Over recent years, voices across the education establishment have been crying out about a rise in teacher vacancies in classrooms across North Carolina. But things are a bit more complicated.

For example, in Charlotte Observer’s late 2023 article on NC’s alleged teacher shortage, it admits:

School districts opened the school year with 3,584 teaching vacancies, a nearly 20 percent drop from the previous year, according to a survey from the N.C. School Superintendents’ Association. But Jack Hoke, the association’s executive director, said the drop only occurred because schools hired 1,400 more “residency license teachers” [those who haven’t finished official licensure] than the prior year.

So, it turns out the vacancies are being filled at a rapid rate. They are just being filled with people who are not licensed in the traditional way. The article also notes that in the last decade, there has been a 51% drop in enrollment at NC’s “traditional teacher preparation programs,” largely run through the university system. This means traditionally licensed teachers are going to be in shorter supply going forward, so more “residency license teachers” are likely going to be stepping in.

Many don’t want to even consider these new non-traditional teachers as fully teachers though. In another article from last year, Kris Nordstrom of the NC Justice Center, a progressive nonprofit, said:

At the beginning of the last school year, North Carolina faced an unprecedented teacher shortage. On the fortieth day of the 2022-23 school year, 5,095 classrooms were vacant. In other words, nearly one in every 18 classrooms lacked an appropriately licensed teacher.

You’ll notice that in the second sentence it doesn’t say they lack teachers, only “appropriately licensed teachers.” A footnote at the bottom of the article says, “The North Carolina Department of Public Instruction defines a teacher vacancy as ‘an instructional position (or a portion thereof) for which there is not an appropriately licensed teacher who is eligible for permanent employment.'”

That’s important information moving forward if you see and hear comments about the teacher shortage crisis. Many of the classrooms have teachers. They just don’t have the licensing that the education establishment considers “appropriate.”

But does that matter? Bloomberg columnist Matthew Yglesias recently wrote on a Boston University study that found that, after using many unlicensed teachers during the COVID pandemic, unlicensed teachers in Massachusetts had “similar range and levels of effectiveness (as measured by educator evaluation scores and student growth percentiles),” similar rates of retention and intent to remain in the profession, and were actually “more racially/ethnically diverse” and better fit to specific district needs when compared to licensed teachers.

