While most of North Carolina’s political observers have been focused on the long-awaited completion of the state budget, there have also been other bills progressing through the legislature — like SB 189, Fentanyl Drug Offenses and Other Related Changes, which increases fines and penalties for distributing the drug and sets up a task force to come up with new law enforcement strategies.

The bill aims to crack down on fentanyl and other powerful synthetic opioids, a positive step in an environment where over 100,000 people per year are dying of drug overdoses, including over 4,000 North Carolinians. The explosion of these deaths, which used to total around 5,000 people annually nationwide before the new millennium, has made it now the leading cause of death for adults 18-45, higher than other major causes like car accidents or heart disease. Over 70% of overdose deaths are due to fentanyl, an opioid so powerful many immediately overdose and die when they try it for the first time.

State Sens. Tom McInnis, Danny Britt, and Michael Lazzara introduced the bill, which passed the Senate unanimously in March. This week, SB 189 also passed the House, albeit with 20 Democrats voting against. Now the bill heads to the governor for his signature or veto, and at least some on the left think he should choose the latter.

Before the House vote was taken, a coalition of “harm reduction” advocates, including the NC Council of Churches, sent out a press release denouncing the bill.

“Amid State’s Worsening Overdose Crisis, Harm Reduction Advocates Argue SB189 Will Fuel Deaths and Systemic Racism,” the statement begins.

To back the claim that arresting fentanyl dealers will increase overdose deaths, the harm reducers say, “Prosecuting dealers disrupts the drug supply, leading to more preventable overdose deaths.”

This, clearly, ignores the fact that fentanyl dealing is already highly illegal, so supplies are already disrupted when they are arrested. Increasing the fines and penalties on dealers isn’t going to make much difference on that front. But it might act as a deterrent and reduce supply.

The study they cite, from NC State, looked at Haywood County after the original death-by-distribution law was implemented. Either those sending the press release didn’t read it, or they hoped the reader wouldn’t. But the study found the impact of the law was actually a lowering of overdose risk (because dealers lowered potency to avoid the serious charge) in the short term. The study did say there was a possibility of a greater risk in the longer term, but they were unsure, so their biggest takeaway was, “Our study demonstrates most conclusively that further research on the individual and community-level impacts of DIH laws is urgently needed.”

Harm-reduction proponents are fond of calling all their claims “evidence based,” but I’ve found their evidence to be paper thin, like this claim that “prosecuting dealers lead[s] to more deaths” with the study saying mostly the opposite as proof.

After presenting their weak evidence, they go on to demand action based on it: “It is time for lawmakers to recognize the failings of the Drug War, and come to the realization that we cannot punish our way out of the overdose crisis.”

