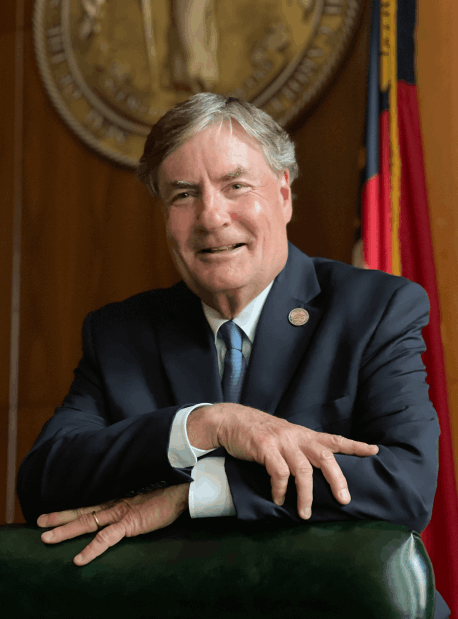

Carolina Journal recently surveyed the four candidates running for a seat on the North Carolina Supreme Court. Below are their answers to core questions on personal judicial philosophy. Read carefully because the stakes are high. November’s two races could shift the balance of power on the state’s high court. For seat 5, incumbent Sam J. Ervin, IV, a Democrat, is challenged by Trey Allen, a Republican. For seat 3 on the court, fellow Court of Appeals judges Richard Dietz, a Republican, and Lucy Inman, a Democrat, are running.

If one of the two seats for associate justice flips Republican, the court goes from 4-3 leaning Democrat, to 4-3 leaning Republican. But in a recent forum all the candidates said that partisan decisions set up a crisis of credibility for the court.

Which current or former U.S. Supreme Court justice best exemplifies your judicial philosophy?

ALLEN: Justice Antonin Scalia. He always insisted that judges must follow the Constitution and laws as they are, not rewrite them to align with the judges’ personal beliefs. In other words, judges must faithfully apply the law to the facts, even when they don’t like the result.

ERVIN: My judicial philosophy is not based upon that of any current or former Justice of the United States Supreme Court. Instead, my judicial philosophy is pretty simple. Judicial officials are supposed to decide the cases that come before them based upon the law, the facts, and nothing else, while giving all litigants a fair hearing and treating everyone as equal under the law. I also believe that partisan politics has no place in deciding the cases that courts are called upon to consider and that judges should take each case that comes before them for resolution with the utmost seriousness given that their decisions have real impact on real people. I use this basic judicial philosophy in deciding each case that comes before me as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court.

DIETZ: The core part of my judicial philosophy is an emphasis on doctrine and judicial restraint, which has been typified by many justices over the years, from Chief Justice John Marshall to Chief Justice William Rehnquist (and several current justices). Because judges can wield significant power in our society, they must commit to upholding the law and rejecting the temptation to decide cases on the basis of their policy preferences.

INMAN: My written opinions for the North Carolina Court of Appeals, which The Carolina Journal has occasionally reported on over the past eight years, best reflect my judicial philosophy, which rests on fundamental principles including the doctrine of stare decisis, honesty, transparency, and the discipline of considering the facts of record and the applicable law as it is written. I apply the plain meaning of text, and when the meaning is unclear, I interpret it using established canons of construction. I strive to decide all cases independent of any outside influence, including my personal views, and reflect that independence by writing opinions that explain my analysis, so that readers can judge for themselves whether they think the decision is fair and impartial. It is impossible for me to identify which United States Supreme Court justice, past or present, best exemplifies my judicial philosophy.

Some judges believe in a “living Constitution.” Others support a concept called “originalism.” Please explain if you endorse either of those concepts. If not, how would you describe your approach to constitutional disputes?

ALLEN: I consider myself an originalist. When interpreting a provision of the Constitution, a judge should be guided by the text as understood at the time of ratification. Judges should follow the Constitution we have, not rewrite the Constitution to mean whatever they want it to mean.

ERVIN: Existing North Carolina law describes how constitutional provisions should be construed. If the language is clear and unambiguous, the provision should be interpreted as written. If that language is susceptible to more than one interpretation, then the judge should look at the way in which that provision has been construed in earlier cases, the context in which the provision appears, the way that other relevant constitutional provisions have been written, the historical context against which that provision was written, the purpose that the provision was intended to serve, and other relevant canons of construction. As a result of the fact that Associate Justices of the Supreme Court are bound by these interpretational principles, I employ them in determining what the constitution means.

