This week, people around the world were horrified by images of the worst brutality human beings can inflict on other human beings, perpetrated by Palestinian Hamas terrorists on Israeli civilians.

Some of these civilians were Holocaust survivors. Some of them were children, with 40 babies reportedly beheaded in one village alone. Some were residents of farming villages, where entire families were wiped out. Many, around 300, were young concert-goers attending a music festival advocating the end to hate and war.

In the most cynical and cowardly act possible, the terrorists mowed down these hopeful kids dancing for peace. The pure evil of it all has had my mind and heart wrestling with one another ever since. What kind of universe do we live in where beheading a baby is permitted? What inspires someone to carry out this level of atrocity? If people reaching out for love and peace are treated this way, is there anything that can put an end to old vendettas? Is our only answer to kill them first, which almost always creates civilian deaths?

My reflections ultimately led me to consider the degree resentment poisons individuals and cultures and how it excuses many of the worst atrocities.

Communists were able to convince untold millions that their economic difficulties were the fault of the wealthy. After stripping these elite of their possessions and sending them to work and die in the gulags, attention had to turn towards the kulaks, peasants who had been able to become slightly less poor than their neighbors after serfdom was abolished. Soon, everyone with any talent or education was designated a kulak, a non-person on whom all one’s resentment could be taken out. Their meager success must have been earned at others’ benefit, in the Marxist thinking, a mindset echoed in our “equity” movement.

The Nazis in Germany also powered their death camps with resentment. After their nation was on the losing side of WWI, they experienced humiliation, hyperinflation, and economic ruin. Hitler was able to effectively create a scapegoat out of the Jewish population. Like with the kulaks to the east, the relative success of their Jewish neighbors gave Germans an excuse to avoid taking responsibility and to resent instead.

The same force is clearly at work in Palestine and has led to a culture of deep resentment towards Israelis and Jews in general. In Palestine they have weekly children’s cartoons and puppet shows where the lovable anthropomorphized animals sing songs and teach kids how to kill Jews. In their schools, the children are also brainwashed to violence, as can be seen below.

One might say that they are only responding to their circumstances. They were forced off their land and justice demands Palestine be returned to them. But it’s clear that the more they’ve fought, the less land and freedom they’ve ended up with. Israel was perfectly fine with Arabs being part of the State of Israel (and 20% of Israel today is made up of Arabs). But when most local Palestinian Arabs, under the leadership of Grand Mufti Amin al-Husseini, allied with Hitler and devoted themselves to his “Final Solution,” their resentment led to war.

Each time Arabs declared war on Israel, Israel came away with more land, most of which (like the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt and Gaza) they gave back. After this latest attack, it’s unclear whether there’s a future for the idea of a Palestinian state at all.

A quote I’ve seen attributed to everyone from Princess Leia to Friedrich Nietzsche says, “Resentment is like drinking poison and expecting your enemy to die.” The absolute destruction that has occurred in communist nations, Nazi Germany, and Palestine is good evidence that is the case.

Interestingly, a sort of Global Axis of Resentment has emerged. I’ve seen everyone from white supremacists to far-left socialists to Black Lives Matter activists come out on the side of Hamas’ attack, only united by their resentment.

