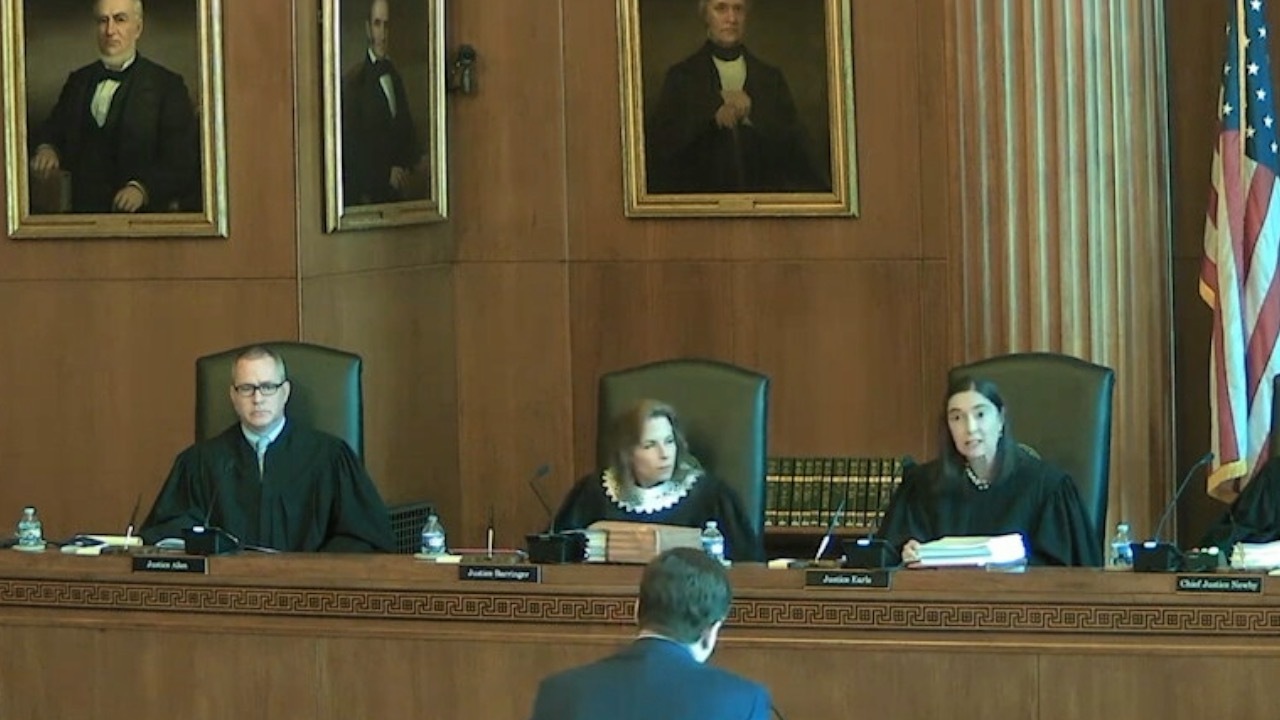

- The North Carolina Supreme Court heard 80 minutes of oral arguments Thursday in the 30-year-long education funding case commonly known as Leandro.

- State legislative leaders are asking the court to void a series of lower court orders that led to a $677 million mandate for additional state education spending.

- Plaintiffs in the case argue that lawmakers are engaging in "obfuscation" and "recalcitrance" that delay providing an adequate public education to students across the state.

The North Carolina Supreme Court could decide in the coming months whether to strike the most recent decisions about court-ordered education funding in the 30-year legal battle commonly known as Leandro.

All seven justices spent 80 minutes Thursday morning listening to and questioning lawyers who defended and opposed an April 2023 trial court order calling for $677 million in additional state funding. That order is tied to a multiyear court-endorsed “comprehensive remedial plan” that eventually could lead to $5 billion or more in new spending.

State legislative leaders are challenging the spending order. They argue that the trial Judge James Ammons lacked “subject matter jurisdiction” to call for new statewide spending. It’s one of a series of orders lawmakers ask the Supreme Court to throw out.