DIETZ: In constitutional interpretation, I focus on the key idea that “We the People” ratified our fundamental rights, and the limits on government, and the role of judges is to enforce and protect what the people enshrined in the Constitution. On the spectrum between originalism and living constitutionalism, this approach falls on the originalist side. When I explain my approach to constitutional theory, I often use the example of the U.S. Constitution’s age restriction for the president (35 years old). A judge today might believe that young people are healthier, better educated, and generally more mature than in the 18th century—essentially that “25 is the new 35.” But a living constitutionalist who interprets the U.S. Constitution to permit a 25- year-old to become president would do great harm to the concept of “We the People.” Our constitutional form of government anticipates that this sort of change would come from the people engaging in open discourse and debate, building consensus, and then amending the Constitution as the American framers envisioned.

INMAN: My approach to constitutional disputes is informed by United States Supreme Court decisions interpreting the federal constitution and North Carolina Supreme Court decisions interpreting the state constitution. No judge should employ his or her own individual philosophy as a substitute for the interpretive methods established by precedent unless it is distinguishable or has been overturned. If not bound by precedent, I endorse neither the “living Constitution” approach nor “originalism,” but see those as opposing doctrines on the spectrum of interpretative approaches. I always start with the text of the federal or state constitution. Beyond the text, I explore the context in which it was written. But I do not consider the meaning of constitutional text set in stone as of the date it was ratified. For example, although the Second Amendment of the United States Constitution begins with reference to “a well regulated Militia,” it has long been interpreted to guarantee people who are not members of a militia the right to bear arms. Similarly, although the North Carolina Constitution was amended in 1868 to recognize the right of all people to enjoy the fruits of their labor, and has been considered grounded in the history of an enslaved people obligated to work for the benefit of others but unable to benefit for themselves, the “fruits of their labor” clause has been applied more recently to prohibit government regulation of businesses. Conversely, judges who interpret ambiguous constitutional language only in the context of modern circumstances, with no consideration of its origin, miss the opportunity to consider the historical context and in doing so abandon the institutional principle that the law should develop incrementally, so that our jurisprudence remains stable, consistent, and predictable.

Do you believe that the role of party labels in judicial elections has improved North Carolina’s judicial system? Why or why not?

ALLEN: To the extent that judicial candidates who belong to a particular party are likely to share the same judicial philosophy, party labels can give voters useful information.

ERVIN: I strongly believe that the decision to make North Carolina judicial elections partisan again was an unfortunate one. Judicial officials are required to decide cases based upon the law, the facts, and nothing else while giving everyone a fair opportunity to be heard and treating everyone equally under the law. Although judges are not supposed to try to implement partisan or political agendas through their decisions, the use of partisan elections to select judges suggests to voters that is perfectly appropriate for judges to do exactly that and that voters should evaluate judicial candidates as if they were running for non-judicial office. As a result, I am convinced that our return to partisan judicial elections sends an erroneous signal to North Carolina voters about what courts actually do and is likely to result in declining public confidence in the judicial system.

DIETZ: I don’t think the party labels have any impact on the work judges do on the court. I strongly believe the public supports the idea of nonpartisan judges, but what that means is judges who don’t act like partisan politicians. I believe the key cause of the increasing politicization of the courts is candidates who seek to become judges because they are on a political mission. They’ve been fighting for political causes their whole careers and want to continue doing so as judges. I’ve made the theme of my campaign “leadership, not politics.” I have no political mission. My only mission —from the moment I took the oath as a judge— is to defend our rights, protect the rule of law, and help people resolve their legal disputes fairly.

INMAN: Party labels in judicial elections have harmed North Carolina’s judicial system by giving political parties greater influence in the judicial branch and creating a barrier to judicial candidates who are not affiliated with any political party. Unaffiliated trial judges have been forced to choose a political party to run for reelection. Other trial judges and candidates have switched their party affiliation to match that of the majority of voters in their districts. Unlike nonpartisan elections, which created an incentive for judges and judicial candidates to seek bipartisan support, party labels create expectations that judges will serve their political parties’ agendas and penalize judges who fail to tow the party line. Earlier this year, the chief judge of the North Carolina Court of Appeals was challenged in a primary election by a candidate endorsed by three of the chief judge’s colleagues on the Court of Appeals as well as a justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court who is not on the ballot, all members of the chief judge’s political party. News reports by the legal and business press indicated that the chief judge was accused of “poor leadership” because she had failed to ensure that a hiring decision at the Court of Appeals favored a member of her political party. The press also reported that the chief judge was publicly accused of betraying her political party by associating with judges of another political party. News reports like these, which to my knowledge have not been refuted, undermine public confidence in North Carolina’s judicial system. If citizens do not trust judges to make fair and impartial decisions independent of political parties, and so ignore the authority of the courts, our constitutional democracy is at risk of being replaced by lawlessness and raw political power.