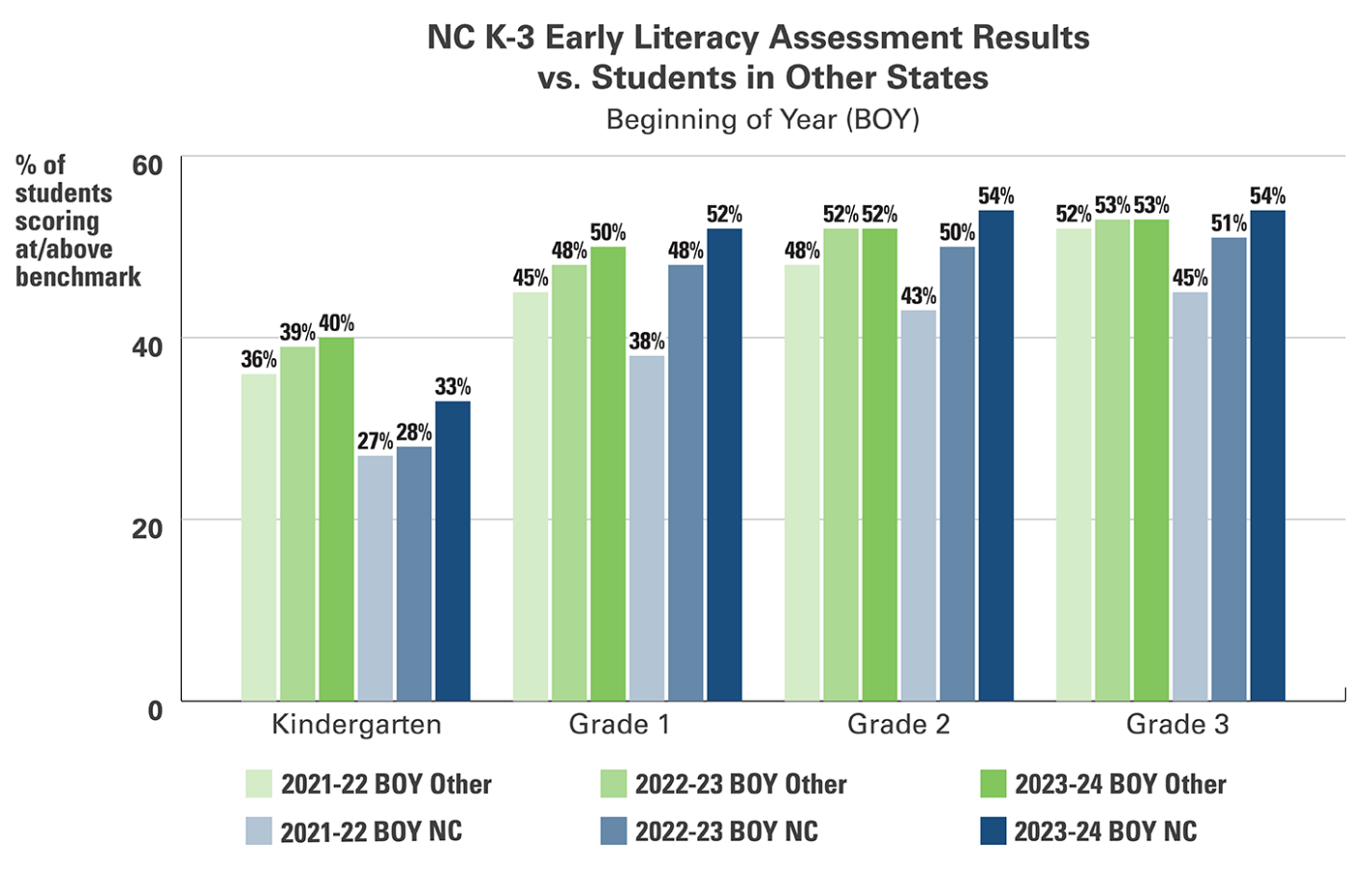

Elementary school students are reading at a better level today than to a year ago, according to new data from the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction.

Since the enactment of a standardized early literacy assessment beginning with the 2021-2022 school year, reading scores in NC for grades 1-3 have outpaced national peers by more than two-to-one, DPI reported.

In 2021, a bipartisan coalition of lawmakers passed the Excellent Public Schools Act, which created a statewide roadmap for switching literacy instruction from a “look and say” method to the phonetic method. The focus was on increasing reading efficiency for K-3 students.

Compared to 2021-22, 9,308 fewer students received a label of “reading retained” this year. Students are considered “reading retained” if they are not proficient in reading by the end of third grade.

“This is great news. And we’re still going in the right direction,” said board member Jill Camnitz at the State Board of Education meeting Nov. 7, where the results were first presented.

In a statement, State Superintendent of Public Instruction Catherine Truitt credited the improvements on implementation of the Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS), a two-year professional development program that helps teachers better instruct in literacy.

“The improvements in our benchmark scores are the result of North Carolina’s incredible teachers and students putting [the science of reading] into practice,” Truitt said. “The fact that we continually see a steady increase in reading proficiency before the LETRS initiative is even fully implemented is astounding. This shows that when we invest in research-based professional development for North Carolina teachers, they produce results.”

The results weren’t all positive, however. In keeping with pandemic-era school issues impacting minority students the most, reading proficiency achievement gaps remain among black, Hispanic, and Native American children compared to whites and Asians. For example, 12% more black students received reading scores indicating they need intensive intervention compared to white students. The numbers are even worse for Hispanic and Native American students, at 18% and 22%, respectively.

“We have much to celebrate, but we must also focus on supporting the children who have not quite caught up,” said Amy Rhyne, director of the Office of Learning at the Department of Public Instruction, in a statement. “With the LETRS learning approaching full implementation and as teachers continue to differentiate their instruction based on individual student needs, we expect these numbers to keep improving.”