“This is not a contest between those who want to fund education and those who don’t,” argued lawyer Matthew Tilley, representing state Senate Leader Phil Berger, R-Rockingham, and House Speaker Tim Moore, R-Cleveland. “Instead the case is about whether the trial court, when presented with only district-specific claims, had jurisdiction to issue a sweeping statewide order — or statewide orders — that required the comprehensive remedial plan, a plan which dictates virtually every aspect of education policy and funding, not just for the districts that were plaintiffs, but for all 115 school districts across the state, effectively removing those decisions from the political and democratic process.”

Tilley argued that previous decisions in the long-running case, including a 2004 decision known as Leandro II or Hoke County I, limited the trial court’s jurisdiction to remedying problems with one school district.

Melanie Dubis, representing school board plaintiffs from Hoke and four other counties, criticized lawmakers’ arguments.

“At best, they reveal a fundamental misunderstanding of the history and present reality of this litigation,” Dubis said. “At worst, they suggest a desire for further obfuscation and recalcitrance in lieu of remedying this decades-old constitutional violation. … They seek to drag the court into their gamesmanship.”

Dubis’ plaintiffs worked with lawyers from the state’s executive branch on the Leandro plan, which was based on a report developed by a San Francisco-based consultant called WestEd.

State Solicitor General Ryan Park, representing the executive branch, defended earlier Leandro-related decisions as “shining lights” in the state Supreme Court’s history.

The court’s two Democratic justices focused most of their questions on challenging Tilley’s arguments.

Justice Anita Earls focused on a portion of the 2004 decision.

“Where the state is saying to the plaintiffs, ‘We can’t solve your individual county problem because we have a constitutional mandate to provide equal educational opportunities to all students across the state,’ where the state takes the position, ‘We can’t just give you a remedy, Hoke County, we have to remedy the problem statewide,’ are you suggesting we also have to overturn what we said in 2004?” Earls asked Tilley.

Justice Allison Riggs questioned the idea that the court must limit its ruling to students in one county.

“Even if every single one of the 115 [local education agencies] are represented by parents or children, there is never going to be a situation where this court can say — because there are failures to provide a sound basic education — there’s never going to be a situation based on your theory of subject matter jurisdiction where we can force … tell the state you have to appropriate money to solve this problem, even if the trial court finds that lack of funding is what is leading to these Leandro violations,” Riggs said.

Three of the five Republican justices spoke during the hearing.

Justice Trey Allen asked both Tilley and Dubis to confirm that no current students are plaintiffs in the case that dates back to 1994.

“We made it crystal clear in Hoke [the 2004 case] that the right for an opportunity to a sound basic education is one that students possess and not school boards,” Allen said. “If there are no students left in the case, doesn’t that mean we have no parties left in the case that are entitled to relief?”

Justice Richard Dietz also questioned Dubis about her school board clients, as agents of government, standing in for the people whose constitutional rights are at stake.

“I’m thinking about the students,” Dietz said. “This case needs to get to the outcome, which is to cure a very serious violation of the constitutional rights of students in our state. But one thing that’s awkward is that your client is the government. And it’s not just the government, but it’s the very government that’s violating the children’s constitutional rights.”

Dietz also questioned whether accepting the comprehensive remedial plan would shut the door on future lawsuits making Leandro-related claims.

“I’m just concerned that there are students that are out there who may say, ‘Wait a minute. That’s not fair that the government is the one that’s deciding this for me. I never got to come to court and say here’s how you fix my school,’” Dietz explained.

Justice Phil Berger Jr. cited High v. Pearce, a 1941 state Supreme Court precedent. “This court said where there is no jurisdiction of the subject matter, the whole proceeding is void ab initio and may be treated as a nullity anywhere at any time for any purpose,” he said.

A proceeding that is “void ab initio” is invalid from the start.

Both Berger and Earls took part in Thursday’s hearing despite requests that they recuse themselves. Earls once represented one of the parties in the dispute. Berger is the son of the state Senate leader. Earls rejected recusal unilaterally. The court voted, 4-2, to allow Berger to take part in the case.

The state Supreme Court’s latest consideration of the education funding case results from an appeal from top legislators.

