There are a lot of efforts from politicians, from both sides of the aisle, right now to protect children from online dangers.

US Sen. Ted Budd sponsored a bill to block TikTok and other addictive social media platforms from being accessed at schools that receive federal funding.

North Carolina legislators passed the Pornography Age Verification Enforcement Act (PAVE), which was also passed in many other states, this session to require online pornography sites to verify the age of users before granting access.

And then, this week, NC Attorney General Josh Stein announced that he and 32 other state attorneys general had sued Meta, the parents company of Facebook and Instagram, for using techniques they knew were addictive and for illegally gathering data from children under age 13.

“Meta knew it was harming our kids,” Stein said. “And Meta lied to parents and the public about the risk its social media platforms posed against our young people.”

Many of these moves by legislators around the country are likely good. If we can keep young kids away from social media, pornography, video games, and other addictive, time-wasting, vice-creating online activities through reasonable regulations that don’t violate free-speech or free-market principles, I’m all for it. We don’t allow children to do other provably harmful activities, like smoking or drinking, so in principle, it makes sense.

But the much bigger issue is that parents are not monitoring their children’s online habits. Young boys have more of a tendency to become addicted to video games and pornography, and young girls have more of a tendency to become addicted to social media. And parents, often addicted to screens themselves, are clueless or apathetic.

If the age-verification law prevents a young boy from accessing a porn site, great. But in all likelihood, they will find another way to access similar content if no adults are keeping an eye on them. The average age for first seeing pornography is 12, according to a study by Common Sense Media, and 15% said they began viewing it at 10 or younger.

The impact of this on developing minds is still becoming clear, but one study into it had to be canceled because they couldn’t find a control group of young men who had not viewed pornography. Young boys are even more obsessed with video games.

A Mott Children’s Hospital national poll of parents who had at least one teenager found that 9 of 10 parents said their children spent too much time playing video games to a degree that impacted their social and family lives. The study found that boys were twice as likely to spend time playing video games than girls, at over 3 hours a day average. After time at school, some homework, and, hopefully, a family dinner, that’s probably the remainder of their day. But it also found that only 44% of the parents claimed to be taking any, even minimal, actions to limit time or adult content. The most common action was simply looking at the content rating.

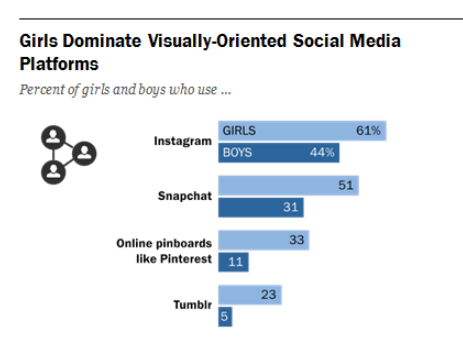

Teen girls don’t typically get pulled into video games or pornography, but they spend about the same amount of time as boys do online, instead using social media sites like Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok. Common Sense Media reports that 45% of teen girls who use TikTok feel addicted and use it more than they want to.

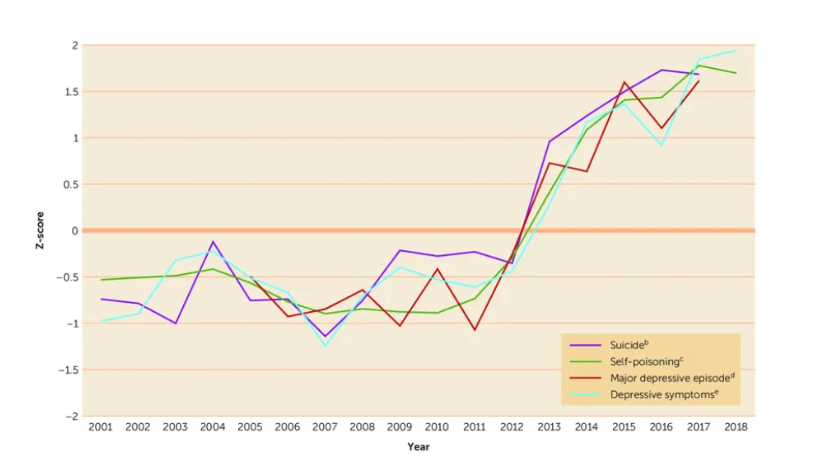

Jonathan Haidt, a social psychologist at the NYU Stern School of Business, has done extensive research pointing to social media being responsible for a sharp rise in mental illness among girls. He, like Stein, specifically points the finger at Instagram.

Jordan Peterson, another psychologist and social commentator, points out the large jump in mental health problems in teens that arose around the time of social media’s rise.

It’s clear to many — left, right, and center — that there’s a problem. And passing laws regulating social-media companies, pornography websites, and video-game companies is a good step. But it’s not a silver bullet, and it’s definitely not a replacement for personal responsibility and good parenting.

Without parents taking the wheel, the laws are unlikely to make a dent in the problem, in the same way that without good parents, throwing more money at government schools with low scores and behavioral problems is unlikely to make much difference. There are enough old video games and porn scenes to fill many lifetimes for any boy. There will also be new social media sites and other dopamine-rush-inducing websites for girls to spend their time on. Every new law will likely just send these kids on a short journey to find a workaround or a replacement website or app.

The real challenge will be to create a culture where parents are offering alternative leisure activities that are healthy (mentally, physically, and socially). If the children aren’t immediately enthused, it may take exercising some authority. For example, parents don’t have to give their children access to devices — like smart phones, video-game consoles, and personal computers.

The reason parents aren’t already monitoring and setting boundaries on the dangerous online habits of their kids is likely that parents themselves are addicted to their screens. They are also chasing dopamine hits from many of the same sources as their children are, as well as from news and podcasts and all the other endless forms of engaging content now available. For many parents, if their teen is playing video games or scrolling on their phones, it gives them an opportunity to “take a break” and do the same.

So rather than expect a few new regulations from the government to solve the teen mental health crisis, parents will need to live by example, put down our own phones, and invite our children to join us in finding something better to do.