- The North Carolina State Supreme Court will decide in the months ahead whether Greenville's red light camera enforcement program was unconstitutional.

- The state's second-highest court ruled against the Greenville program's funding mechanism in March 2022.

- Critics argue that the system did not send enough money to Pitt County schools. The city and school board argued that the General Assembly authorized their cost-sharing agreement.

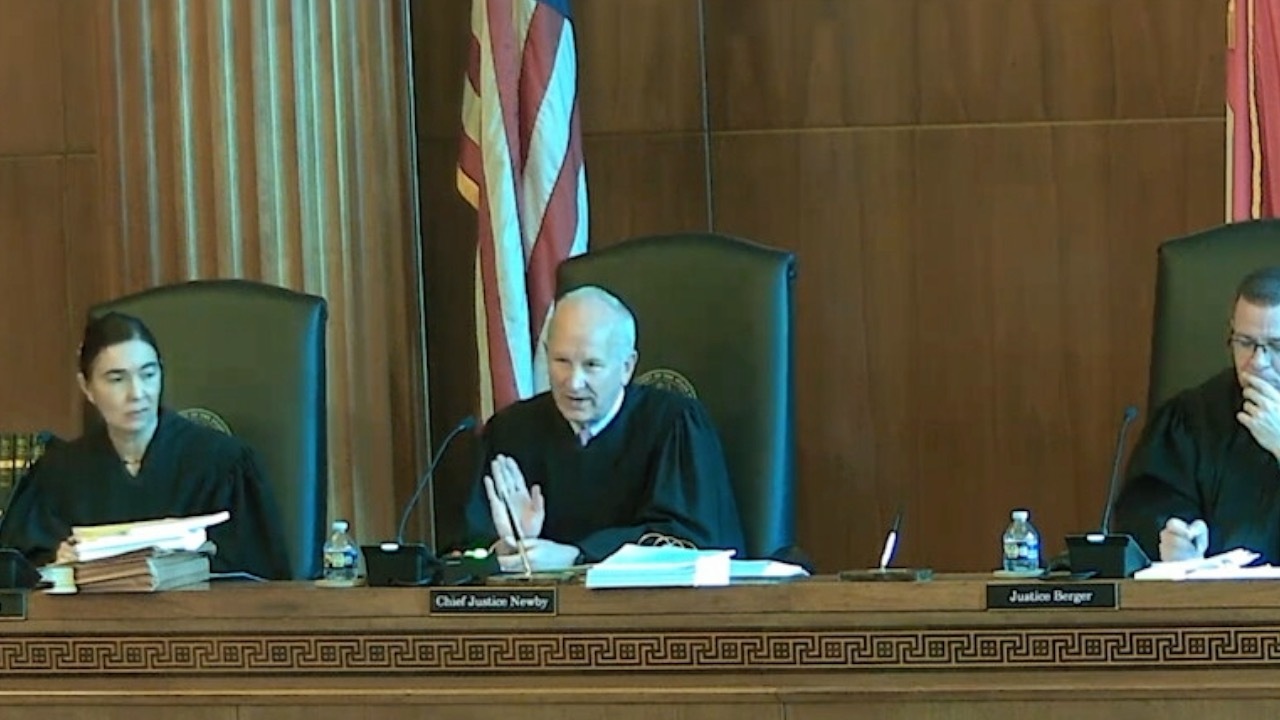

The North Carolina Supreme Court will decide in the months ahead whether a cost-sharing agreement that funded Greenville’s red light camera enforcement program complied with the state constitution. Justices heard an hour of oral arguments on the topic Wednesday.

Greenville shut down the red light camera program in November 2022, eight months after the state Court of Appeals ruled the program unconstitutional. Appellate judges determined that Pitt County schools did not keep enough money from the proceeds of red light camera citations.

The Appeals Court ruling could have led to refunds for red light camera violators.

