Prison is not supposed to be pleasant. It is a place for people to be punished for their crimes, hopefully rehabilitating them in the process. It is also a place where we can separate dangerous people from the rest of society. But if the state is going to justly strip offenders of their freedom, their humanity must continue to be respected.

I know; it can be hard to sympathize with inmates. Many of them committed horrific crimes. They are also out of sight and out of mind. If we hear negative news about their conditions, our instinct may be to shrug and assume they’re tough enough to handle it and (just maybe) deserve whatever happens to them.

But I don’t think the average American is aware of just what uniquely horrific places of suffering many prisons are. We likely drive by these facilities every day, not realizing they can be like little portals to hell — even down to the temperature (often facilities aren’t air conditioned) and the isolation (with long periods of solitary confinement, a practice known to be devastating to mental health).

A prison employee inside the Scotland Correctional Institution in Laurinburg recently blew the whistle to NC Newsline, describing:

“A prison so packed that people on suicide watch are sleeping in 5-by-5-foot holding cages. A disabled Vietnam veteran sent to segregation [solitary] after his peers attacked him. Incarcerated people spending months in solitary confinement, not because of misconduct inside the prison, but because they’re waiting for a bed to become available elsewhere. This is not a good situation, and until someone in Raleigh comes down and really pays attention to us, I’m afraid it’s going to get worse, and something is going to break!”

To be fair to our state’s corrections officials, they are facing an absolute crisis on staffing that makes many of these issues almost impossible to address. In data provided to Spectrum News by NC DAC, they lost 2,700 corrections officers since COVID, with their statewide vacancy rate going from 15% in April 2020 to 43% in March 2023.

The article quotes inmates saying that with prisons operating with about half the number of officers needed, violence is left unchecked, meals arrive late and cold (or not at all), and they have difficulty getting basic necessities like toilet paper.

WRAL reports that one way the corrections system is now trying to keep order is a tablets program, where smart devices are distributed to prisoners to keep them occupied.

Thankfully, there are efforts in motion to address some of these issues, especially solitary confinement and attracting sufficient staff. At a recent meeting of NC officials and prison-reform advocates, they largely agreed on the problems and the likely solutions, while acknowledging the monumental task it will be to tackle them.

At the meeting, Ardis Watkins, executive director of NC’s union for state workers (SEANC), said corrections jobs pays no better than an entry-level position at a fast-food restaurant but come with much more danger and trauma, so it’s no surprise they get left unfilled.

A former corrections officer present at the meeting said of his experience:

“Every day is an assault on your mental health when you go behind those walls. In all the years that I went behind those walls, I never got up in the morning and said, ‘I can’t wait to go to work.’ Not once, not a single day. That is one hell of a way to have a career, and I’m not alone. The mental ravages that this takes on the incarcerated population are well-known. The mental ravages it takes on staff need to be recognized and need to be dealt with.”

This is not just a North Carolina problem. In fact, we have fewer prisoners per 100,000 residents, at 340, than many other Southern states, even if it’s far above levels in other developed nations. Our conditions may be relatively better than other Southern states, as well, but that’s not saying much. Alabama, for example, was sued by Donald Trump’s Justice Department for treatment of prisoners that was “so poor that they violate the ban on cruel and unusual punishment.”

An example of the poor conditions in Alabama’s prisons from this week is the death of Daniel Williams, a 22-year-old father of two. Williams, who was serving a year for second-degree theft, was 14 days from release when a gang, taking advantage of staff inattention, decided to kidnap him and prostitute him to other inmates for money. They kept him tied up and hidden in a cell and tortured him between tricks. After guards found him unresponsive days later, they took him to a hospital, where after some time in a brain-dead state, he died.

The warden did not tell Williams’ family that he was in the hospital until three days later, telling them that he had overdosed on drugs. His step mother said it was clear from his injuries that the warden was lying to them, which an investigation later confirmed.

“And when we went to see him, he’s beaten and bruised up and you can tell where his hands were bound. I mean, you can tell it’s obviously not a drug overdose,” she said.

Homicides in jail happen at double the rate as in the United States in general, as do suicides. Even when it’s a high-profile prisoner like Jeffrey Epstein, staff shortages and negligence can provide the means and opportunity for prisoners to kill themselves or others. In Epstein’s case, the guards (one of whom was working a 24-hour shift) forged suicide-watch checks, old bed linens weren’t removed, and the cameras mostly weren’t functional.