While many people refer to the case as Leandro, the name of the original lead plaintiff in the 1994 lawsuit, lawmakers and Republican Supreme Court justices label the case “Hoke County.” A November 2022 decision from the state’s highest court is known either as Leandro IV or Hoke County III.

The state Supreme Court voted 5-2 in October to take another look at the case. That decision split the court along party lines. Republicans agreed to grant another review. Democrats dissented.

Earls explained in a dissent why she and Riggs would have rejected lawmakers’ request.

“Legislative-Intervenors’ bypass petition should be denied because it is substantively hollow and procedurally improper. This Court resolved the question of subject-matter jurisdiction in Leandro IV,” Earls wrote. “In that case — just 11 months old — the Legislative-Intervenors raised the same arguments they do in their bypass petition: That the trial court lacked jurisdiction to remedy constitutional deficiencies in public education. We examined that claim and ‘unequivocally rejected’ it.”

Earls rejected state lawmakers’ arguments that the case should focus only on Hoke County schools.

“Since the trial court found a statewide constitutional violation, we explained, it had subject-matter jurisdiction to order a statewide remedy,” she wrote. “But the Legisative-Intervenors ignored the trial court’s sound analysis and solid conclusion. They instead argued before us — as they do now in their petition — that ‘there has never been a finding’ of a constitutional violation ‘beyond Hoke County.’ We rebuffed that argument. And we went further, decrying it as ‘a fundamental misunderstanding of the history of this case and the State’s constitutional obligations.’”

“If parties can reopen a case by casting their disagreement in the language of ‘jurisdiction,’ then our courts will be nothing but revolving doors and our decisions nothing but paper tigers,” Earls wrote. “This case shows the danger of that approach.”

“We already grappled with and resolved the question of subject matter jurisdiction in this case — nothing imperils that decision or requires us to revisit it,” she added. “But by alchemizing its disagreement with Leandro IV into a ‘jurisdictional’ issue, the majority gives itself a tool to rewrite — and litigants to resist — our earlier decisions.”

A concurrence from Berger, joined by Dietz and Allen, answered Earls’ critique.

“The premise of the dissent is that this Court already ‘resolved the question of subject-matter jurisdiction in [Hoke County III].’ The dissent is wrong,” Berger wrote.

Berger noted Earls’ earlier work as a lawyer helping plaintiffs add the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools to the long-running case. The legal dispute had started with five different school systems.

“Core to their rationale for intervention was that every public school district faces its own unique educational challenges and groups of students or school districts in one area of our state are ill-suited to address the educational deficiencies in others,” he wrote.

“This raises questions that our Court has not yet addressed: If public school students or local school boards who are not parties to this case believe the remedial order does not sufficiently address the educational failure in their districts, are they bound by the remedial order?” Berger added. “If so, how were their rights adjudicated without their presence in the suit — an elementary principle of jurisdictional law.”

Berger wrote that Earls and the previous Supreme Court majority “rushed to complete its earlier opinion in this incredibly complex, novel case (one that has spanned decades) so that it could be released in November of last year. The failure to resolve these jurisdictional questions is not the first oversight from this Court’s rush to judgment in Hoke County III.”

“My dissenting colleague laments that subject matter is now being addressed because it will cause various harms to judicial integrity and ‘snuff out legal finality,’” Berger said of Earls. “Once again, we endure ad nauseum these fanciful protestations. But it is black letter law that courts cannot ignore potential defects in subject matter jurisdiction.”

“Even if we again failed to address jurisdictional concerns, these issues could be raised later in a collateral attack on the trial court’s order, causing tremendous chaos if steps are already being taken to execute the novel relief in the remedial order,” Berger warned.

“In its rush to publish an opinion in the prior matter, the majority declined to address fundamental subject matter jurisdiction questions,” Berger concluded. “To be sure, these issues were raised, but the majority chose to ignore the bedrock legal principle that courts must examine jurisdiction to act. Even legal neophytes understand that subject matter jurisdiction can never be waived and can be raised at any time.”

“Because these crucial issues of subject matter jurisdiction cannot be waived and must be addressed by this Court, it is a sound exercise of this Court’s constitutional role to take this case and permit the parties to brief the various issues.”

There is no deadline for a decision in the case, which is likely to be known as Leandro V or Hoke County IV.