Lawyers defending the program highlighted for Supreme Court justices the General Assembly’s 2016 law granting Greenville and Pitt County the right to enter into an agreement for funding red light camera enforcement.

“That agreement is … There is no question really that it is to the mutual benefit of the city and the Board of Education,” said Dan Hartzog, Greenville’s lawyer. “The city achieves its purpose of increasing safety, increasing efficiency, and operating the red light cameras. The Pitt County Board of Education, over the brief course of the program, which is not currently running due to this litigation, got roughly $2.5 million in revenue that they would not otherwise have received.”

Appellate judges agreed with the plaintiffs in the case, Fearrington v. City of Greenville, that the cost-sharing agreement fell short of a standard spelled out in Article IX, Section 7 of the state constitution. It gives the “clear proceeds” of fines and penalties to local schools. Previous court cases have determined that “clear proceeds” must be at least 90% of the funds, according to the appellate decision. Pitt County schools kept about 72% of Greenville’s red light camera money.

“If this court were to uphold the Court of Appeals opinion, the Pitt County Board of Education would have less money as a result,” Hartzog said. “That is a perversion of what the fines and forfeitures clause is intended to do.”

The school board’s lawyer criticized the plaintiffs’ motives. “Plaintiffs are not here to help the schools,” Robert King argued. “Their goal in filing this lawsuit is to shut down the red light camera program. If they can’t put some money in their own pockets, they will do that.”

“They want to take Article IX, Section 7, turn it into a weapon, and take money away from the schools and put it in the pockets of people that broke the law and endangered the public,” King added. He labeled the constitutional argument “as twisted a use as you could possibly get.”

The plaintiffs’ lawyers argued that the funding arrangement calls for Pitt County schools to fund costs banned by previous court decisions. “There is no doubt that the school system of Pitt County is paying the enforcement costs,” argued Paul “Skip” Stam. “You’ll see through these schemes, I believe.”

Stam also questioned Greenville’s role in funding the red light cameras. “The city of Greenville is not willing to put money into it at all,” he argued. “You would think that if Greenville was interested in public safety, they would be willing to spend a little money on it.”

Stam is a member of the board of directors of the John Locke Foundation, which oversees Carolina Journal.

Justices asked why money should be refunded to people with red light camera citations, rather than sent to the local schools.

“We’ve said appropriating public funds to an Arizona corporation to run red light cameras violates Article IX, Section 7 of the state constitution,” argued attorney Dan Gibson. “You can’t do that. That’s illegal. We want an injunction preventing you from spending that money.We’s like our money back because you took our money fraudulently, ultra vires, unconstitutionally — whatever label you want to put on that.”

“If the constitution doesn’t grant you the authority to do it, you never had the authority to take our money, and it’s still our money,” Gibson added.

Justice Richard Dietz is recused from the case since he was one of the appellate judges who ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in 2022.

Each of the other six justices asked questions during the arguments. They asked how precedent cases should affect the ruling and whether the General Assembly’s 2016 law should benefit from the “presumption of constitutionality.” Chief Justice Paul Newby asked how a ruling for or against Greenville’s program could affect red light camera enforcement in other cities.

Hartzog promoted Greenville’s program as a “model for how it should be run.” “The question is: Does a system in which they get $2.5 million over a couple of years advance public education? Does that help maintain free public schools? It would be absurd to say that it doesn’t,” he argued.

The state Supreme Court blocked the initial Appeals Court ruling in 2022. Roughly a year later, in April 2023, the high court agreed to take the case.

“Education is a constitutional right imperative to the well-being of the children of North Carolina and the state itself. North Carolina guarantees ‘[t]he people have a right to the privilege of education, and it is the duty of the State to guard and maintain that right,’” wrote Jeanette Doran, NCICL president and general counsel, in a friend-of-the-court brief filed I August.