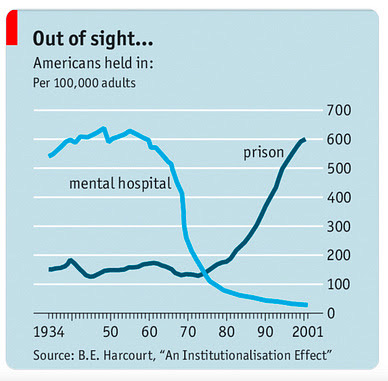

In addition to staffing issues, part of the overcrowding and inhumane conditions can be blamed on the sheer number of prisoners we are attempting to hold. While other developed countries — like Australia, Canada, and European nations — imprison between 100 and 200 people per 100,000, the United States imprisons about 360 per 100,000. As you can see in the chart from Economist Magazine below, this is a lot better than it was in the early 2000s, when over 600 people per 100,000 were locked up. These numbers came down quite a bit during and after COVID, but it’s still unusually high compared to other nations.

The chart also suggests a lot of this difference may be due to how we treat our mentally ill and drug-addicted citizens. Before closing down many mental health facilities in the 1970s, we had a very similar rate (of 100-200 inmates per 100,000 citizens) as other developed nations.

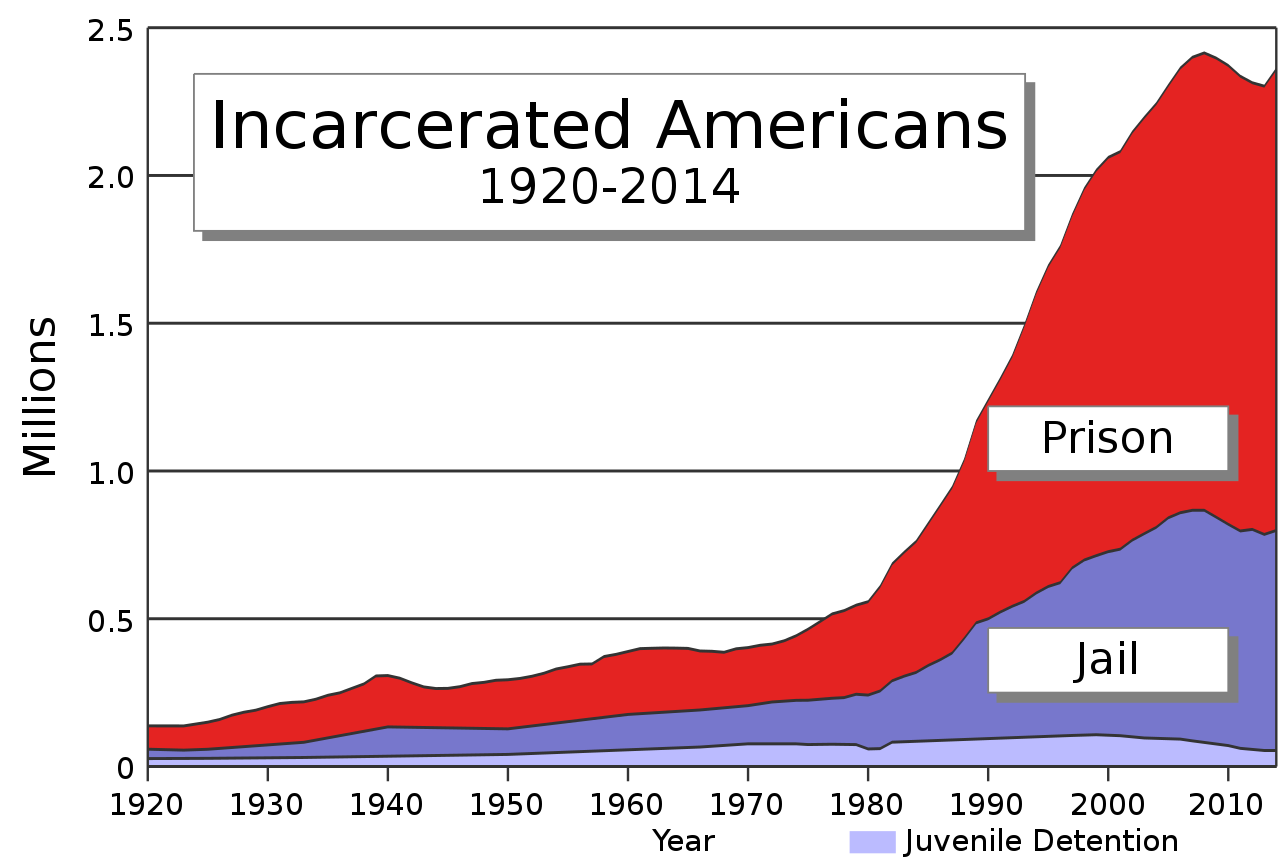

The chart below from Wikipedia shows a similar story, with a sharp spike in prison and jail populations beginning in the 1970s.

Looking at the annual cost of keeping a prisoner ($52,880 in NC) and the cost of behavioral health treatment like rehab (also about $50,000), it doesn’t appear to save us money. Favoring time behind bars over treatment likely also leads to poorer outcomes and higher re-offense rates.

NC, and the US as a whole, can surely do better. Maybe our state could even pioneer reforms, like we’ve done in many policy areas, that can be an example for other states trying to address the corrections crisis.