, where he was widely credited with transforming the respected Southern campus into a world-class research institution.

1986

It was actually an acute health issue and death that opened the door for former Gov. Terry Sanford to return to elected office some two and a half decades after he last stood for election.

In 1980, Jesse Helms handpicked Republican John East, a wheelchair-bound ECU professor to run and defeat incumbent Democratic US Sen. Robert Morgan.

East defeated Morgan by just 0.6% (10,411) in still the closest US Senate election in North Carolina history. Yet East was plagued by health problems. The then-55-year-old East had been wheelchair bound since he was 24 and was afflicted with polio that led to his discharge from the Marines. East missed much of his legislative work in 1985 due to illness, opening the door to former-Gov. Terry Sanford announcing a bid for US Senate in 1986. East declined to run for re-election and committed suicide in the summer of 1986. East blamed his depression and bad health on poor medical care that did not diagnose debilitating thyroid disease.

In 1986, Sanford defeated former US Rep. and interim US Sen. Jim Broyhill 51% to 48%.

My mother exited the Governor’s Mansion along with Sanford at the end of his single term (the only one allowed at the time) at the end of 1964. She went on to teach in the public schools, retiring in 1991.

Sanford still had a commanding presence and appeared in great health when he made a surprise appearance to keynote my mother’s retirement dinner.

The 1992 election should have been ripe territory for Sanford’s re-election. While George H. W. Bush defeated northern liberal Michael Dukakis by a whopping 58-42%, in 1988, just four years later, Bill Clinton came within 1% of defeating Bush in North Carolina. Democrats regained the Governor’s Mansion for the first time in eight years, as Jim Hunt defeated sitting Lt. Gov. Jim Gardner 52% to 43%. Democrats swept every statewide Council of State race.

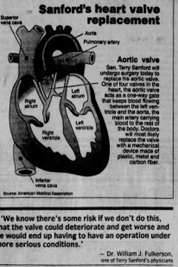

But Sanford’s health became an issue in the Summer of 1992 after he was hospitalized with a heart infection. Sanford was 75 at the time.

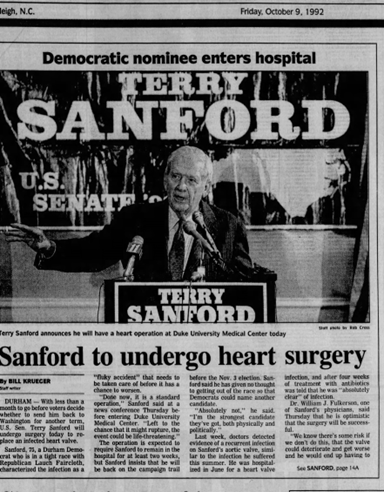

Then just one month before the election, and at a time when everyone still voted on election day the News and Observer announced the “Democrat nominee enters hospital” and “Sanford to undergo heart surgery.” The article and similar ones across the state explained in great detail the procedure to replace an infected heart valve.

The News and Observer reported Sanford had a six-point lead over his Republican opponent, former-Democrat-and-ally Lauch Faircloth, when he entered the hospital for two weeks. No doubt that harsh TV ads attacking Sanford as too liberal for North Carolina, launched by Jesse Helms Congressional Club, were closing the gap. According to the New York Times in September of that year, Sanford was polling so far ahead of Faircloth (+14 points) that Sanford stated its “looks too good to be true.”

The New York Times reported on Oct. 19, that Sanford was returning to the campaign trail and joining US Sen. Al Gore of Tennessee, the Democrats’ vice presidential nominee. The Times reported that in the two weeks that Sanford was hospitalized, the race shifted to Faircloth.

From News & Observer Oct. 9, 1992

In an incredibly brilliant move, led by Faircloth campaign consultant and Congressional Club guru Carter Wrenn, Faircloth, who and been an ally and friend of Sanford before changing parties, launched a “Get well, Terry” ad, encouraging his friend to pull through. It softened Faircloth’s image and reminded voters that Sanford had serious health concerns. Faircloth defeated Sanford 50% to 46% in an otherwise dismal night for North Carolina Republicans. David Parker, who ran the Sanford re-elect campaign, referred to Faircloth’s paid get-well message as “the mortician ad.”

“There is a way to express your concern to a friend of 40 years, you pick up the phone,” Parker told the Greensboro News and Record. “You don’t spend 100,000 to make sure everybody knows your sick.”

Parker said the worst part of the heart surgery was keeping the senator off the campaign trail for several critical weeks, leaving the “campaign without a candidate.” Sanford himself called the hospital stay “a bad political break.”

Reflecting 30 years later, Carter Wrenn told Carolina Journal that he thinks Faircloth would have gotten Sanford anyway, but he “would not have bet in Vegas on it.”

Sanford died of cancer in 1998, eight months before what would have been the end of his second US Senate term, had he won.

1998

Six years later, 70 year-old Faircloth would be defeated by a fresh faced 45-year-old trial lawyer, John Edwards. No doubt the contrast in age and energy was a factor. The News and Observer said one of the striking contrasts was having “one candidate raised during the depression and another who was a baby boomer. “

2008

Obama won North Carolina in 2008, and it was a terrible election night for North Carolina Republicans. Democrat state Sen. Kay Hagan defeated incumbent Republican US Sen. Elizabeth Dole, 52% to 44%, in the last US Senate victory for North Carolina Democrats to date.

The most effective ad against Dole was the “Rocking Chair ad,” which featured two older men arguing about Dole being either 92 or 93 in “effectiveness” in the US Senate. Dole and others believed it was really an attack on her age implying she was in her 90’s in age. She actually was 72.

“I think if someone is going to fib about someone’s age, they really ought to make her look younger,” quipped Dole.

After Dole lost the News and Observer said the swipe at Dole’s age was “hardly veiled.”

Ironically and sadly, it was Hagan, after being defeated in 2014 by NC House Speaker Thom Tillis, that fell tragically ill from a tick bite. In December 2016, Hagan became ill with a type of encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) and was admitted to a hospital.

Hagan’s suffered a difficult passing, dying on Oct. 28, 2019, from complications of Powassan virus, at the age of 66. Today Elizabeth Dole is retired, at 87, further highlighting the unpredictable nature of age and health in politics.