This week, Democrats in the N.C. Senate filed a bill aimed at curbing defections from their party — clearly in response to the high-profile departure of Democrat-turned-Republican state Rep. Tricia Cotham of Mecklenburg County.

The bill’s primary sponsors are Democrat state Sens. Natasha Marcus of Mecklenburg County, Michael Garrett of Guilford, and Sydney Batch of Wake County. S.B. 748, the Voter Fraud Prevention Act, in part would require a special election if a legislator switched parties with more than six months to go in their term. It would also require the return of campaign contributions by any donors that disapprove of the switch.

Marcus, Garrett, and Batch, along with the official N.C. Senate Democrats account, took to social media to make their case. Batch said the bill protects N.C. voters from being “swindled by politicians.”

Her Wake County colleague, Republican state Rep. Erin Pare, pushed back. She said that Batch had portrayed herself as a moderate but is legislating as a progressive, suggesting that switching party identification may not be the only way to surprise one’s supporters.

Marcus, for her part, said the bill was necessary because people can’t “completely switch teams, put on the other jersey and starting scoring goals for the opposite team.”

Of course, there’s some truth to the idea of politics being a horserace, a battle, a bloodsport between two opposing forces. This is true in North Carolina and in the nation at large. But are legislators elected to one of two teams to which they owe total loyalty, by custom if not, currently, by law?

Hardly. Things are much more complicated than that. American democracy is a “first-past-the-post” system, which is a racing metaphor that signifies that whichever individual, not party, has the most votes on election day, wins. There are even individuals who run that most of the party establishment wish were not on the ballot.

This model incentivizes like-minded groups to form coalitions before the election and to back a single party. If they did not do this, then, hypothetically, in a 70% right-leaning district, conservative voters could split their vote between three parties and a unified left-leaning party could sneak in with 30% (plus one) of the vote and win. That’s why in first-past-the-post systems, broad coalitions will form on the left and right until there are two main parties.

In a proportional representation party, like many parliamentary systems, these coalitions are made after, not before, the election. People will vote, not just for a person, but for a party, and the result of an election where 5% of the people vote for the Communist Party would necessitate 5% of the representative body being Communists.

But many of these smaller parties in proportional democracies tend to be single-issue or extremist. In order for the largest party to create a “ruling coalition,” they have to pull in other parties until they have a majority of the parliament, allowing them to “form a government.” This often leads to odd partnerships between groups who have directly opposing platforms.

Here in the United States, those coalitions shift too, but in less official ways. The various interests and demographics that make up a political party might realign behind the scenes as political realities change. This has happened at multiple times in U.S. history, and we appear to be in the middle of one such realignment right now.

A lot of the more isolationist and populist voters, especially ones skeptical of international wars and global trade, seem to be shifting from the Democratic Party to the Republican Party. Being passionately anti-war or against free-trade deals in the recent past would likely peg one as a Democrat, but not any more.