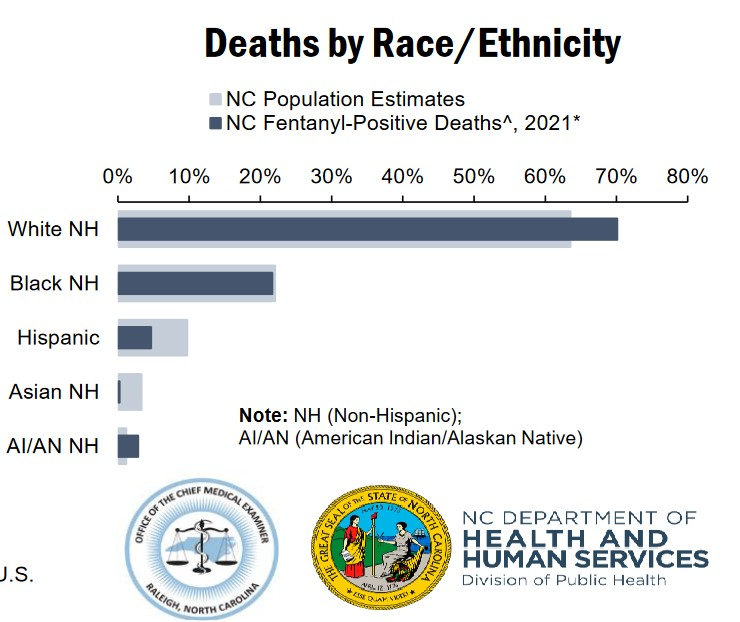

They also state that cracking down on fentanyl dealers would “widen racial disparities among the incarcerated” and fuel “systemic racism.” But they don’t even try to give a defense of those statements. Looking for data on fentanyl overdoses, I found Hispanics and Asians are underrepresented among fentanyl overdose deaths, black residents are about proportional, and whites and American Indians are overrepresented. So, unless they have data to show that the racial makeup of fentanyl dealers is drastically different than for fentanyl users, this is not an area to fight “white privilege.”

‘Harm reduction’: more harm than good?

For those just hearing about “harm reduction” as a concept and a movement, you might be tempted to withhold judgment after this one ridiculous press statement. But this is really a fairly good display of the level of moral confusion, tortured reasoning, and fuzzy studies one finds from them.

If their area of supposed expertise was something less important, it might not be a big deal. But their terrible ideas are causing real harm — ironically.

Every “enabling” behavior that drug counselors always told family members to avoid because it observably makes the problem worse — removing accountability and stigma; handing out money, drugs, and paraphernalia; providing housing with no strings attached — has now been declared part of the “evidence-based” best practices of harm reduction. These strategies are also now backed by government grants.

They create “needle exchanges” and “safe-injection sites” so users can continue their deadly habit “safely.” The “safe-injection sites” spread from particular buildings out to the street and into the surrounding neighborhood. And the needle exchanges quickly turn to needle handouts, since the used needles are largely discarded on the street rather than returned, leaving kids to dodge them on the way to school.

Harm reducers create “housing-first” programs across the country, which literally just give housing to homeless drug addicts, under the theory that the reason they are using highly addictive and deadly drugs is just to cope with poverty. San Francisco, which has dutifully put in place every harm-reduction strategy, has implemented this housing first idea. But the apartment buildings tend to turn into dangerous drug dens, not places of healing and recovery. The city also just hit an all-time high in overdose deaths. So much for “evidence based.”

Harm-reduction advocates frequently denigrate abstinence-based and faith-based programs, despite clear evidence for success in long-term in-patient treatment centers, like TROSA in Durham’s over 90% success rate in their two-year in-patient program. But instead, harm reducers suggest “MAT,” medication-assisted treatment, basically giving addicts a steady dose of opioids without any plan for them to stop.

When I spoke with an NC harm reduction leader last year, she told me giving up drugs is not the right path for everyone, so the important part was preventing the downsides, like overdose and disease — as if life as a grovelling slave to a chemical isn’t a “harm” worthy of eliminating.

To witness the full impact of these programs, look no further than the cities where “harm reduction” has had complete power to implement their backwards ideology — Seattle, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Portland, Los Angeles. In each of these cities, large sections are simply abandoned to the harm-reduction plan and the lawless hellscape it creates. Mimicking their strategies would be madness.

North Carolina gets $1.5 billion in settlement money from the lawsuits over opioid painkillers. Sadly, it looks like much of that money is going to be wasted on these harm-reduction efforts, rather than on involuntarily commitment of addicts to long-term, abstinence-based, in-patient rehab, which is how I’d spend nearly every penny.

For example, here is one of the approved strategies that counties can choose in the NC Memorandum of Agreement: “Syringe service programs and other evidence-informed programs to reduce harms associated with intravenous drug use, including supplies, staffing, space, peer support services, referrals to treatment, fentanyl checking, connections to care, and the full range of harm reduction and treatment services provided by these programs.”

The entire NC MOA document is loaded with the terms “harm reduction,” “MAT,” “evidence based,” and all the other buzz words connected to this movement.

I suppose if you see their drug use as a given, or as a free choice we shouldn’t interrupt (even though addicts, by definition, aren’t making free choices), then there’s some logic to these strategies. But North Carolinians should be able to see through that and see that these strategies are harm amplifiers, not harm reducers. We can do better.