In 2016, popular physicist Neil deGrasse Tyson set the internet on fire with a single tweet:

He was raked over the coals for days, weeks, for suggesting that a country could be ruled by scientists and their “factual” proclamations. Tyson even expounded further on the idea in a video, where he said that because people have so many different worldviews, agreed-upon facts were the only practical basis on which to govern.

The Federalist tore his idea to shreds, in an article called, “Neil DeGrasse Tyson’s ‘Rationalia’ Would Be A Terrible Country,” and people everywhere mocked the idea of “Rationalia” as childishly simplistic and naive.

The Empire Strikes Back

But the land of Rationalia was not so easily defeated, as we will see in this week’s outrageous story of the week. It will be valuable to revisit it just to show again why it is so dangerous.

The comment that brought the idea back to the fore was from former UNC Chapel Hill Chancellor Holden Thorp, who is now the editor-in-chief of Science, an alleged leading journal of cutting-edge research.

Thorp, responding to an article by Nature Magazine, tweeted that scientists should be deeply involved in politics.

His graph showed that Republicans are more wary of scientists taking active policy roles, while Democrats are more comfortable with the idea. He goes on to say that scientists “must fight back” at the infantilizing suggestion that they “stick to the science.” The Nature article he referenced suggested scientists should take a much more aggressive approach politically, even by endorsing candidates.

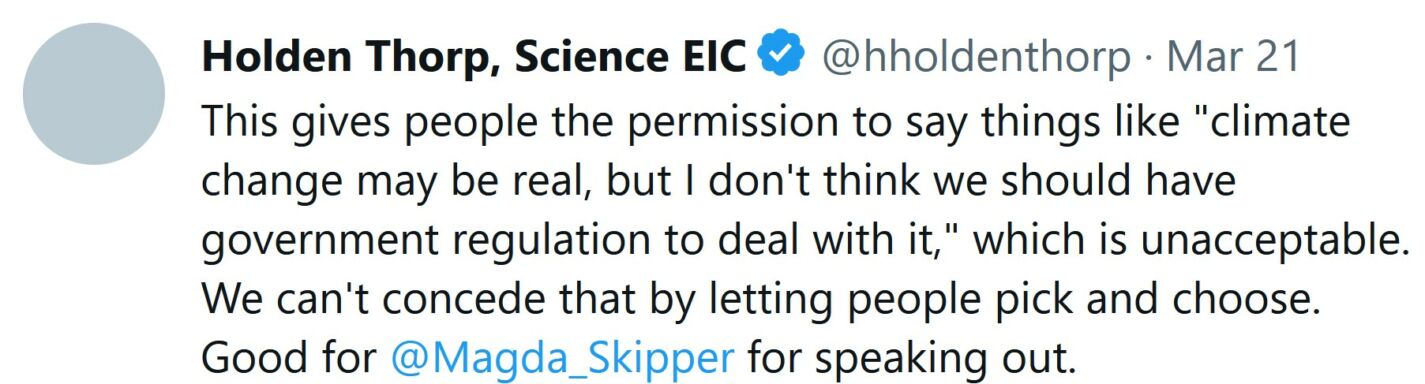

But then, he took things a step further and suggested, in a now deleted tweet, that not letting scientists guide policy “gives people permission” to do things like oppose big government solutions to climate change, which he says is “unacceptable.”

In Rationalia, not only will the scientists tell you exactly what is going on, but they’ll tell you how to fix it. And apparently, any solutions that do not involve government are off the table.

Why that doesn’t work

Off the top of my head, I can think of three major flaws with this kind of thinking. First, “experts” have been so catastrophically wrong so many times, that putting this much trust in them is pretty difficult. It also eliminates the idea of a government of, by, and for the people, but that’s another matter.

There is real power in the scientific method to understand the material world and how it operates, but some humility is called for by scientists on what they can and cannot tell us. During COVID, they got virtually every possible thing wrong. Their “trust the science” policy recommendations also were largely wrong. On something like climate change, I suspect many of their predictions may fall a little short too.

Next, there is the is/ought distinction, a term attributed to philosopher David Hume. Basically, just because you know facts about a certain thing, even if you knew ALL the facts, that would not mean you knew how to respond to them. The answer to that is a separate question, and those of different ethical views will have completely different perspectives.

Let’s say we know that a unique human life with it’s own genetic makeup is present from the time of conception, does that prove that we should preserve it? I would argue, outside of some extreme exceptions, yes. Many others, who have different ethical frameworks, would argue otherwise.

The same could be said for something like climate change. If we knew the earth was going to warm by X amount if we kept using fossil fuels and that this warming would have certain effects, does that tell us exactly what to do? Is cutting off developing nations from the fuel they need to survive the right thing? I’d argue not, but those with different ethical frameworks would argue otherwise. Knowing what is, even if it was completely certain, wouldn’t tell us what we ought to then do.

Lastly, Rationalia doesn’t work because human beings have to implement it. Human beings use any power at their disposal, even science, for selfish and corrupts purposes. This has been seen throughout history.

One recent example is that a major university in North Carolina created phony classes and fraudulent grades so their star athletes could continue winning games without having to worry about inconvenient tests and term papers.

The chancellor even resigned over the matter. I think he’s the editor of a major science journal now. Regardless, it shows that, while experts at universities and science labs have valuable input, their data, their conclusions on how to respond to that data, and their characters are quite often flawed, just like the rest of us. Giving them the reins of power on the assumption they know best would not be wise.