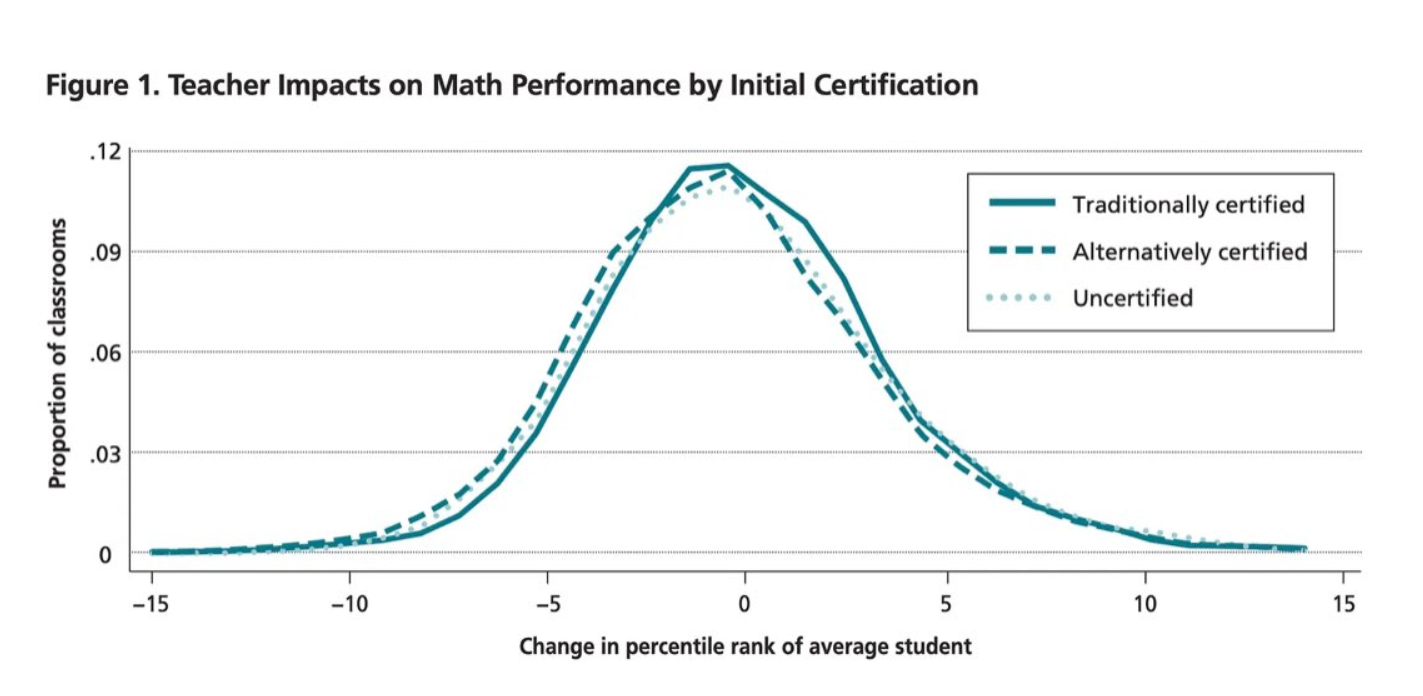

Yglesias said this data from Massachusetts matched a similar pre-pandemic study that found almost no difference in performance between licensed and unlicensed teachers in Los Angeles, as seen in the graph below. What it did find was a large difference in pay, favoring those with licenses.

Some readers responded to Yglesias’ research by saying getting rid of licensure might not impact student performance, but it would reduce teacher salaries. However, requiring people to take on mountains of college debt and spend four of their most productive years in college just to get a boost in pay (a boost that elected officials could give them anyway) doesn’t seem like solid economic reasoning.

So what if North Carolina did away with teacher licensure requirements and let school districts decide who to hire for themselves? As far as I can tell, the main effect would be that school systems would have much less red-tape when hiring and would have more potential candidates — all of this likely leading to fewer vacancies, even if NC DPI decides not to measure it that way.

And an added benefit of this approach is it could reduce the radicalism and activism by public school teachers that is driving so many parents to look elsewhere for how to educate their children. Schools of education are notorious for being among the most radical departments on campuses, so the less time future teachers spend in them, the better.

If you assumed teacher training mostly consisted of lessons on classroom management and learning styles, you may have missed how the UNC Wilmington School of Education faculty and student body reacted to a Republican legislator, state Sen. Michael Lee, being given an awards banquet for his bipartisan work in education.

A mob of future teachers tried to ruin the event in any way they could think of, staging a walkout and causing a disruption. They even followed the senator and his family to their car afterwards, where they surrounded them screaming profanity. The protest was organized in part by a UNCW professor, Caitlin Ryan, whose area of scholarship focuses on injecting “LGBTQ Inclusive Literacy Instruction in the Elementary Classroom” and “Navigating Parental Resistance” to that work.

In addition to making hiring easier and reducing radicalism, eliminating the necessity for schools of education at universities by not requiring teacher licensure could also help free up space in university budgets, allowing them to reallocate resources to other more-productive programs.

As a broader point, occupational licensing for most professions is unnecessary and wasteful, not just in teaching. It more often just serves as a gatekeeping mechanism, which reduces the supply of workers and the products and services they would have created.

Of course, there’s a good argument for licensing in occupations where there’s a high risk of death and injury (to the worker and those they’re serving), like for heart surgeons and airline pilots. But even then, do we think any airlines are going to let someone fly their planes without being absolutely certain they’ve gone through sufficient training? No, and neither will their insurance provider.

Most professions, including teaching, can provide on-the-job training, easing people in, testing their strengths, judging their fitness from experience and ability. Evidence seems to suggest that teaching falls into this category. That doesn’t mean it’s not a difficult or important job. But someone with knowledge of the subject matter and skill in managing children can, it appears, successfully teach. And we shouldn’t stand in their way.