Psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s new book, “The Anxious Generation,” lays out the latest research on what constant screen time is doing to America’s youth. And the trends are very troubling. Haidt shows how mental health problems, sleep deprivation, social isolation, suicide attempts, and attention fragmentation have all spiked among youth and suggests a direct link to “screen time,” especially smart phones and social media.

He contrasts this “phone-based childhood,” and all its difficulties, with a “play-based childhood,” where previous generations learned to develop appropriate habits and mindsets, like how to socialize and how to handle loss with resilience. To return to this healthier, more-natural dynamic, Haidt recommends four rules for America’s youth:

- No smart phones until later teen years (use flip phones instead)

- No social media until later teen years

- More free-play time, where children can learn to interact without constant supervision and intervention from adults

- Ban smart-phone use in class

The other rules also seem wise and necessary to address this issue from a parenting perspective, but the rule regarding smart devices in schools seems to be the one with the biggest relevance to policy. So I’ll focus there.

Schools and districts in our state are signaling their agreement with Haidt’s main concerns about smart phone use in schools, as they have independently created a patchwork of policies to address it in recent years.

In the North Carolina School Boards Association’s recommended policies, they encourage schools to tightly restrict smart phone use in class. Christine Scheef, the legal counsel and policy director of the NCSBA, told me that while this is their model policy, local districts have wide latitude to apply, customize, or ignore these recommendations.

She said the policy in Onslow County, which a Jacksonville Daily News article says was influenced by the NCSBA language, hews fairly closely to their wording. The article says this policy creates a dynamic where smart devices can be on campus “so long as the devices are not activated, used, displayed or visible during the instructional day or as otherwise directed by school rules or school personnel.”

Similar policies to the one adopted by Onslow County have also been adopted by public school districts in nearby coastal counties like Craven, Wayne, Pitt, Pender, and New Hanover.

Craven County’s policy this school year is to confiscate phones being used during lessons and to give a three-day suspension to those who continue to violate the rule.

Unsurprisingly, when ABC-12 interviewed parents and students about it, not everybody was happy. Parents worried about not being able to get in touch with their children at a moment’s notice, and students felt that it wasn’t necessary or fair. The teachers, on the other hand, said that before the policy, many students would just watch movies on their devices during class, ignoring lessons and not interacting with their fellow students.

At the beginning of this school year, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, the second largest district in the state, also announced that there would be no cell phone use during class time. Assistant Superintendent David Legrand told WFAE that when students returned to in-person class after the COVID lockdowns, they were using their devices much more than before, including while teachers were giving lessons. He told WFAE that this year they would still be allowed to bring them to school, but they’d have to keep them turned off and out of sight.

Surveying other districts and individual schools across the state, many others, both urban and rural, have moved to restrict smart phone usage in class.

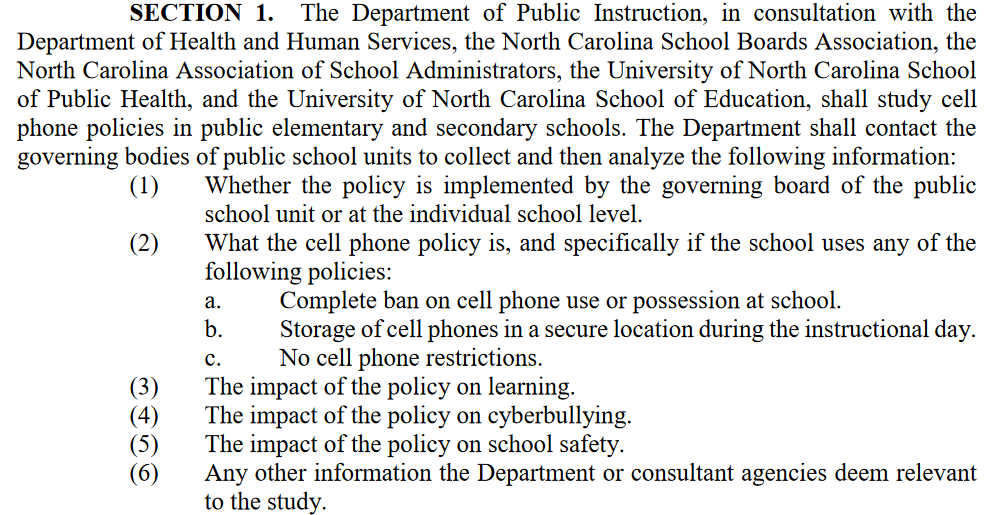

State officials have taken note of the issue. State Sen. Jim Burgin, R-Lee, is a primary sponsor of SB 485, Study Cell Phone Use in School. Burgin, and his bipartisan sponsors, want the state’s Department of Public Instruction to investigate what cell phone policies are in place across the state and what results various strategies see. The bill was sent to the Rules Committee and not taken up during the 2023 long session, but it could be refiled or otherwise revived in the upcoming short session.

Burgin’s office told me, “Sen. Burgin is passionate about this bill due mostly to the mental health of our young people but also feels that it would improve performance in schools as well.”

A study like this was done in England at high schools in their largest cities, and when schools implemented bans on mobile phones, they saw “significant improvement in scores on high-stakes tests.” Low-performing students especially benefited, with double the increase in scores as other students. But higher-achieving students also saw a big boost, getting the equivalent of an extra hour of learning per week and evidence of improved focus.

With data like this, England decided to ban smart phones in schools nationwide, a move that was implemented at the beginning of this school year. France and the Netherlands have also passed similar bans.

North Carolina has a lot more local control on education — and, in addition, has many students learning in private schools and homeschools — so a statewide mandate like what England did is unlikely. But if a “best practices” emerges that sees smart phone use as unwelcome in class, it appears that would be a positive outcome for student mental health, test scores, and behavior.

Parents should also take into consideration Haidt’s recommendations on smart phone use in general. It could be that giving your child a smart phone with unlimited access to social media, video games, and other addictive apps is doing them much more harm than good. Even if parents do not heed these warnings, many students across the state are now at least getting a break from their screen-based world during class.