- Outrageous story of the week

That may sound like the irritating old Mary Poppins tune (which I was forced to endure as a kid when it was my sister’s turn to pick the movie), but it’s actually Democrat Gov. Roy Cooper’s explanation for why he was unable to stop an abortion-limiting bill despite his veto.

In an interview with CBS’s “Face the Nation,” Cooper called the General Assembly districts “super-gerrymandered.” He also called earlier maps by the Republican-led legislature “technologically diabolical gerrymandering” on CNN’s “New Day” and used the same phrase this week on MSNBC. Both those comments can be seen in clips made available by Carolina Journal’s Alex Baltzegar.

With Cooper’s veto pen no longer so mighty, he decided to go on national television and blame it on gerrymandering. As he frames it, it may sound like something quite atrocious, but have Democrats really been shut out of power by diabolical Republicans in some unprecedented way?

A very brief history of gerrymandering in North Carolina could be instructive for those who have only really looked at the maps drawn since 2011, when Republicans took over at the General Assembly.

From the end of post-Civil War Reconstruction until 2011, Democrats had a virtual lock on power in North Carolina and largely drew whatever maps they wanted to maintain their power. But the state shifted further and further away from them, until, in the red wave of 2010, even their maps couldn’t save them.

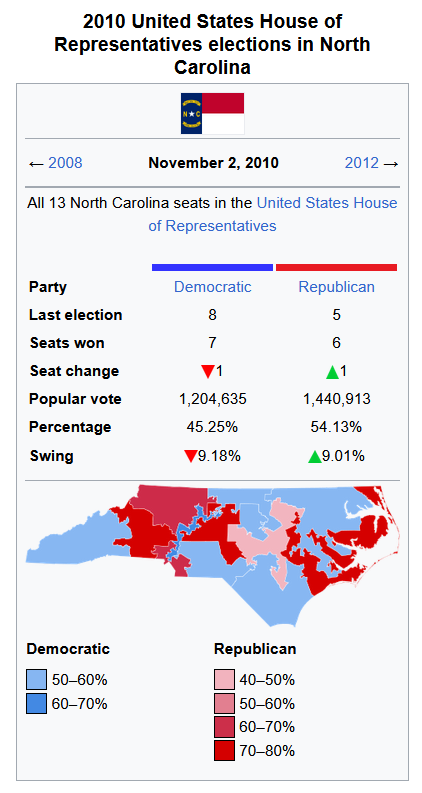

Look at the final Democrat-drawn congressional map, for example. Democrats earned seven seats in Congress with their 45% of the vote, while Republicans earned six seats for their 54%. And look at those district lines. Do they look like they were drawn with an eye to fairness or to maximize partisan advantage?

Their legislative map drawing was equally egregious until courts reasserted the “whole-county provision” from North Carolina’s constitution. The provision says that counties cannot be broken up if it can be helped while drawing legislative maps. This 2002 decision in Stephenson v. Bartlett aimed to rein in Democrat gerrymandering and was among the biggest reasons the party lost its generations-long grip on power.

The current maps

The maps that Cooper is calling super-technologically-diabolical gerrymandering, though, were not as controversial as those Democrat maps (or even other post-2010 Republican maps). The state House maps were passed 115-5, meaning almost all Democrat House members approved them. And the Democrat-majority state Supreme Court also signed off on them.

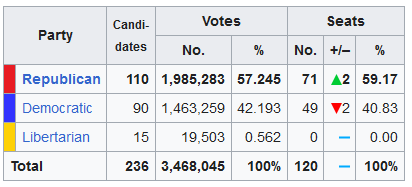

The state Senate maps, on the other hand, did see some controversy and had to be approved by state courts and their “special masters.” But under the version approved by the special masters, Republicans won 59% of the vote. It takes 60% of the seats to get a supermajority, so the results fairly closely mirrored the vote.

Gerrymandering isn’t the Democrats’ real problem

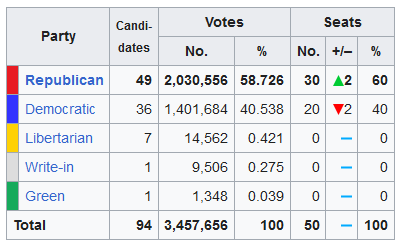

Admittedly, that 59% was partially due to the fact that Democrats are so noncompetitive in certain parts of the state that they didn’t even bother to run a candidate. But even in the House map, which everyone agreed was fair and not gerrymandered, Republicans received 57% of the vote, which got them 59% of the seats. In the end, the difference between the “super-technologically-diabolical gerrymandering” and a totally normal map was between having a 60% supermajority versus being one vote shy of a supermajority with 59% of the seats (until Rep. Tricia Cotham decided to switch parties).

Either way, Republicans were going to be pretty close to a supermajority. And the reason has less to do with gerrymandering than it does with how the Democrat voters are spread out in the state — or more precisely, how they are not spread out.

With the Stephenson decision requiring map-drawers to keep counties whole wherever possible, it is no small thing that the Democrats are all packed into a few urban and suburban counties, leaving maybe 75 of the 100 counties beyond their reach. They are racking up wins around the Triangle, Triad, Charlotte, and Asheville, but then losing big most everywhere else.

Republicans would actually have to gerrymander against themselves to fix this problem for the Democrats during the map-drawing process. Cooper and his party shouldn’t count on them to do that.

But maybe his going on Sunday shows to complain about the maps is less about confronting a real problem and more about laying a plausible defense of an apparent failure so he can get ahead of the narrative for when he seeks out his next political office.

Correction: Republicans won six seats, not five, in North Carolina’s 2010 congressional elections.