Wild, disruptive protests in support of the Palestinian cause are in progress at campuses across the country. At many of them, there are threats and antisemitic language. But it can be difficult to trace much of what is said back to particular people because of attempts by protesters to remain anonymous by covering their faces.

According to Chapelboro News, UNC Chapel Hill Provost Christopher Clemens asked the group Students for Justice in Palestine (the same group who used paraglider imagery directly after the Oct. 7 attacks) to stop wearing masks. Administrators attempted to bolster their demand by using a 1953 law that was used to prevent the Ku Klux Klan from showing up on campuses with their face covered to intimidate students.

“I am writing respectfully to request that you ask the students not to wear masks (except for allowable medical exceptions or religious head coverings) for their protests,” Clemens said. “This practice, currently encouraged by leadership [of SJP], runs counter to our campus norms and is a violation of UNC policy and State law.”

Protesting is, of course, a vital part of the American free-speech tradition. The right to remain anonymous when exercising this right is also vital. The authors of the Federalist Papers — Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay — are frequently cited in defense of anonymity in speech. These founding fathers wrote anonymously to avoid risks to their careers and physical safety, and it’s argued that Americans still need anonymity in order to effectively argue unpopular positions. The recent “cancel culture” trend is good evidence of this continuing need.

But there have also always been exceptions, when this anonymity was thought to be a hindrance to maintaining law and order. My non-lawyerly understanding is that the exceptions to anonymity in speech align somewhat with the exceptions to freedom of speech in general, in that it is broadly protected unless you are breaking the law or creating a clear and present danger to the public. Unlike most times and places, it is not enough that your words deeply offend someone or, if adopted, that your views would have a generally negative effect on society.

Types of speech that are not protected under the First Amendment, and therefore where your right to anonymity is not guaranteed, include things like: blackmail, defamation, fighting words, national security threats, perjury, plagiarism, solicitations to commit crimes, child pornography, and true threats.

So, for the most part, you are allowed to contribute to the public discourse anonymously, even if your contribution is seen by most as a net negative. This guarantee is only for those on American soil, though.

Because of the national security exception, and because they are not US citizens, we don’t give foreign governments the right to secretly and anonymously propagandize Americans. This issue is relevant right now because Congress just voted to force TikTok’s Chinese parent company to either sell its shares or have its platform banned in the United States.

TikTok CEO Shou Chew did not accept the news lying down and promised to fight it in court.

The bipartisan bill demanding this sale did not arise out of boredom. It’s very clear to observers that China is manipulating their algorithms to boost certain messages favorable to them, and also to their allies in Russia and Iran, while suppressing information that is less favorable to them. There is an anonymous man behind the curtain of TikTok, you could say, and that man is Chinese President Xi Jinping.

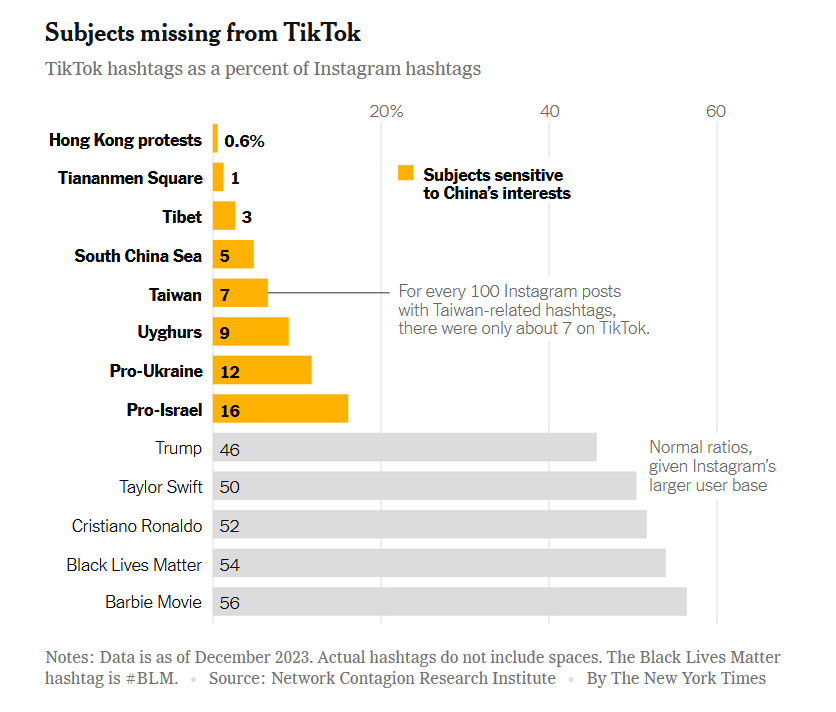

A New York Times breakdown of which topics are allowed and which are suppressed can be seen below. Pro-Western, pro-Ukrainian, pro-Israeli, and pro-Taiwanese topics curiously get little traction, while pro-China/Russia/Iran/Palestine topics appear to be boosted.

Considering about a third of those under 30 get their news, at least in part, from TikTok, that becomes a national security concern. And the current explosion of anti-Israel protests on Western campuses can be at least partially blamed on this fact. Allowing our enemies to propagandize and mobilize our own youth is probably not a smart move, and preventing that from happening is not violating these actors’ right to speech. Neither is there a right for large AI-driven, overseas “bot farms” of fake accounts to interact with Americans without scrutiny.

Aside from the political questions, there is also the cultural impact of anonymity in speech, especially used as a norm rather than an exception. Sure, if you believe you will be in grave danger of losing your job or becoming a social pariah for revealing an honestly held belief, by all means, stay anonymous. But if you just wish to stay anonymous so you can do the online equivalent of hiding behind a rock and insulting anyone who walks by, your speech is a net negative to social capital and the greater cultural dialogue.

There is a clear difference in how people communicate face to face, as opposed to when they’re insulated by layers of “social distance” — to borrow a COVID-era phrase everyone likely wants to forget. If you’re at the grocery store and a little old lady gets to the checkout counter just before you, causing you to have to wait another five minutes, you’ll likely smile politely and maybe even make small talk. But if that same little old lady gets to the intersection in front of the grocery store just before you, causing you to wait just five seconds, you may feel comfortable yelling, honking, or even making a gesture or two.

Add another layer of social distance by making that interaction online, and, even if your name and image are displayed, you may go a step further. Ironically, sometimes I meet someone in person who is among the biggest firebrands online, and they are gentle and soft-spoken. Without the online anonymity, they’d probably have much more civil and productive conversations.

Go one step further still in social distancing, by taking your name and headshot off your profile, and you get the rise of sociopathic “trolling” behavior done by so many anonymous profiles, much of which would brush up against free-speech exceptions (like threats, harassment, and fighting words) if done in person.

So while there is an important role for maintaining a right to anonymous speech in our democracy, there are real dangers inherent to it. We should be aware of what a rare privilege it is and not treat it like a plaything. Citizens who abuse this anonymity to commit crimes are not guaranteed continued anonymity; neither are foreign actors cynically hiding behind our freedoms for propaganda purposes. And, if you are not in grave danger, consider standing bravely behind your views so anonymity doesn’t become a temptation to degrade the public discourse for your own amusement.