“To help guard and maintain this right, N.C. Const. Art. IX, § 7, ‘The Fines and Forfeitures Clause,’ mandates that the ‘clear proceeds’ of all fines, penalties, and forfeitures ‘for any breach of the penal laws of the State, shall belong to and remain in the several counties, and shall be faithfully appropriated and used exclusively for maintaining free public schools,’” Doran added.

The NCICL brief challenged the constitutionality of an agreement between Greenville and Pitt County Schools about sharing red-light proceeds.

“A ruling affirming the Court of Appeals’ entry of summary judgment in favor of Plaintiffs’ Article IX, § 7 claim is essential in safeguarding public education and the constitutional framework for its funding,” Doran wrote. “Defendants have entered a Red-Light Camera Enforcement Program interlocal funding agreement that circumvents public school funding requirements established by the People in their Constitution.”

Greenville and the school district “invite an interpretation of Article IX, § 7 that cannot be reconciled with constitutional text and that would render the Fines and Forfeitures Clause impotent,” Doran argued. “Because the Board receives less than the clear proceeds of civil penalties collected by the City’s RLCEP, the RLCEP violates The Fines and Forfeitures Clause, and this Court should so hold.”

An ACLU friend-of-the-court brief argued against “profit-driven law enforcement.” The group contends policing linked to profits “undermines public safety,” in addition to being regressive, extractive, and a bad way to fund public services.”

“Simply put, the laudable goal of directing resources towards North Carolina’s public schools does not justify governmental reliance on regressive law enforcement schemes like the one at issue here,” ACLU’s lawyers wrote.

Pitt schools netted about 72% of the proceeds from Greenville’s red-light camera citations. A unanimous three-judge appellate panel ruled that the schools’ share from red-light camera enforcement would need to top 90% to meet state constitutional standards.

“[W]e hold that the funding framework of the RLCEP violates the Fines and Forfeitures Clause contained in Article IX, Section 7 of our State Constitution,” wrote Judge Jefferson Griffin.

Greenville’s Supreme Court brief disputed the Appeals Court’s reasoning. “This holding was in error, as the panel misconstrued and improperly invalidated the City and the Board’s independent and legislatively authorized cost-sharing arrangement,” wrote the city’s lawyers.

State lawmakers endorsed the funding arrangement between Greenville and the Pitt school board, according to the city’s brief. “The Interlocal Agreement is also specifically authorized by the General Assembly through S.L 2016-64, which provides that the Interlocal Agreement ‘may include provisions on cost-sharing and reimbursement that the Pitt County Board of Education and the City of Greenville freely and voluntarily agree to for the purpose of effectuating the provisions of G.S. 160A-300.1 and this Act.’”

The requirement that local schools receive “clear proceeds” from red-light citations doesn’t equate to a 90% share, Greenville’s lawyers argued. “The term ‘clear proceeds’ does not mean all monies collected from a civil penalty,” according to the brief. “Rather, it means net proceeds, that is, the proceeds left after the cost of collection are deducted.”

In a separate brief, the Pitt County Board of Education also defended the funding arrangement. Pitt school leaders rejected legal arguments from plaintiffs who challenge the red-light camera program.

“In every Article IX, Section 7 case this Court has decided before today, the injured party (i.e., the entity that ultimately is going to benefit from enforcing the Fines and Forfeitures Clause) is the public schools. But Plaintiffs seek to convert this protection instituted by the framers of our Constitution into a benefit for themselves,” the Pitt school board’s lawyers wrote.

“Their argument – that the Board may not voluntarily enter an inter-local agreement that increases revenue for the Board – would twist the meaning of the Fines and Forfeitures Clause from one that protects resources for schools into one that restricts the ability of local governments to increase school funds,” according to the brief. “And, as Plaintiffs further argue, if the local governments fail to comply with these restrictions on their ability to raise funds, the result is that the funds must be returned to those who paid them.”

“Nothing could be further from what the Fines and Forfeitures Clause plainly says or what the Framers of the North Carolina Constitution intended.”

There is no deadline for a state Supreme Court decision.