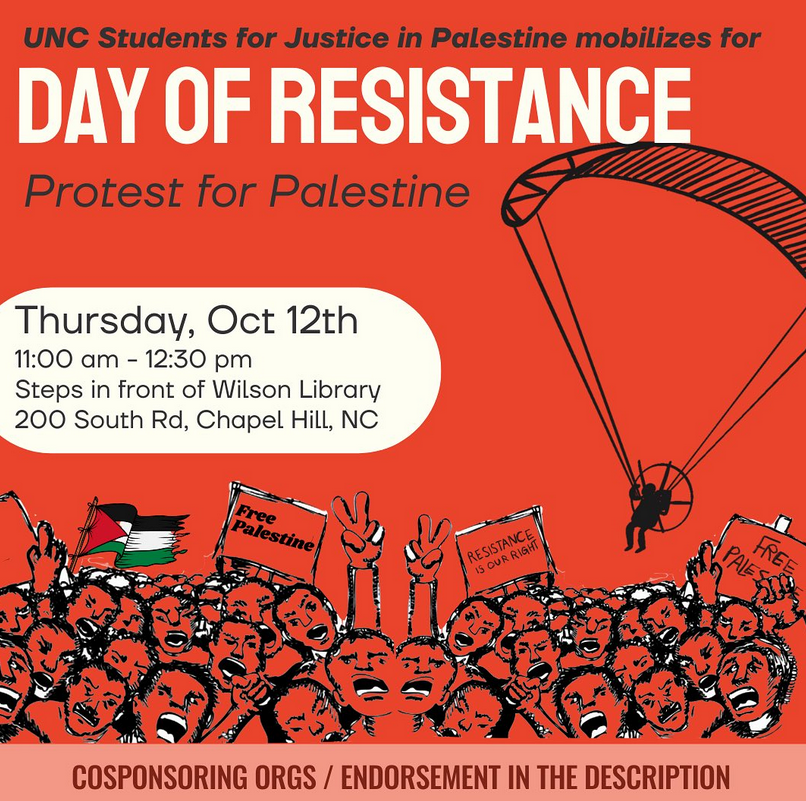

An example of this locally is UNC’s Students for Justice in Palestine, who put an image of the paraglider on their flyer for a pro-Palestine “Day of Resistance” event. The paraglider, you’ll remember, is the mode of transportation that Hamas took into the peace concert, where they raped and murdered hundreds of civilians.

There was a lot of negative publicity on the students organizing the event, which included the UNC Young Democratic Socialists and some “Defund the Police” groups, but they went through with it anyway. The event, apparently, devolved into violence at times, and a Jewish professor was pushed down the stairs by the pro-Hamas group. Both of the state’s US senators even spoke out on it.

A resolution at the North Carolina General Assembly to denounce Hamas’ attack and declare solidarity with Israel also led some to surprise pushback from the left, as 12 House Democrats and four Senate Democrats walked out of the chambers rather than vote. In statements since, they have largely said their reasoning was that the statement did not include enough about protecting Palestinian civilians. Another said she walked out because she was angry about other votes taken directly before.

I’m not going to pretend everyone on the left in this country is fueled by resentment or that nobody on the right is. I’ve seen plenty of it from all sides. But there seems to be an ever-present danger of legitimate movements for justice motivated by real historical wrongs being slowly poisoned by resentment.

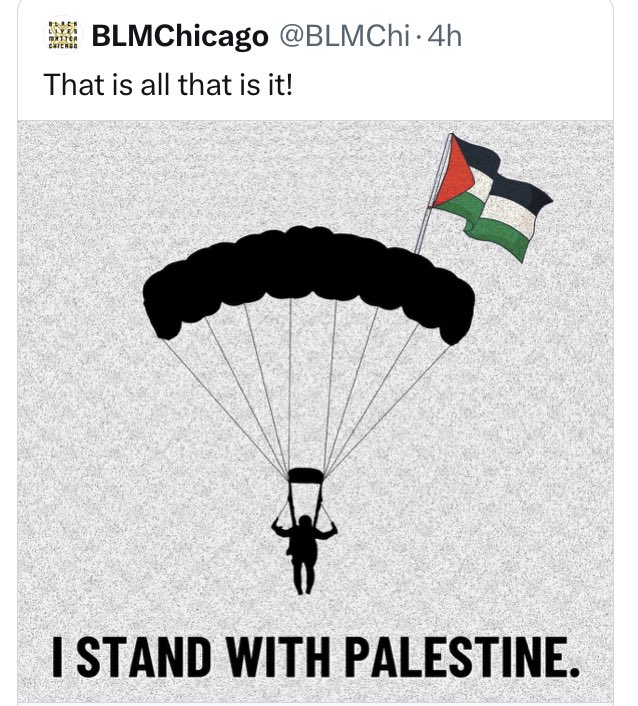

For example, Black Lives Matter, a group in part responding to the clear mistreatment of black Americans over the centuries, is entirely fueled by resentment. They make that clear when they advocate for rioting and Marxism, and they make it clear when they use the same disgusting paraglider symbolism that the UNC group did.

There is also resentment in the dynamics between men and women in our culture. It is assumed that a win for men must be a loss for women, or vice versa, like we are two competing interest groups rather than two necessary sides of the coin for the human species.

The deep resentment from all sides may have roots in a real injustice, but vengeance will not resolve it. Resentment, like any of our passions, has to be controlled or it will run wild. In a moral culture, the people control their passions themselves, but if we are unwilling or unable to control them ourselves, we are calling for an outside power to come in and do it for us.

As Edmund Burke said, “Men are qualified for civil liberty in exact proportion to their disposition to put moral chains upon their own appetites… Society cannot exist, unless a controlling power upon will and appetite be placed somewhere; and the less of it there is within, the more there must be without. It is ordained in the eternal constitution of things, that men of intemperate minds cannot be free. Their passions forge their fetters.”

And the only way to control the particular passion of resentment is to forgive, or as one local Jewish man put it, “Love your enemies, bless those who curse you, do good to those who hate you.”