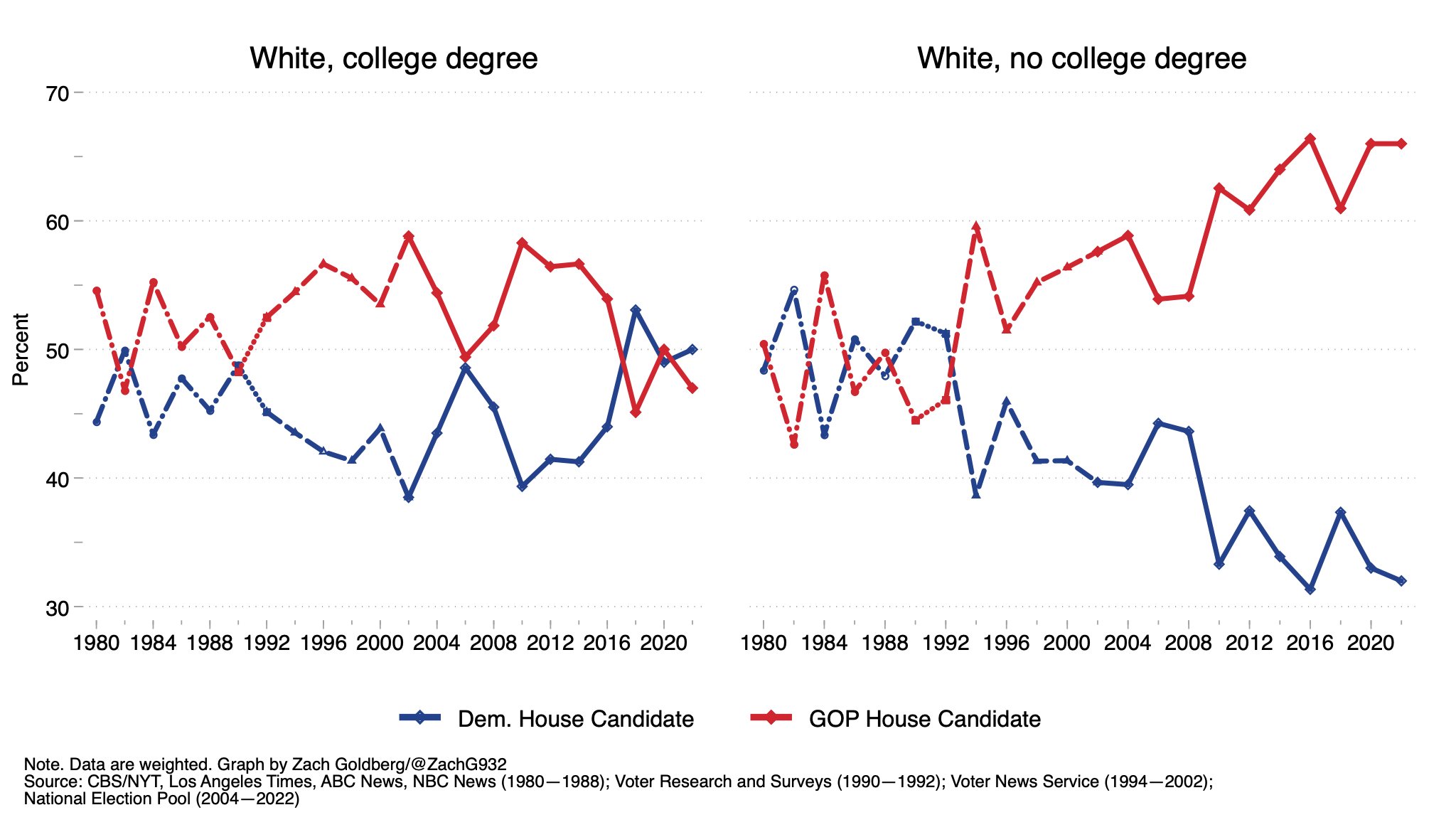

There is also a lot of evidence of demographic shifts, like of college-educated whites and non-college-educated whites swapping parties. The Republican Party, once stereotyped as the party of the wealthy elite, is increasingly shedding those voters and picking up more rural, blue-collar voters that had traditionally voted Democrat. A similar shift may be happening with Hispanic voters and even, more slowly, with black men.

Before these realignments, there are often periods where the voters choose a candidate because of who they are not because of their party. They may have to mark themselves as a moderate, a maverick, or distinguished themselves in any number of other ways.

U.S. Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia, a Democrat, has this kind of deal with his very conservative constituency, which had once been solidly Democrat but now votes overwhelmingly Republican. With a teams-based election law like S.B. 728, would legislators like Manchin be required to stop “scoring goals for the other team”? Or does this only matter if they switch parties, even if they continue voting as a maverick?

A final point to consider is that all elected officials, whether we like it or not, are unpredictable, flawed human beings. You may elect them to be a clone of Elizabeth Warren and then they end up being a swing-voting moderate who now feels more comfortable caucusing with the other party. This has happened to Republicans frequently as well.

Maybe with the rise of A.I., one day we will just elect platforms of policy positions that are then perfectly implemented without human error and whim. But until then, we’re left electing people that may or may not do what we want them to do, even if we thought they were “on our team.”